Table of Contents

Jeffrey Lindsay

Jeffrey Dean Lindsay is a US patent agent, technology scout, and intellectual property (IP) strategist using IP to help client cope with the challenges of disruptive innovation. He has a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Brigham Young University.

One of the great paradoxes of China is how a Communist nation became so prosperous by unleashing a wave of economic liberty shortly after the painful era of the Cultural Revolution. The rarely told story of China’s economic rise begins with a small group of starving farmers in the village of Xiaogang who put their lives at risk by defying collectivism. The story of their success demands our attention today.

I visited China in 1987 and saw a nation beginning to rise out of poverty. In 2011 while interviewing for a job that I accepted in Shanghai, I was stunned at how much China had changed. Exotic skyscrapers arose where flat buildings once stood. Signs of wealth abounded. What brought so much prosperity? When my wife and I moved to Shanghai, we were surprised at just how free and vibrant the nation seemed.

Another surprise was the rapid growth of China’s patent system. Intellectual property has been flourishing in China, motivating millions to invent and create new businesses. In 2019, China became the world’s top filer of international patent applications. They didn’t even have an IP system until 1984 – how could they go from nothing to leading the world in just a few years? In industry after industry, China is taking a leadership position in technology and IP that can’t be won by copying.

How did this happen? Part of the answer begins with a few farmers in Xiaogang (pronounced like “shao gong”) village in Anhui Province.

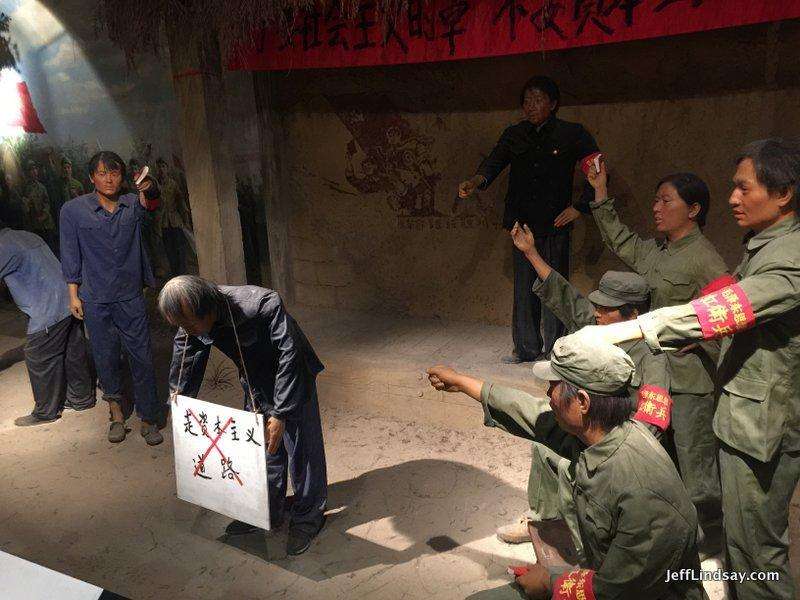

I first learned of Xiaogang from Michael Meyer’s In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China. In the 1950s, perhaps 40 million died of starvation during the “Great Famine.” Under collectivism, the farmers’ crops were essentially confiscated, forcing them to live off rations. There was no incentive to produce. Hard work made one hungrier. Abuses by those redistributing wealth compounded economic woes.

Meyer also describes a secret scheme forged in the embers of desperation in tiny Xiaogang, where my wife and I made a pilgrimage in 2017.

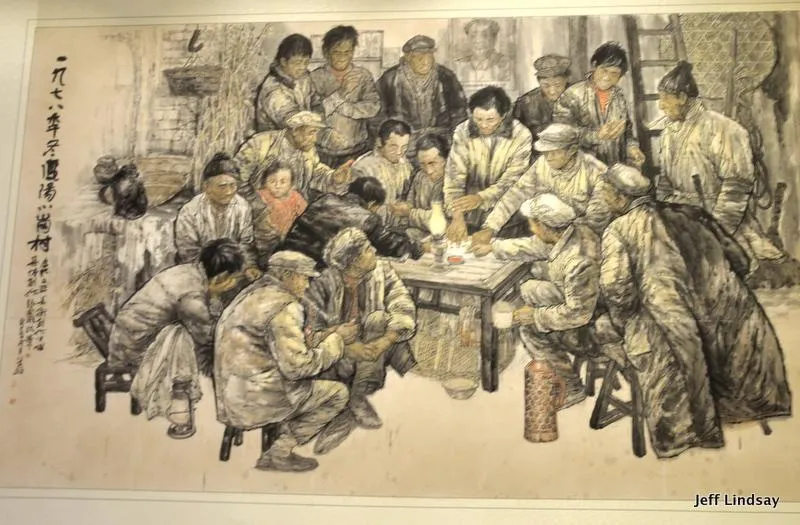

In 1978, shortly after Mao’s death, China was still reeling from his Cultural Revolution. Collectivism was a disaster. Over half of the 120 villagers in Xiaogang had died of starvation. They were starving again.

One man, Yan Hongchang, a 29-year-old father and deputy leader of the village work team, decided to make a daring change. On November 24, the heads of eighteen families gathered secretly and signed a pledge to divide the commune’s land into family plots, give a quota of their corn to the government, and keep the rest for themselves. There was obvious danger.

“In the case of failure,” the document concluded “we are prepared for death or prison, and other commune members vow to raise our children until they are eighteen years old.”

The farmers signed the document and affixed their fingerprints. Thus began China’s rural reform.

Today a large stone monument to the pact greets tourists to the village. But in the spring of 1979, a local official who learned of the clandestine agreement fumed that the group had “dug up the cornerstone of socialism” and threatened severe punishment. Thinking he was bound for a labor camp, Mr. Yan rose before dawn, reminded his wife that their fellow villagers had promised to help raise their children, and walked to the office of the county’s party secretary. But the man privately admitted to Mr. Yan that since the pact had been signed, the village’s winter harvest had increased sixfold. The official told Mr. Yan he would protect Xiaogang village and the rebellious farmers so long as their experiment didn’t spread.

In the coming days, other villagers saw something unusual was happening. The secret was not easy to keep. The system spread from village to village, quickly leading to a 600 per cent increase in regional production. China’s new leader, Deng Xiaoping, looking to help China recover, investigated the unusual results. Rather than being punished, Yan would be recognized as the hero who inspired Deng Xiaoping.

Deng had to overcome political obstacles, but saw the economic potential of the Xiaogang “innovation.” Deng formalized the Household Contract Responsibility System, or da baogan, allowing families to farm their own allocation of land. They had to give a portion to the state, but the rest they could eat or sell at unregulated prices. Agricultural taxes were abolished in 2006. For details on the many changes, see “Disbanding Collective Agriculture” in Jonathan Unger’s The Transformation of Rural China and an interview with Yan Hongchang.

Deng went and opened economic doors in Shanghai, Guandong, and Shenzhen, allowing citizens to reap the rewards of their work. Success there inspired broader reforms.

What is proudly called “socialism with Chinese characteristics” for many years has resembled economic freedom with various property rights. (Political freedom in China is a different story, of course.)

Xi Jinping visited Xiaogang in 2016 and declared, “The daring feat we did at the risk of our lives in those days has become a thunder arousing China’s reform, and a symbol of China’s reform.”

A tourist centre and a large commemorative museum shows officials expected the village to become a major attraction. But since Xi’s visit in 2016, it has received little attention, perhaps because the story clashes with today’s emphasis on Marxist-Leninist doctrine.

When we arrived in 2017, there were no buses or crowds. We were the only visitors in the museum. It was politically correct, blaming weather for famine and praising party leaders, but still noted opposition of the hard-Left to reform. We had to leave abruptly because it was lunch time, but were told we could visit a site about 200 meters away. Fortuitously, that was the easily-overlooked home of Yan Hongchang.

The workers at Yan’s home were locals proud of their history. They showed us the room where the contract was signed and an extension of the home added as the farmers prospered. A sewing machine and television were signs of stunning prosperity. Xi’s praise was on a large sign. That home was the main attraction, the epicentre of China’s thunderous rise.

The story behind China’s recovery from collectivism is one to celebrate. The skyscrapers of Shanghai, Beijing, and many other cities are testaments to the success that economic liberty can bring. May we not forget the millions who perished under collectivism, and may we celebrate the courageous few who brought an “innovation” that lifted China from poverty and famine.

Jeffrey Lindsay

Jeffrey Dean Lindsay is a US patent agent, technology scout, and intellectual property (IP) strategist using IP to help client cope with the challenges of disruptive innovation. He has a Ph.D. in chemical engineering from Brigham Young University.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.