Table of Contents

We all know that the legacy media are shameless liars. We also know that ‘fact checkers’ are in truth anything but. What ‘fact-checkers’ really are is confirmation bias machines, riddled with institutional bias (even the Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review admits that 80 per cent of its ‘experts’ are left-wing, and more than half of them “very left-wing” by their own admission).

But that doesn’t mean that anyone and everyone who isn’t the legacy media must therefore be rigorously truthful. Sometimes a nutty conspiracy theory really is just a loony conspiracy theory. Too often, independent media figures are just as shamelessly biased liars as their legacy counterparts. Just because the government and public health bureaucrats knowingly lied about Covid-19 doesn’t mean that that whacker with the YouTube channel is a reliable source of information.

To try and help you cut through the fog of genuine misinformation, I’ll be publishing more of my How Not to Be Fooled columns, but, in the meantime, Bellingcat have also provided a helpful guide in trying to verify anything you may read or see online.

Verification doesn’t need to be difficult. It also doesn’t require any complicated algorithms or access to advanced tools or programs that automatically detect whether an image may be fake or manipulated.

A critical mindset and a close look at the context of an image or post, allied with simple tools such as a Google search or reverse image platforms, are often all it takes to discover whether a piece of content is genuine.

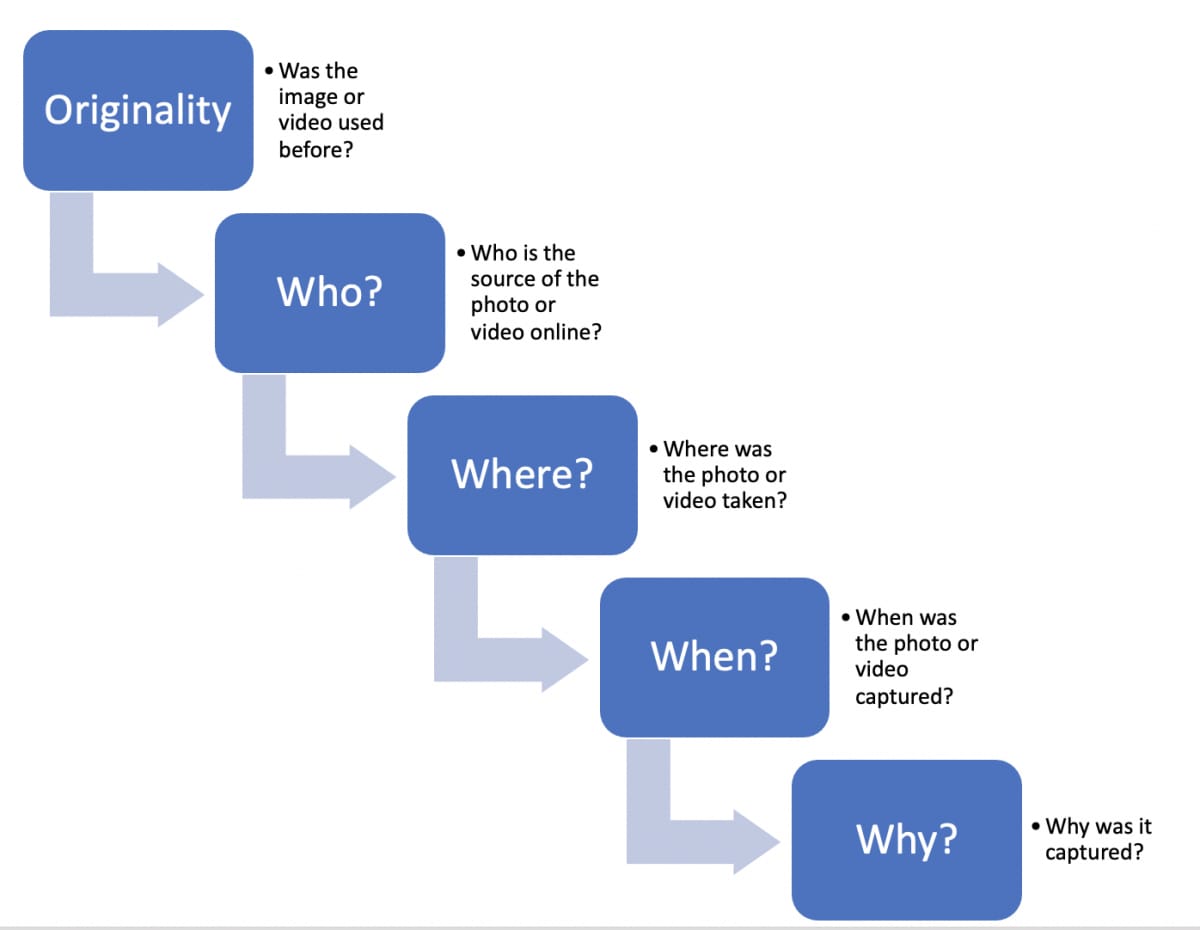

Let’s start with some basic fact-checking principles to look for.

1. Originality

During most high profile news incidents, a number of photographs and videos will appear online. Amongst these are likely to be misleading, recycled images and sometimes even outright fakes. It is therefore important to ascertain the originality of the media shared. For example, has a picture been repurposed or used before? Reverse image search platforms, which we will discuss later, are extremely simple to use and can quickly help uncover previous uses of an image online.

2. Who is the source of the photo or video online?

Now, it is true that there is the genetic logical fallacy: disregarding a piece of information simply on the basis of the source. That said, though, some sources simply are more trustworthy than others. If the source is a site with poor standards, then turn your bullshit-detectors correspondingly higher. Try to find separate, higher-quality sources. If the seemingly low-quality source is reproducing other, linked, material, follow the links.

3. Where was the photo or video taken?

If it can be proven that an event took place at a location separate to that claimed in a video, there is a good chance we can verify the information it contains is false.

A famous example is a major media company posting a video alleging to be war footage, which was in fact a fireworks display in the US.

Similar to where is when.

4. When was the photo or video captured?

Once a location has been established, chronolocation helps us to determine the time an event happened. If it can be proven that a video or image was taken at a time long before or after that which is claimed in a post, there is a good chance we can verify its claims as false.

A guide to both geo- and chrono-location can be found here.

5. Why was it captured?

People post media online for all kinds of reasons. Some may be genuine but others may be doing so to further a political or personal viewpoint. It is important to understand the motivation behind posts. For example, if a post has been made by someone who has a history of posting about misinformation, conspiracies or from a heavily biased viewpoint, it is wise to exercise caution and carry out further checks as to the veracity of what they are posting.

A working example of the above principles occurred during a famous incident where a container ship ran aground, blocking the Suez Canal. In the flurry of genuine and fake news that surrounded the incident, the QAnon conspiracists pounced on a video showing a container they claimed was being used to traffic children.

Except there was no evidence for that claim at all or that the container was even on the ship in question.

As it happened, the video had a TikTok logo with a username. Following those breadcrumbs, it turned out that the video originated on an account related to different types of mining machinery and equipment.

Further clues can be found in the content of the video itself. The video shows a person walking towards and opening a container. Inside are chairs and other objects. “MineARC” is written on the door with an accompanying logo. The words “refuge chamber” can also be seen, as can the term “mineSAFE” […]

It quickly becomes apparent that MineARC manufactures chambers that are likely a match for the container in the Tik Tok video, with a number of items appearing identical to what is visible in product pictures on the MineARC site […]

This allows us to say with confidence that there is no evidence that the video shows anything to do with child trafficking.

In other cases, such as videos purporting to show a particular incident, screengrabbing a shot from the video and uploading it to a reverse-image search tool, such as Google Images, Bing Images, Yandex or TinEye, can quickly show if the video is in fact of something else entirely.

Also look for signs of image alteration and manipulation. In one notorious example, a photo purporting to show a city being heavily bombed was obviously subjected to heavy cloning of a single column of smoke. In another example, in the furore surrounding George Floyd’s death by overdose, some circulated an image comparison that claimed to ‘prove’ that police officer Derek Chauvin was innocent, because the ears visible in his mugshot appeared to differ from those seen in the video shot at the scene of Floyd’s death.

Note, though, the patch on Chauvin’s shoulder: the word ‘Minneapolis’ is clearly reversed.

That being the case, we can now be certain that it is Chauvin’s right ear depicted in the mirrored image and his left ear in the mug shots. On top of this, the quality of the mirrored image is significantly poorer than the mug shot. Even if it was the correct ear, any comparison by the human eye alone would have been difficult.

At the very least, the fact that the image has been manipulated should be a red flag that the claim should be treated with extreme caution and is highly unlikely to be true.

To summarise, here’s a handy checklist of things you should bear in mind when trying to verify information: