Table of Contents

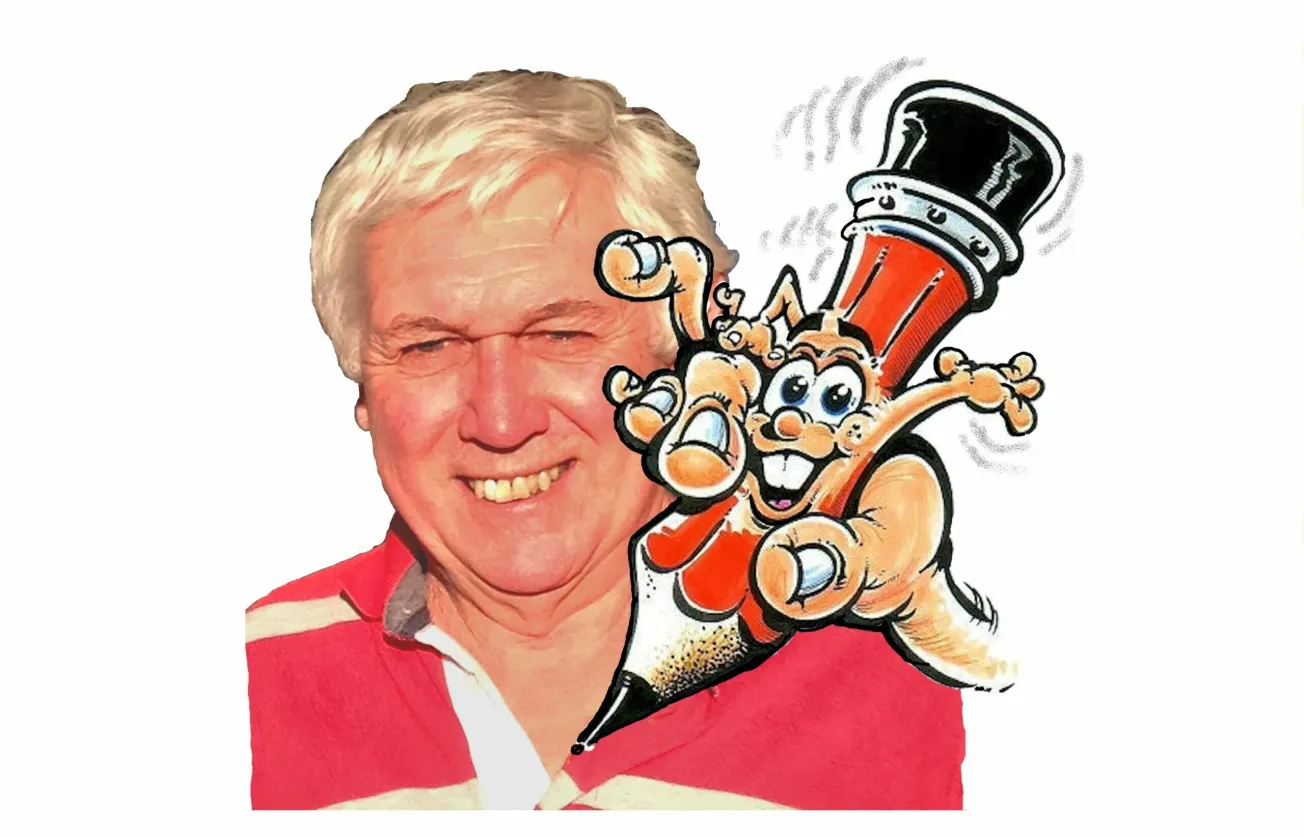

Brian Doyle

Brian Doyle draws cartoons for MercatorNet. He lives in Brisbane, Australia.

Have you always been a cartoonist?

The moment I picked up a pencil over 70 years ago I was hooked. Dad was a journalist who brought home the old Aussie Bulletin every week to show me the cartoons, which of course I didn’t understand, but I loved the funny way they were drawn.

About age six he gave me a book of cartoons drawn during the war by English cartoonist David Langdon. I spent hours trying to copy them. Then came the comic books. I lost all interest in drawing ‘properly’’ and have only ever drawn cartoon-style since.

I was totally obsessed with cars and at 18 published the first of many magazines of Hot Rod cartoons. My first job was in Woolworths Brisbane advertising department, later moving to an advertising agency: its main account was Coles Supermarkets. I also created ads for other clients by designing a sensible ad, then a fun cartoon ad that often made my very stern boss laugh … before chucking them into the rubbish bin!

One lucky day a client, a Ford dealer, was grumbling that our ads for his used cars weren’t working. I couldn’t help opening my big mouth and suggested we draw recognisable cartoons of Holdens, VWs, Morrises, Zephyrs and Austins instead of using photographs.

Just as I was preparing to be fired, the client agreed. The very first cartoon ad got record sales, much to my relief, and few more clients followed. Later Coles asked me to become their state advertising manager and set up their own advertising department.

So, so, so booooring for six tedious months. Finally, I bit the bullet, resigned and set up a small art studio specialising in cartooning for advertising agencies, printers, publishers, corporations, businesses and government departments… or anybody!

Then I stumbled into unexpected opportunities for cartooning — illustrating books and educational material for children in schools, on career options for secondary education and training, working with children with physical and mental disabilities, severe autism, self-harming and suicide prevention, even with teens who’d been expelled from ordinary schools for criminal activity like attacking teachers with knives and other weapons in a special ‘locked door’’ school, where I quickly discovered the real communication power of the cartoon.

All children love to draw, but around seven or eight they figure they can’t draw ‘properly’ and throw their pencils away forever. So I created a school classroom Cartoon Funshop session to teach them how to draw ‘unproperly’ instead, learning my simple professional cartoon drawing tips, clues and shortcuts by following my drawings on a whiteboard.

With a small start-up grant from the Queensland Arts minister in 2001, I visited hundreds of schools, libraries and galleries from the Gulf up north, as far west as Birdsville and south of Sydney teaching almost a quarter of a million kids how to simply draw for fun. It’s an erratic life, but it’s been interesting, just trying to do what I thought I was fairly good at, something I’ve said to encourage so many, many children.

How do you get ideas?

I wish I knew.

In my school Cartoon Funshop sessions, I’d point out the window and imagine we saw 50 kids running across the playground. I’d ask the class “Where do you think they’re running to?” Lots of suggestions, but then I ask: “What do you think they’re running away from?” I always look in the opposite direction from what appears to be happening, that’s often where the truth lies. I find it a great idea starter.

I used to tell kids to imagine you could open the top of your head, like a lid. Then remove your Sensible Brain and replace it with your Silly Brain. Then ask it silly questions, listen only to silly answers and draw them.”

Fortunately, after many years of practice, one or two cartoon ideas on a given subject or event often drop off the end of my pencil, or a visual image pops into my head, or I’ll be looking at something totally unrelated and think: “Hey, I can adapt that, it’s sorta like what I’m looking for.”

When trying to create a weekly cartoon for MercatorNet, I have developed a broad system. The main thing to remember is that it’s not all about me, I’m the third cab off the rank, after the writer and the editor. After I read the article, I crank up the Silly Brain. First I read it over and over asking myself one question only. “What is the main message the writer wants to convey to his readers?”

The cartoonist has seven basic tools in the toolbox, or perhaps weapons in the arsenal, depending on the content and tone of any issue. Obviously humour comes first, followed by exaggeration, irony, stereotyping, analogy, labelling (when desperate, but a bit out of fashion) and the most difficult of all, caricature.

I love to twist, warp and turn thoughts and images inside out, upside down until a workable idea comes out of… who knows where? That’s about all I can say, except that it might simply be a rather enjoyable degenerative brain disease that makes you see the world in a tangle of twisted lines.

Cartoons are unfair… justify your existence!

Fair enough! Any cartoonist who wants to be ‘liked’ on Facebook ought to surrender his pencil. Nothing gives me more pleasure than to get intelligent criticism. It proves that my cartoon caused somebody to think and they care enough to fight back. As the old saying goes, “I disapprove of what you say, but will defend to the death your right to say it.” How unwoke is that?

Freedom of thought and speech have never been under such fanatical attack as they are in the Western World today. We are being ‘corrected’ back into the dark middle ages of mysticism, fantasy and ignorant tribal groupthink. The thing political pushers of hate fear most is being laughed at. They simply lack a sense of humour.

I do try to keep the degree of visual savagery in direct proportion to the degree of political idiocy displayed by the perpetrator. But that seems to be getting harder as I get older and the world gets woker and broker.

Have computers changed how you work?

Have they ever! When I first started in the advertising industry, we were still using the same basic mechanical printing process Gutenberg invented in 1440.

After I opened my cartoon studio in the early ’80s I had to visit clients for a briefing on every job, which often took hours while they attended to constant phone interruptions, coffee breaks and distractions. I would return to the studio, design a rough concept for the project, jump back into the car, revisit the client, note any alterations, drive back to the studio, make the amendments, get in the car… and so on. Then this wonderful new device, the fax machine. Then the bulky desktop computer.

Lenore managed a childcare centre at the time and had to learn how to use one. I was amazed by her skill and she kept saying I needed one, but its complexity terrified me. She finally insisted and we shelled out for a Dell. Wow! I could now get a brief from a client by email, draw a rough design, scan it and email it back so they could make any amendments, email them to me… etc.

This process increased my productivity enormously. A job that took weeks could now be done in days. But I still had to colour my cartoons by hand using pencils, markers, inks and brushes.

Then everything changed drastically. I discovered a Toshiba laptop that allowed me to draw, colour and alter images on screen. I threw out thousands of dollars worth of paints, inks, colour markers, even three large filing cabinets stuffed with reference material collected over half a century. Everything I needed was now stored in that portable box of magical electronics.

However, I found that drawing on a slippery screen was like roller skating on ice, no better than drawing on a whiteboard. Give me a chunk of chalk and an old blackboard any day, plenty of drag and grip, so I still draw the black linework on paper, scan that into the computer and colour it electronically.

What does your family think of your cartoons?

Lenore was a qualified creche and kindergarten teacher when we married and she used my cartoons for the children as well as in newsletters, posters and advertising material for fetes and functions because they communicated, not only with the children but their parents as well.

When our three girls were little, she was the production assistant for a Saturday morning children’s program on Channel 9 Brisbane called Over Anne’s Rainbow. I cartooned for her regularly and our kids were often the mini-stars.

Later we created a weekly children’s activity page called “Kids Space” that was syndicated to about 50 regional newspapers across Australia. We both had a lot of creative fun using cartoons to illustrate the creative activities and puzzles. As the girls got older, I was always cartooning for them to add a touch of fun to their personal and general school projects and social activities.

I enjoyed the freedom and solitude of working in my home studio, despite the incredibly long hours. I believe our girls did, too, as one or other parent was always available. I remember one cold, rainy winter day when I got an urgent call from the school sick bay asking if I could collect three little girls who were all suddenly unwell. The triple request for McDonalds on the way home, rather than a visit to the doctor confirmed my suspicions, and as a punishment they had to spend the afternoon drawing on the warm studio floor.

Nowadays I’m constantly drawing birthday cards for our family and friends, six grandchildren and all their friends as I’m told, “They’re so much better than cards from the shops, Papa.” Perhaps I’m still getting conned, but I enjoy it!

What’s it like cartooning at MercatorNet?

That’s another easy question. I love it! How many people are lucky enough to be able to keep on doing what they always loved doing long after they retired from the hassles of commercial business and all its worries.

Not only that but the articles and subject matter of every one of the hundred weekly cartoons that we’ve created together align perfectly with my personal beliefs and values. One thing I could never do is draw a cartoon that supports or promotes any idea or concept that went against them. Even before I retired I knocked back several profitable cartoon job proposals that didn’t meet that standard.

We work to a tight schedule as topicality demands that an article might often be in its early draft stages on the morning of publication day, Friday. It takes an afternoon of nonstop, pencilling, inking and colouring before it’s emailed back to Sydney and posted online. The good news is we’ve always met the dreaded deadline 100 per cent of the time over 100 weeks.

So thank you, MercatorNet! And thanks to all your readers around the world who have enjoyed my “silly pictures”.

![[The Good Oil] Stuff Up of the Day](/content/images/size/w1304/format/webp/2024/09/Stuff-up-image-1.webp)