Table of Contents

If you don’t have a Silver level membership yet you are missing out on our Insight Politics articles.

Today is a FREE taste of an Insight Politics article by writer Chris Trotter

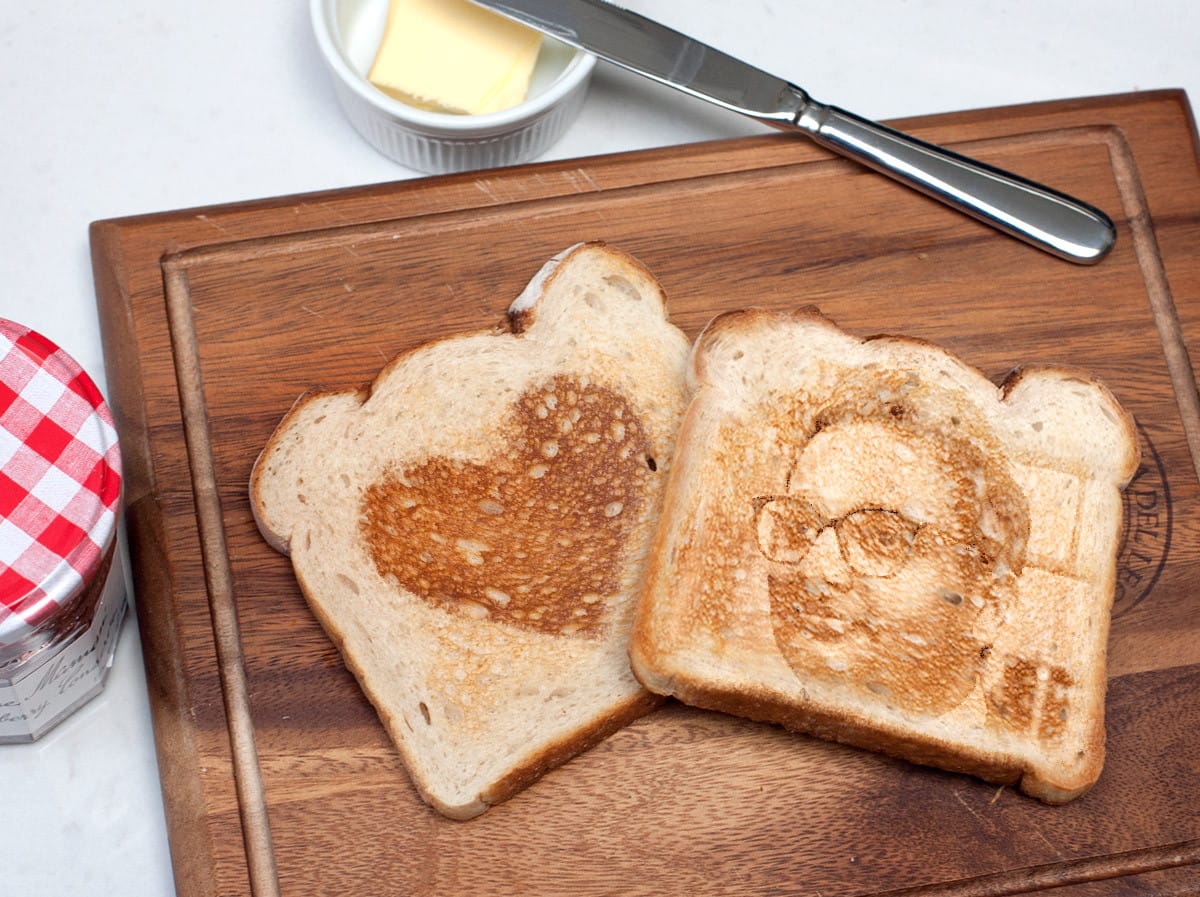

Dr Gaurav Sharma Is Toast

When the Party is king, backbenchers are peasants

“WHAT HAPPENS NOW?” The newly elected Member for Manurewa, Phil Amos, still not quite believing that his days as a secondary-school teacher were over, had rung the Leader of the Opposition, Arnold Nordmeyer, for guidance.

“Well,” said Nordy, “we’ll probably have a Caucus meeting sometime in February. [The conversation was taking place in November.] And since the Nats don’t like to call the House together too early – far too many farmers in their Caucus, with far too much to do – things won’t get really busy around here until about the middle of the year.”

“What am I supposed to do until then?” Phil responded plaintively.

The Labour Leader chuckled. “My advice, Phil, is to talk to as many people as possible, and just use the time to get to know your electorate.”

That’s the way it was for a brand new Labour MP, in a brand new seat, back in 1963.

The brand new Labour MP for Hamilton West, Dr Gaurav Sharma, arriving at Parliament 57 years later, faced a radically different set of expectations.

Very few people in 1963 would have considered it either appropriate or accurate, to refer to Members of Parliament as “our employees in Wellington”. Most voters understood that they had elected a representative: someone whose duty it was to reflect, protect and defend the interests of their electorate. The idea that one’s MP is nothing more than a glorified civil servant: a person expected to turn up for work every day, do their “job”, and collect their (excessive) pay, is a much more recent notion.

The transformation of our elected representatives into our employees began in earnest in the mid-1980s under David Lange’s Labour Government. Labour’s win in the snap election of 1984 had bequeathed Lange and his coterie of radical reformers an additional 13 seats and an overall parliamentary majority of 17.

In the light of what Lange and his coterie of “free marketeers” had planned for the country, this sudden influx of new, non-House-trained, backbenchers was not entirely the triumph it appeared to be. As Mickey Savage discovered between 1935-38, a caucus swollen with a host of new and idealistic MPs can cause all kinds of problems for their Cabinet colleagues.

The idea of backbench MPs with nothing to do for months except “talk to as many people as possible, and just use the time to get to know your electorate” would have struck terror into the hearts of those who were just about to unleash what was to become known as “Rogernomics” on New Zealand. Since the Devil makes work for idle hands, these new MPs needed to be kept as busy as possible.

The radical changes to the running of Parliament and, therefore, to the lives of backbench MPs, in the mid-1980s, are usually attributed to the formidable organisation powers of Geoffrey Palmer. When he was through, Parliament sat for a far greater portion of the year and according to a strict calendar. The days of not calling Parliament together until after the lambing season, were well and truly over!

In Phil Amos’s day, managing an MP’s electorate duties was usually left to their long-suffering spouses. An electorate office was something MPs either paid for themselves, or had their party pay for them.

Why so niggardly? Because representing one’s fellow citizens was not considered a full-time “job”. Rather, it was an obligation voluntarily assumed by worthy citizens out of a strong sense of public duty. Obviously, this high-flown notion of “service” left working-class representatives at a considerable disadvantage. Acknowledging the system’s inherent class bias, the state eventually agreed to maintain MPs and their families. For many years, the sum involved was roughly equivalent to a senior teacher’s salary.

Palmer’s reforms swept this all away. To assist MPs to fulfil their increased parliamentary duties, a new body – Parliamentary Services – was established to supply full-time staffers to each MP at the taxpayers’ expense. Back in their electorates, the state provided MPs with office space and secretarial staff. Hitherto an unencumbered representative of the people, every MP now found themselves managing staff – just like the bosses! In recognition of this radical revision of their role, MPs also found themselves “earning” considerably more than a senior teacher.

Palmer’s reforms were proof of the old adage: “To keep a man docile – give him something to lose.” In 2022, that “something” amounts to $170,000 – plus allowances.

The transition to MMP only made the lives of MPs more vulnerable. When the whole of Parliament had been composed on MPs elected directly by their communities, the ability of their parties to discipline and punish was limited by the consideration that any unfair victimisation of a local member could easily result in the loss of the seat. With the advent of Party Lists, however, that local link was eliminated. Dissenting List MPs were now at the complete mercy of the party leadership. Not only that, the acute vulnerability of List MPs encouraged them to become the leadership’s ruthless enforcers. To keep themselves high on the List, they would make the lives of dissenters a living hell.

Rounding out this Kafkaesque nightmare, was the anomalous position of Parliamentary Services.

Constitutionally speaking, the House of Representatives is composed of exactly that – representatives. While MMP, with its Party Lists, was finally able to force the idea of party representation onto the statute books, the core principle of Westminster democracy is that the MP is free, sovereign, and independent. In an ideologically consistent political universe, therefore, Parliamentary Services would leave the choice of staffers up to the MP, supplying only the funds necessary to pay them. Once appointed, they would serve at the pleasure of the Member – in much the same way as US presidential staffers.

Here, parliamentary staffers are classed as the employees of Parliamentary Services – a ridiculous arrangement given the intensely political nature of their jobs. Inevitably, when things turn to custard – as they obviously have, on more than one occasion, with Dr Sharma, the public service wallahs at the top of Parliamentary Services turn to the Party Whips to sort matters out. Constitutionally, it should be the MPs’ preferences that hold sway, but in the real world, Parliament is the domain of party politics: leaving the individual to the tender mercies of the collective – and its designated bullies.

Dr Sharma is toast.

If you enjoyed that FREE taste why not subscribe to a SILVER level membership today?

You will not only get access to Insight Politics articles like the one above but you will also gain access to all our puzzles, SonovaMin and BoomSlang’s fantastic cartoons, and our private members’ forum MyBFD as well as enjoying ad-free viewing.

$25 a month ($6.25 a week) (89c a day)

$300 a year