Table of Contents

Today Non- Subscribers get a FREE taste of what they are missing out on.

Have a read of this Insight Politics article then decide whether or not you would like to subscribe to a Silver subscription or upgrade your existing Basic or Bronze level Subscription to Silver.

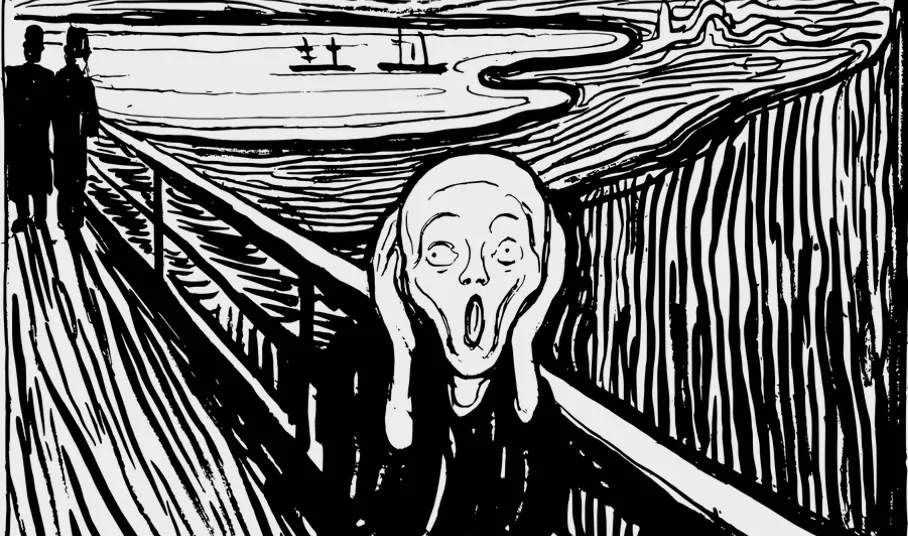

Tarrant’s Silenced Scream

“We have maintained a silence closely resembling stupidity.”

NEIL ROBERTS 1982

IN MY FRIDAY MORNING’S NZ Herald I read the following sentence. “Judge hands down harshest sentence in NZ history to man who murdered 51 people.” Compressed into that single sentence, no doubt written in great haste by an overworked and underpaid young journalist, is so much of this country’s current malaise.

Justice Cameron Mander did not hand down New Zealand’s harshest sentence to Brenton Tarrant – the perpetrator of the Christchurch Mosque Massacres. That honour (if honour it can be called) belongs to the last New Zealand judge to impose the death sentence.

So bereft are young New Zealanders of even a rudimentary understanding of their own country’s past, that a great many of them are entirely unaware that up until 1961 New Zealand judges were required by law to sentence convicted murderers to be hung by the neck until they were dead. The last person to suffer this fate – indisputably the harshest judicial punishment – was Walter Bolton, who went to the gallows in 1957 for poisoning his wife.

The four-day process of Tarrant’s sentencing exposed a great many deficiencies in contemporary New Zealand culture: its superficiality, emotional incontinence, intellectual vacuity and moral timidity. Our most alarming deficiency, however, incorporates all of the above. It is this country’s abiding fear of open and unfettered discussion and debate.

Day after day, over the past week, we heard and read excerpts from the statements delivered to the court by Tarrant’s surviving victims and the relatives of those he murdered. Already under a self-imposed obligation to limit their coverage of the sentencing process, New Zealand’s journalists regaled the public with a single, pre-approved story of anguish and courage. The even stricter legal limitations, imposed by Justice Mander, were adhered to by the print and electronic media without demur.

The entirely predictable result was one of unanimous, unequivocal and cathartic condemnation. New Zealanders were invited to share in the collective experience of Tarrant’s social execution in much the same way as the authorities once summoned their forebears to witness a murderer’s physical elimination.

That the news media was giving New Zealanders exactly what they wanted is indisputable. Tarrant had killed 51 human-beings with no more compunction than a high-country farmer picking-off 51 rabbits. Pretty much the whole country wanted the man to be sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. Justice Mander did not disappoint them.

Missing from the entire experience: from the moment Tarrant opened fire on 15 March 2019, to the moment he was led away to perpetual incarceration on 27 August 2020; was context. Tarrant’s own attempt to contextualise his actions: his online manifesto entitled “The Great Replacement”; was almost immediately banned by the Chief Censor, David Shanks. Declared “objectionable”, Tarrant’s “justification” for his crime was suppressed: available only to scholars and journalists approved by the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The message delivered by Shanks’ classification was accepted with scarcely a murmur of dissent across the entire New Zealand media. Henceforth, it would no longer be sufficient to merely condemn Tarrant’s crime. Henceforth, anyone wishing to write about it was expected to explain the tragedy purely and simply in terms of the perpetrator’s aberrant white supremacism. The unavoidable corollary of this position (which fast became the official media “line”) was that any attempt to set Tarrant’s massacre in the context of other terrorist massacres, especially those carried out by Muslim extremists, was ipso facto, “Islamophobic” and proof, prima facie, of utterly unacceptable white supremacist sympathies.

At a stroke, the voluminous international literature on the preconditions, motivations and psychological predispositions for acts of terrorism was shunted to one side. Comparisons between Tarrant and the perpetrators of ISIS’s atrocities were similarly discouraged. Instead, the debate homed-in on the allegedly inherent and universal white supremacist racism of New Zealand society. Bitter criticisms were directed at New Zealand’s national security apparatus for its failure to prioritise the threat posed to Muslims by white supremacist individuals and groups.

Once again, history – even recent history – was effaced. Many, perhaps most, mainstream journalists and commentators considered it profoundly insensitive – bordering on racist – to remind New Zealanders that:

Between 2012 and 2013 the number of deaths from terrorism had increased by 61 percent. In 10,000 terrorist attacks 17,958 people had been killed. According to the BBC: “Five countries – Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria – accounted for 80% of the deaths from terrorism in 2013. More than 6,000 people died in Iraq alone.” Just four terrorist groups were responsible for the deaths of two-thirds of 2013’s nearly 18,000 terrorist victims: Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, Boko Haram and the self-styled Islamic State. The Global Terrorism Index reported that: “All four groups used ‘religious ideologies based on extreme interpretations of Wahhabi Islam’.”

So pervasive was the notion that New Zealand’s Muslim community must be protected from the evils of white supremacism that Tarrant was told in no uncertain terms that he would not be permitted to say anything by way of explanation or mitigation that might re-traumatise his victims, harm the broader Muslim community, or in any way outrage common public decency. Denied the long-established right, as a prisoner facing sentence, to address the court without the fear of being interrupted and censored by the Bench, Tarrant chose to remain silent.

Thus was New Zealand denied the benefits Norway gave itself by allowing Anders Breivik, its own white supremacist mass killer, to address the Oslo Court, uninterrupted, before sentencing. Unlike New Zealand, Norway got to hear, from the perpetrator’s own lips, the utterly spurious justifications for his dreadful deeds. They learned just how inadequate and ignorant Breivik was: how unheroic; and, ultimately, how pathetic and pitiful. By being placed squarely in the spotlight’s glare, Breivik ceased to be the towering shadow of people’s darkest fears; becoming, instead, something small and weak and utterly contemptible.

What a pity our government declined to be guided by the Norwegians. If they had not, then Tarrant would very likely have broken his own evil spell. As it is, he was allowed to sit impassively through scores of anguished victim statements, wreathed in precisely the sort of unanswered questions that allow even the most terrible deeds to go on living and breathing in a nation’s heart. We have given him the consolation of knowing that with every victim’s cry of pain and shout of anger, the splinter of his terrorism is driven deeper and deeper into New Zealand’s collective memory.

The Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern’s response to Tarrant’s sentence was as poetic as it was short:

“The trauma of March 15 is not easily healed but today I hope is the last where we have any cause to hear or utter the name of the terrorist behind it. His deserves to be a lifetime of complete and utter silence.”

Her hope is vain. A nation that cannot discuss and debate the nature and purpose of a man like Brenton Tarrant may believe itself protected by the stupid silence it maintains. Alas, men’s thoughts cannot be measured in decibels – even when they scream.

Before the onset of a thunderstorm, there is always a moment of stillness – and then the lightning flashes.

Did you enjoy reading that?

Subscribe to a Silver subscription or upgrade your existing Basic or Bronze level Subscription to Silver today.