Table of Contents

Dr Oliver Hartwich

nzinitiative.org.nz

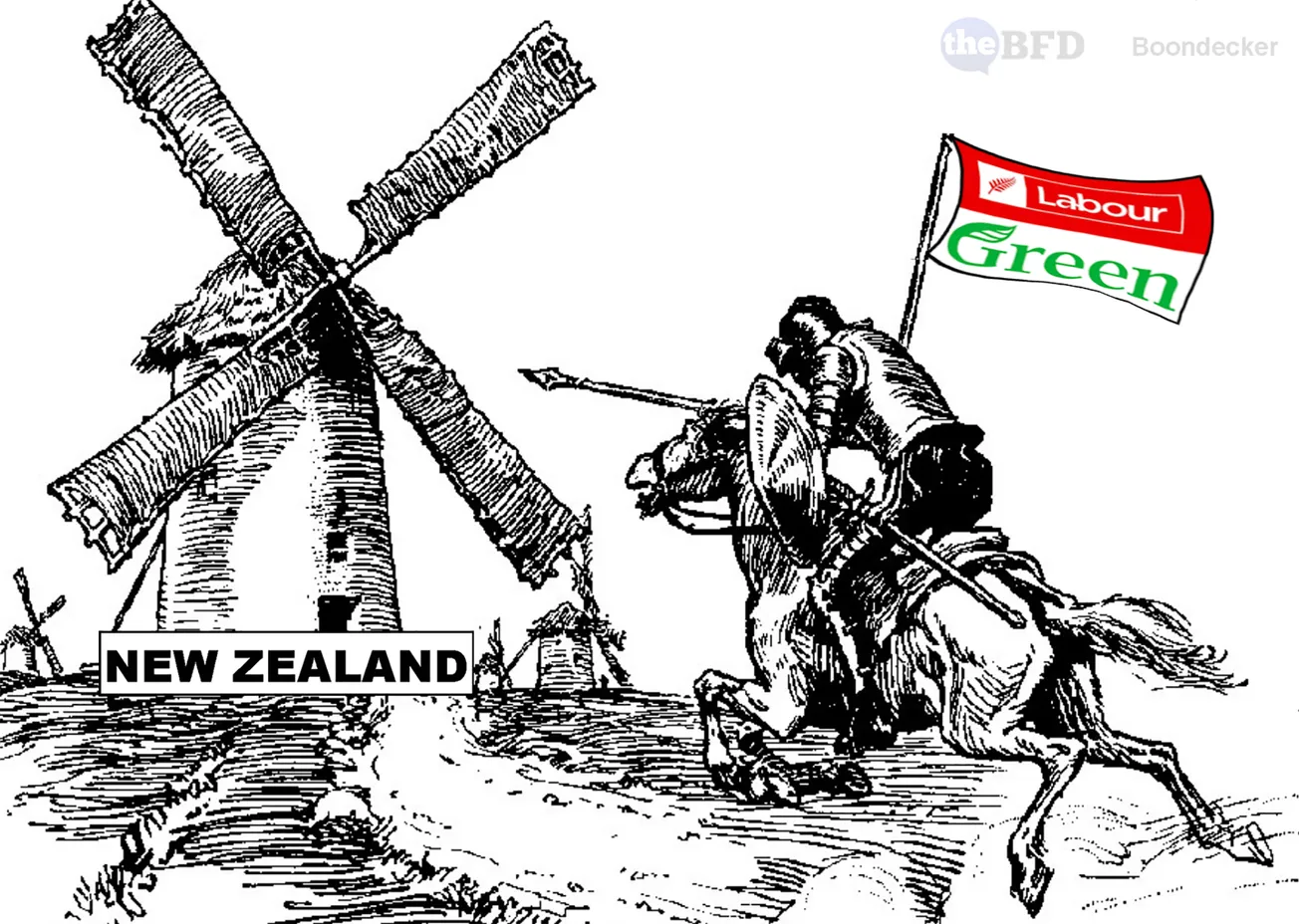

The Green Party has declared its wealth tax will be a red line in any coalition negotiations.

And because Labour knows this, the larger party left the door wide open. Rather than ruling out the Greens’ plans, both the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance did not rule them out.

In separate interviews, both Jacinda Ardern and Grant Robertson said these plans were not Labour’s. No wonder, because Labour does not want another election campaign under the cloud of tax policy. Labour perhaps has sympathy for the plan but presently finds it convenient to blame its eventual introduction on a future coalition partner.

With the prospect of the next Government freed from the constraint of New Zealand First, Winston Peters will not be able to stop the plan as he did with the capital gains tax last year. And because of that, there is a considerable chance a form of wealth tax will appear after this September’s election.

The Greens’ proposal is a wealth tax on everything. It creates a tax-free allowance of $1 million per person after which a new tax kicks in at 1 percent. Everything above $2m of assets is then taxed at 2 percent. There are no further exemptions for the family home or anything else.

The Twittersphere loves the idea, and surely the rich can afford a 2 percent tax on their assets, right? Except, this is not a one-off tax but an annual one which changes the picture significantly.

Say a 40-year-old owns a farm worth $10m (assuming no further assets). For simplicity’s sake, let’s ignore asset price changes and inflation. The first million dollars will always be tax free; the second million will always result in $10,000 of tax. Whatever remains is taxed at 2 percent.

In this scenario, by the time this farmer reaches retirement age at 65, a total of $3,370,550 of his or her original asset of $10m would have been taxed away. From the farmer’s perspective, the 2 percent wealth tax is the equivalent of a 33 percent expropriation. Worse, the wealth tax will carry on at the same rate after the farmer’s retirement. Should the farmer be lucky enough to reach 90 years of age, the wealth tax would have consumed almost half the original capital.

The same tax logic applies to start-up entrepreneurs or indeed any other investors. And while farmers usually have strong ties to their properties, other asset holders may be more mobile.

Entrepreneurs, the retired or asset-rich expats may think twice about remaining in New Zealand if they are to be subjected to one of the most onerous wealth tax schemes in the world.

And just in case these cohorts of mobile and often highly qualified people were not sure about what to do, the Greens’ income tax proposals give them yet another reason to consider their future here. From $100,000, the party wants to introduce a new tax band at 37 percent and yet another at 42 percent for incomes exceeding $150,000.

The proposed tax bands would shift New Zealand income tax rates closer to Australia’s rates. Actually, Australia’s highest rate of 45 percent only kicks in from $A180,000 which means for some Kiwi professionals, Australia might even offer them lower taxes. But that, of course, ignores that incomes across the Tasman are on average about a fifth higher anyway. So why would these professionals want to stay here?

Should the Greens’ policy ever be introduced, we could expect an exodus of people with capital and high incomes. In non-technical terms, it would trigger a ‘brain drain.’

But wait, there is more.

Not content with driving away the qualified and asset-rich, the Greens also want to reduce the incentives for low-skilled people to work. A new guaranteed weekly income of at least $325 would be handed out to everyone not in employment, including students. This would be topped up by $110 for solo parents. The existing Best Start payment would be expanded from $60 per child to $100 per child and made universal for children aged up to three (instead of two).

So, for people with lower skills, these payments would make it less attractive to seek employment while lowering the incentives to upskill. Recall that, according to a recent Ministry of Education report, the returns to education have fallen substantially due to a levelling of incomes as a result of minimum wage increases.

Meanwhile, for employers, the Greens would make it less attractive to take on low-skilled workers because the party simultaneously wants to legislate for substantial increases in the minimum wage.

Pardon my French, but these proposals are bonkers. If I wanted to ruin the economy, this is precisely what I would do.

It beggars belief that any party would come up with this madness during a severe recession. It is even more astonishing that otherwise sensible commentators could defend these proposals as they have done.

Should the Greens replace New Zealand First at the Cabinet table, we would be in for a wild policy ride, and not just on tax. Trade policy would also likely shift, too. And of course, we would see climate policies going well beyond the Zero Carbon Act and the Emissions Trading Scheme.

From its 2 percent level of support, New Zealand First will be struggling to make it back to Parliament. Labour’s 50 percent share is unlikely to survive the election campaign and it will return to normal, pre-Covid-19 popularity.

Provided the Greens return to Parliament, a Labour-Greens coalition is a plausible election outcome.

Following its first taste of power outside cabinet, the Green Party will not be content with a place on the crossbenches to give confidence and supply. Was it not Winston Peters who in this current term demonstrated the high amount of influence even a small party can wield in an MMP coalition? The Greens would surely want to emulate that. Except with that strategy, it will accept its status as a fringe party (just like NZ First).

It is a shame that the Greens’ first encounter with political power has not turned the party into a more centrist, mainstream force (which, incidentally, is the opposite of what happened to Germany’s Green Party after its first government experience). Instead, the New Zealand Greens’ first taste of government made it more ideological and drove it to the fringes of politics.

For the Greens’ long-term success, the party would be wise not to focus on its fringe supporters –which might just get the party over the 5 percent threshold – but instead on the centre of society which could make the Greens a mainstream force in New Zealand politics.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.