Table of Contents

Axelheart

I travelled to Paris in my early twenties – while on the quintessential OE based in England – visiting the usual tourist spots, including Versailles.

Despite my ignorance of the background of the French Revolution, one doesn’t need a history degree when confronted with the magnitude of the Palace of Versailles, the vast grounds, and glaring palatial opulence, to understand why the sans-culottes (peasants) felt aggrieved.

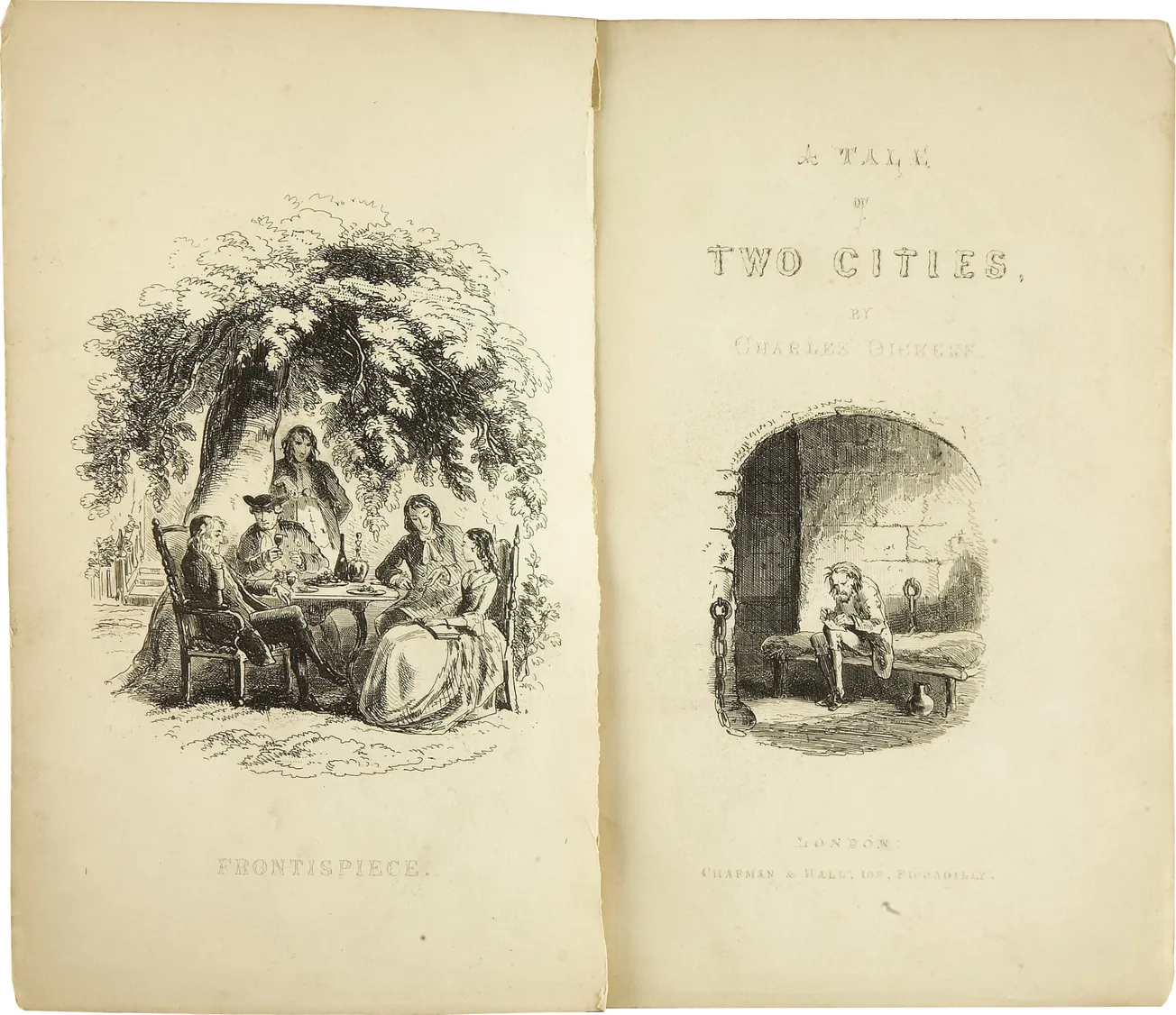

My father’s copy of A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens gathered dust on my bookshelf, patiently waiting to be picked up: a small burgundy book with fine paper and gilded edges but worn around the bottom and sides – a testament to its age and number of readers. This book has all the time in the world, yet I don’t.

Despite being a keen reader, I’ve avoided the book. Dickens required too much effort to comprehend when there are a million books to be read (and life is too short); therefore, I ignored one of the world’s best-known authors, because I failed to understand the prose and lacked the patience to try.

Yet, the novel beckoned. Hearing “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times” at a cricket game in summer, (which, incidentally, is an appropriate description of the game) and recently reading a contemporary book based in modern day New York and Paris where the author cleverly wove in the French Revolution.

The ghost of Dickens has all the time in the world, yet I do not, so I surrendered – the pages breathed again.

I struggled with the novel in stages; the language, words, phrases, the flow, but pressed on and eventually grew somewhat used to Dickens’s style. I almost abandoned it early on, but knew if I did, that would niggle – resulting in missing out on well-written powerful phrases, quotes, imagery and the dichotomy of the author’s humour, for instance, when people joked about the guillotine:

“It was the popular theme for jests; it was the best cure for a headache, it infallibly prevented the hair from turning gray, it imparted a peculiar delicacy to the complexion, it was the national razor which shaved close: who kissed La Guillotine, looked through the little window and sneezed into the sack.”

The sea imagery depicting the storming of the Bastille by the Parisiennes:

“With a roar that sounded as if all the breath in France had been shaped into the detested word, the living sea rose, wave on wave, depth on depth, and overflowed the city to that point. Alarm-bells ringing, drums beating, the sea raging and thundering on its new beach, the attack begun.”

You can see, feel, and hear the unstoppable power, borne from years of desperate hunger, oppression, degradation and hence, unbridled fury and vengeance. Prolonged and rising floodwaters that have burst their banks – now a raging torrent.

Through the prose of Dickens, you witness the consequential destructive and appalling face of this Revolution – the Reign of Terror – the force of the patriots condemning thousands of their own people to death by the “figure of the sharp female” – La Guillotine.

One of the key fictional drivers of this uprising, Madame Defarge, echoes this immense force in reply to her husband, Monsieur Defarge, who essentially says The Terror should cease: “but one must stop somewhere.”

Madame Defarge replies two pages later: “Then tell wind and fire where to stop,” returned madame; “but don’t tell me.”

And, of course, the famous and prophetic quote that begins the story:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way…

I used to think life is too short to waste on reading a classic, but maybe life is too short not to read a classic.