Table of Contents

David Thunder

David Thunder is a researcher and lecturer at the University of Navarra’s Institute for Culture and Society.

Dáil Eireann, the lower house of the Irish Parliament, has just passed the most radical hate speech law in the history of the Irish State, a law so radical that it could potentially criminalise material in your “possession” that you have never made public, if that material is deemed by a judge to be liable to incite hatred and you cannot prove it was exclusively for personal use.

The likely effect of this law, if it is passed in its current form in the Seanad (Senate), will be to create a chilling effect around any speech that could be construed as critical with respect to “protected categories” such as sexual orientation, “sex characteristics” (which I can only assume refers to someone identifying as a man or woman), gender, religion, and so on. It will also generate an atmosphere of insecurity for many citizens, due to the hopelessly vague and subjective manner in which hate speech offences are defined.

Let’s begin by working through a few key elements of the version of the Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hatred and Hate Offences) Bill 2022 that was passed a few days ago in the Dáil:

- First, “protected characteristics” are race, colour, nationality, religion, national or ethnic origin, descent, gender, sex characteristics, sexual orientation, and disability.

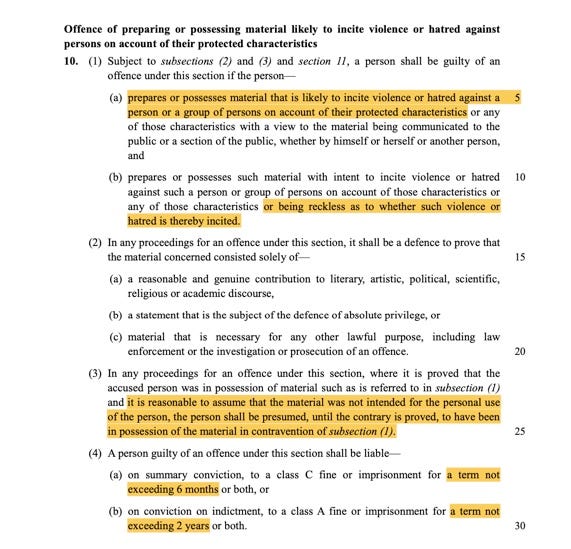

- Second, the bill defines an offense of “possession of material likely to incite violence or hatred against a person or group of persons on account of their protected characteristics with a view to the material being communicated to the public.”

- Third, the bill stipulates that if it is “reasonable to assume that the material was not intended for…personal use,” then “the person shall be presumed, until the contrary is proved, to have been in possession of the material (with a view to the material being communicated to the public).”

In practice, these provisions mean that a text on your computer that references one of the protected groups and is deemed by a prosecutor to be “likely to incite violence or hatred” toward said group, may land you before a judge, and eventually, in jail, just because the prosecutor and judge decide “it is reasonable to assume” you were going to publish it. They don’t need to prove to you that you intended to publish it somewhere. On the contrary, you need to prove to them that you did not intend to publish the offending material.

So what is wrong with this bill?

First, you can be charged with something that amounts to a thought crime: possessing material (e.g. thoughts in writing) that a judge (i) “reasonably assumes” that you intend to publish; and (ii) believes would likely incite hatred or violence toward a protected group. Remarkably, under this legislation, you can be charged and convicted of a hate speech crime without publishing a single word, based exclusively on a sentence someone found in your “possession,” that a prosecutor and judge “reasonably assumed” it was your intention to publish. So this bill makes it the business of government to worry about the appropriateness of your unpublished thoughts, and to put you in jail if they “reasonably assume” you intended to publish them!

Second, any law that defines as a criminal offence the possession or publication of material “likely to incite hatred or violence” is inherently flawed for the simple reason that almost any criticism, satire, or negative commentary directed publicly at an individual or the group he or she belongs to, could, potentially, incite hatred against them.

Whether it does so depends on something that is entirely outside the control of the speaker, namely the character, temperament, and psychological profile of the listener. For example, for someone strongly predisposed to racism, it might be sufficient to just hear “black” in a sentence or notice that the subject of a criticism is black, to be moved to hatred or even violence toward blacks. Are we seriously suggesting that a speaker should be held criminally responsible for the wildly varying emotional responses that his or her words may evoke in his or her listeners?

Third, this bill creates hopelessly vague offences, that provide no certainty to citizens about the conditions under which they may be prosecuted, fined or imprisoned. Vague and uncertain laws create an environment of fear and insecurity, the very opposite of what we expect under rule of law. Imagine you are a judge and you must decide whether content is “likely to incite violence or hatred” against a protected person or group: On what objective basis can a prosecutor or judge determine the difference between reasonable criticism of the behaviour or choices of a protected group (whether trans activists, this or that immigrant or religious community, or gays pushing for adoption rights), and criticism likely to “incite hatred or violence” toward the protected group?

What non-arbitrary criterion can guide a judge in drawing the line between fair democratic debate and criticism and hate-inciting commentary and criticism? And is a judge supposed to be guided by the sensibilities of a population pre-disposed to hatred, or a population of more moderate and balanced temperament? What sort of emotional or psychological profile should a judge assume when deciding a given utterance is “likely to incite hatred” in the heart of the listener?

A fourth problem with this bill is that it provides ample pretext for an activist prosecutor or judge to use the law to punish citizens who dissent from their political or ideological opinions. Hopelessly vague categories serving as grounds for prosecution are likely to be applied according to prosecutors’ and judges’ subjective sense of what is and is not “hate-inciting” content.

A law infected with this level of vagueness will easily become a conduit for the subjective opinions and ideologies of the interpreter. This means that public officials, whether police, prosecutors, or judges, will be able to use their power, if they so wish, as an instrument of political and ideological domination, dressed up under hopelessly vague language. For example, a judge who believes that biological sex is passé might interpret hard-hitting criticism of the trans agenda as “incitement to hatred” rather than reasonable democratic debate.

Last but not least, it can hardly be doubted that a law like this would have a chilling effect on free speech, given that all critical discussions of protected groups and their behaviour would have the threat of prosecution hanging over them. Indeed, it could even have a chilling effect on private conversations, since an email sitting on my computer that I shared privately with a friend could eventually implicate one or both of us in an offence under this Bill.

What is at least as disturbing as the content of this bill is the fact that it breezed its way through the lower chamber of Ireland’s national parliament with almost no opposition. Of the TDs who bothered to show up, a paltry 14 (out of the 160 who compose the full Dáil) voted against it.

This article has been republished with permission from The Freedom Blog,