Table of Contents

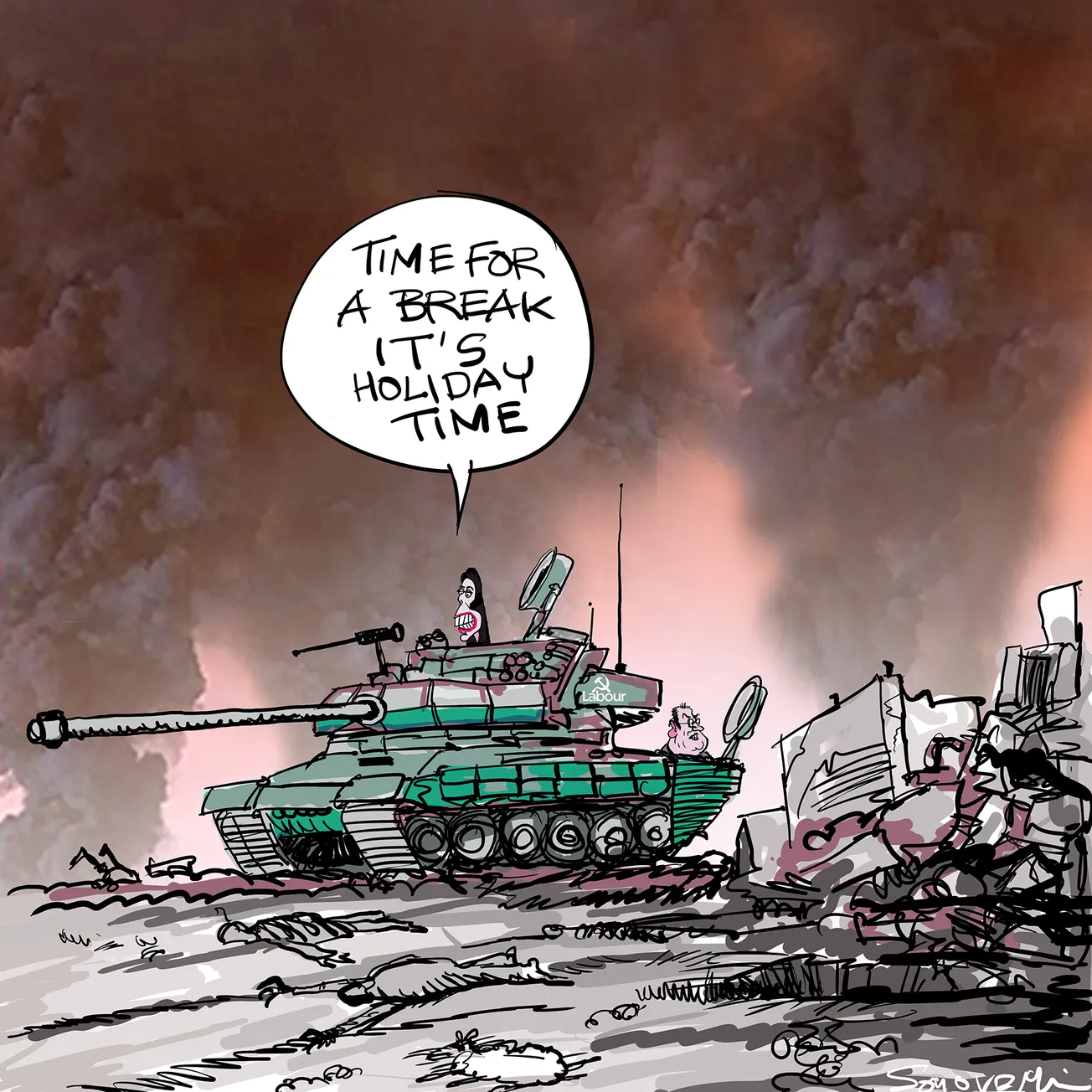

A tactical withdrawal is said to be the most difficult of all military operations. A commander has to take his troops backwards while maintaining contact with the enemy and not being pushed into a headlong retreat. The challenge is to not lose discipline during the operation.

It can become necessary when the enemy is simply too strong and an army needs to leave the battlefield to avoid a crushing defeat, or it can be simply to pull back to reach an area that is easier to defend.

Trailing National in the polls, Ardern has decided to retreat and present a smaller target to opponents by postponing the implementation of contentious policies or reducing their scope.

These have already included delaying a draft plan in response to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples until 2024 while watering down “hate-speech” legislation, and immigration restrictions for nurses.

More back-pedalling is in sight. In mid-December, Ardern advised she had asked ministers to “go away and look at our legislative programme” over Parliament’s summer break, to “pare back” policy initiatives, because the government needed “an absolute focus on the economic situation” in 2023.

“We need to be ensuring we are supporting New Zealanders and have a clear eye on that issue. We do need to trim back the amount of issues that we are progressing as a government,” Ardern said.

In other words, a retreat in some areas and regrouping in order to mount a counter-attack focused on economic policy (no doubt including generous election sweeteners).

Ardern is fond of characterising a coming year with a slogan. So, 2019 was supposedly the Year of Delivery, while she dubbed 2021 in advance as the Year of the Vaccine.

She is yet to slap a snappy slogan on 2023 although she may favour something heroic such as the Year of Economic Resurgence.

The Prime Minister has also promised a Cabinet reshuffle in the hope of restoring voters’ confidence in her government.

The need for such defensive manoeuvres represents a stunning reversal of fortune since late 2020 when Ardern won the first outright majority of the nation’s MMP era and her personal popularity ratings were stratospheric.

A poll conducted by Curia for the Taxpayers’ Union in mid-December put Labour on 33.1 per cent (with National climbing to 39.4 per cent) while Roy Morgan showed its support at 25.5 per cent — only slightly higher than the disastrous results in mid-2017 when Andrew Little decided he should step down in favour of his deputy, Jacinda Ardern.

In December’s by-election for the bellwether seat of Hamilton West, the Labour candidate won only 30 per cent of the vote.

In light of such dismal results, casting the paring-back of policy in a positive light will be a challenge for Labour’s strategists, who will be hoping that voters won’t see the government as simply trying to save the furniture.

They will also want to find a way to convince the public that Ardern has good reasons for continuing to defend electorally toxic ground — notably Three Waters — even as she suggests abandoning other less contentious policy areas.

Despite the Prime Minister predictably painting a retreat as a result of her government having ambitiously taken on too many issues to deal with adequately, it is obvious she is making a virtue of necessity.

Alongside the government’s well-deserved reputation for being incompetent in delivering even the basics of what the public wants — including roads free of potholes — it seems to have a perverse desire to give them what they don’t want, not least an expensive unemployment insurance scheme and a merger of RNZ and TVNZ.

Desperate times call for desperate measures, but not everyone is convinced Ardern’s prescriptions will help.

Former Labour Cabinet minister Richard Prebble is highly sceptical about the value of the Cabinet shake-up Ardern has promised to make early in the New Year — designed, she said, to utilise “the excellent talent” in the Labour caucus.

Three ministers — Poto Williams, Aupito William Sio and David Clark — have announced their intention to resign at the next election. These departures will excite ambitious caucus members but, as Prebble pointed out in the NZ Herald, promoting someone to a new Cabinet portfolio in an election year when they are not confident or experienced in bending ministries and government departments to their will could only be described as “suicidal”.

And, he noted, the reshuffle is likely to be politically inconsequential anyway because “Ardern is not going to sack the senior ministers who are responsible for inflation, runaway government expenditure, rising crime and co-governance.”

That conclusion has been bolstered by the fact there have been no obvious consequences for Nanaia Mahuta engineering the passing of an entrenchment clause in the Three Waters legislation with Green MP Eugenie Sage in November.

Ardern publicly abased herself by covering for her unrepentant minister and her underhand assault on constitutional convention by declaring it was a team “mistake” — thereby implicating herself and every other minister in a devious and damaging plot.

Her refusal to explain to the public exactly how the “mistake” occurred and who was responsible has been interpreted as an unwillingness to confront Mahuta and sack her for subversion. The debacle signalled to many a Prime Minister who had lost effective control of her Cabinet.

Ardern has also made it clear that Three Waters will not be jettisoned in any recalibration of policy — again giving credence to the belief she is a puppet forced to dance to the tune played by Mahuta and the Maori caucus.

Normally a risk-averse politician, Ardern would have done a screeching u-turn on the widely despised Three Waters project a long time ago if the decision was up to her — just as she did in abandoning her cherished capital gains tax and most of the hate-speech legislation she was keen to pass into law after both were roundly opposed.

As a result of her timidity in dealing with Mahuta, Ardern looks more than ever as if she is Prime Minister in name only. The charge that the government is itself co-governed — with the Maori caucus holding the whip hand in the arrangement — is looking more and more plausible.

The impression that her Cabinet is fracturing along such lines hasn’t been helped by Attorney-General David Parker telling the NZ Herald in November he had pushed back against “strong pressure” from the Maori caucus demanding 50:50 co-governance in the legislation replacing the Resource Management Act.

Apparently, he had belatedly discovered a “tension between democracy and the Treaty” in co-governance being implemented in spheres beyond managing physical features such as the Waikato River.

“Too little, too late” has been a common verdict on Parker’s attempt to distance himself from co-governance among voters hostile to the policy.

Unfortunately, Ardern herself has become electoral poison to many people, including a big chunk of those who voted for her in 2020.

It will be very difficult to rally her troops when she has become so personally polarising that her deputy, Grant Robertson, has already signalled that public walkabouts will quite likely not feature in Labour’s election campaign — for the Prime Minister or her senior ministers.

The cancellation of Ardern’s Waitangi Day barbecue breakfast over “security concerns” is an early sign of just how difficult public campaigning will be for her.

A Prime Minister appearing only in closely controlled environments — perhaps including campaign HQs and schools where she feels at home and can’t be easily heckled by protesters — will speak volumes about just how deeply unpopular the government and its leader have become for many voters.

Meanwhile, Christopher Luxon and David Seymour will be out and about happily advertising their wares, their public presences contrasting with her sequestration.

What must be particularly galling for her is that Labour’s slide in the polls cannot even be attributed to a dynamic National Party. So far, Luxon has largely kept his powder dry. His strategy appears to be one recommended by Napoleon Bonaparte: “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

He has promised to repeal Three Waters but he has mostly avoided committing to much new policy. And when he found he had handed a hefty stick to Labour to beat him with by proposing lower tax rates for high earners, he did some adroit retreating of his own.

He quietly abandoned the policy, saying he didn’t want to add further fuel to the inflation fire after the Reserve Bank lifted the Official Cash Rate by 75 basis points to 4.25 per cent.

As pressure intensifies and the polls go against her, Ardern seems to be making mistake after mistake.

In the House on December 13, David Seymour questioned her about the proposed addition of religion to hate-speech laws.

Seymour: “How will New Zealand become a more peaceful and united country from the introduction of a law that allows people to be fined or jailed for ‘insulting a religion’?”

Having bowed to public pressure last year to not pass extensive new laws, Ardern appeared aggrieved that her slimmed-down approach of adding just religion to the existing protected groups of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins under the Human Rights Act was not fully appreciated as a compromise:

“As we have debated and discussed in this House many times before, we already have provision in our Human Rights Act to prevent incitement based on ethnicity or race. What we have simply done is add the word ‘religion’.”

In her next answer, she repeated the sentiment: “We have added now the additional word of ‘religion’…”

The Prime Minister has never understood the subtleties of the hate-speech debate but this was a doozy. Adding religion is not just an “additional word”. It is a whole new can of worms — and fundamentally different to the other protected categories because religious belief is not innate.

Furthermore, it is substantially similar to political belief. If you protect one you should logically protect the other, which is, of course, absurd.

Seymour continued to get under her skin with more questions she struggled to convincingly answer before she finally sat down and quietly exclaimed to Grant Robertson: “He’s such an arrogant prick!”

Seymour not only made sure her words made it into Hansard — the official record of parliamentary debates — but he also put her in a tactical bind by suggesting they both sign a copy of the page recording her words and auctioning it to help “pricks everywhere” by donating the proceeds to the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

Outmanoeuvred by an inspired piece of political one-upmanship, she had no option but to accept Seymour’s offer lest she look churlish and a poor sport.

Having been humiliated by her own Minister of Local Government as well as being snookered by the leader of a minor party in short order, Ardern is looking like she belongs to an unfortunate group of commanders — a general whose luck has run out.