Table of Contents

Carol Neilson

Carol Neilson is a space holder, writer, transformational mentor and devoted facilitator of yin yoga and mind-body-spiritual practices.

During the pandemic, the New Zealand Government implemented numerous impactful decisions and policies, many of which had unintended psychological consequences on those who had to enforce these policies/rules – at times eroding the unique relationship between the Government, the Ministry of Health and health professionals, and the general population.

The psychological consequences were particularly felt by medical staff who had to refuse families the chance to say goodbye to their dying loved ones, families who refrained from visiting vulnerable relatives due to fear of transmission, and doctors who compromised their knowledge, ethical standards and professional vows to follow the MoH prescribed pathway of care and treatment. Similarly, the Managed Isolation and Quarantine (MIQ) staff faced the daunting task of managing a volatile environment, catering to distressed and anxious returning families.

“Often, moral injury manifests as feelings of betrayal at the leaders and institutions that forced them into making these decisions in the first place…”

– Jonathan Moens.

Speaking out against these policies often resulted in marginalisation and job loss. Unfortunately, the Government and employers did not tolerate dissenting voices. As a result many found themselves trapped in an impossible situation and forced to stay silent – hostage to an untenable situation and in conflict with their moral code.

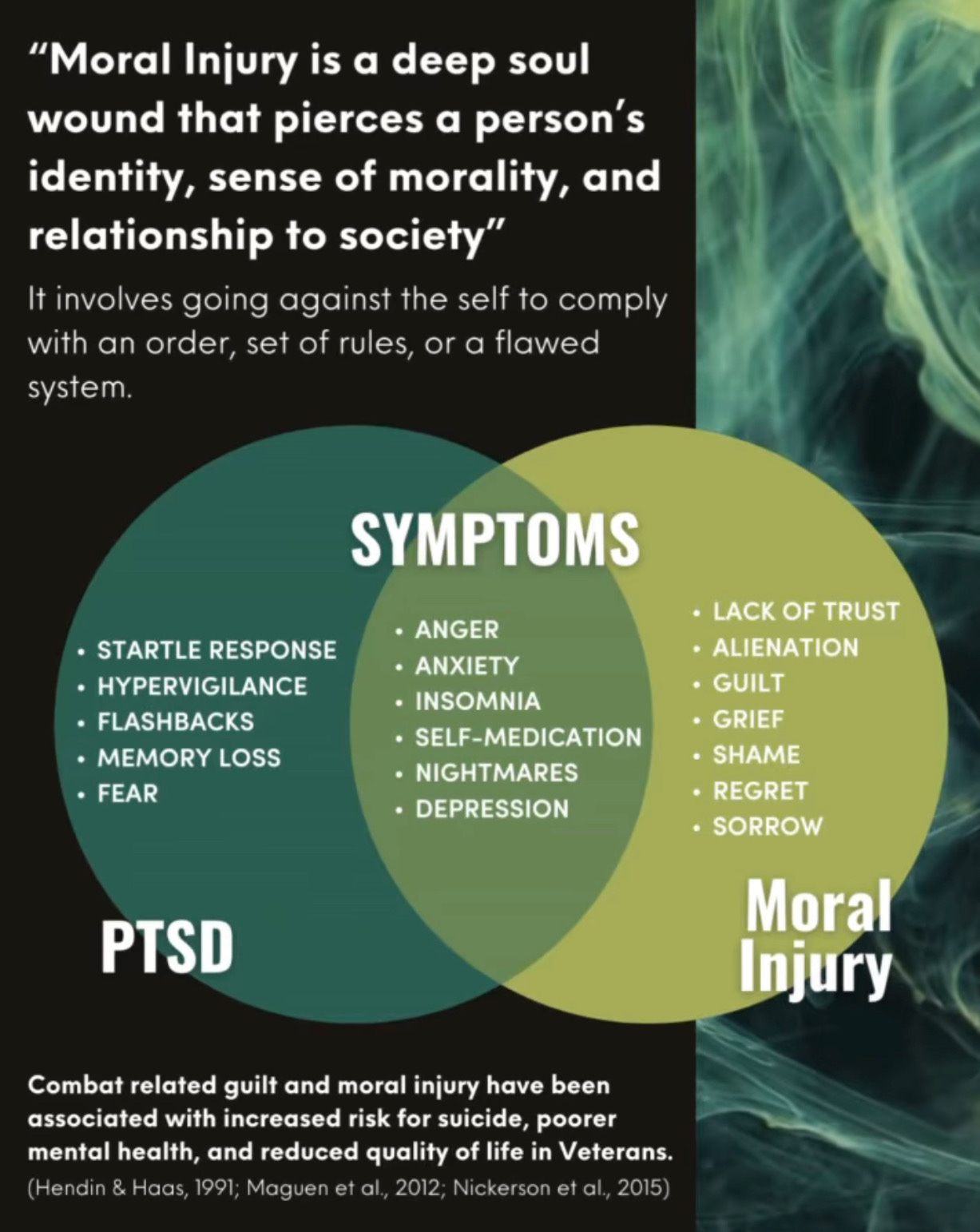

Now we have language emerging to describe the indescribable of what we have been through these past few years of the pandemic: moral injury. It’s a significant description of something intangible and misunderstood; it’s also described as “a deep soul wound that pierces a person’s identity, sense of morality, and relationship to society” (ii). Many describe moral injury as an invisible epidemic affecting millions post-pandemic.

Moral injury is understood to be the strong cognitive and emotional response that can occur following events that violate a person’s moral or ethical code.

The concept emerged from the field of psychology and was initially associated with the experiences of military personnel. However, it’s recognised as a broader phenomenon that can affect individuals in various professions and contexts. Unlike post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is primarily associated with traumatic events, moral injury stems from the internal struggle and anguish caused by the violation of one’s ethical code.

It sits in the same field as an ethical dilemma. It occurs when individuals are exposed to events or situations that contradict their fundamental beliefs about right and wrong, fairness, justice, or human dignity. This misalignment between one’s actions and deeply held values can result in deep psychological and existential distress.

“Moral injury is not considered a mental illness. However, an individual’s experiences of potentially morally injurious events can cause profound feelings of shame and guilt, and alterations in cognitions and beliefs (eg, “I am a failure”, “colleagues don’t care about me”), as well as maladaptive coping responses (eg, substance misuse, social withdrawal, or self-destructive acts). It is these challenged beliefs and altered appraisals that are thought to lead to the development of mental health problems, with a 2018 meta-analysis finding that exposure to potentially morally injurious events was significantly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and suicidality.” (i)

In the context of the pandemic, moral injury has become a prominent issue, deeply embedded within the ethical challenges faced by some professionals in the health sector. A considerable number of these dedicated healthcare workers have recounted feeling deserted by their peers, subjected to stigmatisation, censorship, or gaslighting for expressing concerns about COVID treatments and the safety of expedited “vaccines”.

The overhanging dread of potential repercussions, financial instability, interference from medical governing bodies and governmental authorities, and the use of derogatory labels coerced numerous healthcare practitioners in New Zealand to conform to the mainstream narrative, even if it contradicted their fundamental beliefs.

Even now, some still struggle with the internal conflict between their core principles, substantial evidence and research, and basic logic while asking themselves, “What have I done?”

It’s when a New Zealand Specialist Surgeon based in a provincial hospital strove to do the right thing for the greater good of the community despite suffering a reaction from the mRNA and then discovered via the recently published OIA of the 11,000 MoH employees exempt from mRNA jab. His story portrays the anguish of betrayal.

In an article for The Atlantic, Jonathan Moens observes, “Often, moral injury manifests as feelings of betrayal at the leaders and institutions that forced them into making these decisions in the first place, which may lead to behaviours such as substance abuse and social isolation.”

How many medical professionals, journalists and the general public are sitting in the uncomfortable position of being morally injured from overrunning their values and common sense to follow the ‘podium of truth’ as spoken by those purporting to know? The NZMC are still penalising practitioners who advised patients with an abundance of caution about the safety and effectiveness of this “vaccine.”

The general public is still being encouraged to get their boosters using fear-driven marketing strategies. All this despite evidence to the contrary. And still, the majority of our health professionals stay quiet.

What are you pretending not to know?

This continued silence, if you are a practitioner fearful of speaking out, is moral injury: staying quiet, pushing it down and away, knowing every time you administer a shot, you are undermining immunity, creating a minefield for strokes, myocarditis, infertility and what is being seen now as a resurgence of cancer.

These are the people we trust to take care of us when we need it and to offer sound advice based on their years of experience. We expect them to stay current with research and honour their commitment to the Hippocratic oath. We trust their willingness to listen, empathise and not let any unconscious bias get in the way of being the best version of themselves possible at a time when we are vulnerable.

Moral injury can manifest in different ways, including guilt, shame, remorse, anger, and a sense of moral dissonance. Individuals may feel a profound sense of betrayal or loss of trust in themselves or others. They may question their moral integrity, struggle with a loss of meaning and purpose, or experience a crisis of identity. Moral injury can also lead to social and interpersonal challenges, as individuals may struggle to connect with others or reintegrate into their communities.

Ultimately, understanding and addressing moral injury is important for the well-being of individuals and the health of societies as a whole.

Addressing moral injury requires a multifaceted approach. It involves creating supportive environments that promote ethical decision-making, fostering open dialogue about moral concerns, and providing opportunities for individuals to process their experiences.

Recognising moral injury’s unique challenges, psychologists such as Litz have been creating therapies that more directly address clients’ needs. Litz and other providers have pioneered a moral injury treatment called adaptive disclosure. Researchers at Australia’s La Trobe University and University of Queensland have developed a similar approach called pastoral narrative disclosure. The latter involves discussing moral issues with a chaplain or other spiritual adviser rather than a doctor. – Scientific American – read more here

Institutions and organisations have a crucial role to play in mitigating moral injury by prioritising ethical practices, promoting a culture of moral resilience, and ensuring adequate support mechanisms for individuals who experience moral distress. It is essential to recognise the impact of moral injury, provide avenues for individuals to voice their concerns and seek help, and work toward preventing situations that may lead to moral injury in the first place.

Safe spaces for people to air their experiences are essential, as it is recognised that a PTSD therapeutic approach is not necessarily the better support mechanism for a “soul wound”.

Reconciling and forgiving the inner self is a journey that requires deep understanding and compassion. To help personnel explore the experience of moral injury, consider guilt and shame, seek forgiveness, and reconnect with themselves, their family and their community, There is an 8-step pastoral narrative disclosure process which is having success.

The question that remains after all of this is: Are you OK?

References

(i) Williamson, V., Murphy, D., Pirkis, J., Forbes, D., & Greenberg, N. (2021). Moral injury: The effect on mental health and implications for treatment. The Lancet Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00113-9

(ii) What do we do with all this moral injury? – Practicing Excellence Knowledge Center. https://knowledge.practicingexcellence.com/what-do-we-do-with-all-this-moral-injury/

Stovall, M., Hansen, L., & van Ryn, M. (2020). A Critical Review: Moral Injury in Nurses in the Aftermath of a Patient Safety Incident. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 52(3), 320.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00619/full

Drescher et al. (2011) define moral injury as “disruption in an individual’s confidence and expectations about one’s own or others’ motivation or capacity to behave in a just and ethical manner” (p. 9). Litz et al. (2009) further describe moral injury as “the inability to contextualise or justify personal actions or the actions of others and the unsuccessful accommodation of these . . . experiences into pre-existing moral schemas” (p. 705). Shay (2014) emphasises leadership failure and a “betrayal of what’s right by a person who holds legitimate authority in a high stakes situation.” Silver (2011) speaks of “a deep soul wound that pierces a person’s identity, sense of morality, and relationship to society” (para. 6).