Table of Contents

Michael McAuley

mercatornet.com

Michael McAuley is a barrister practising in Sydney, Australia.

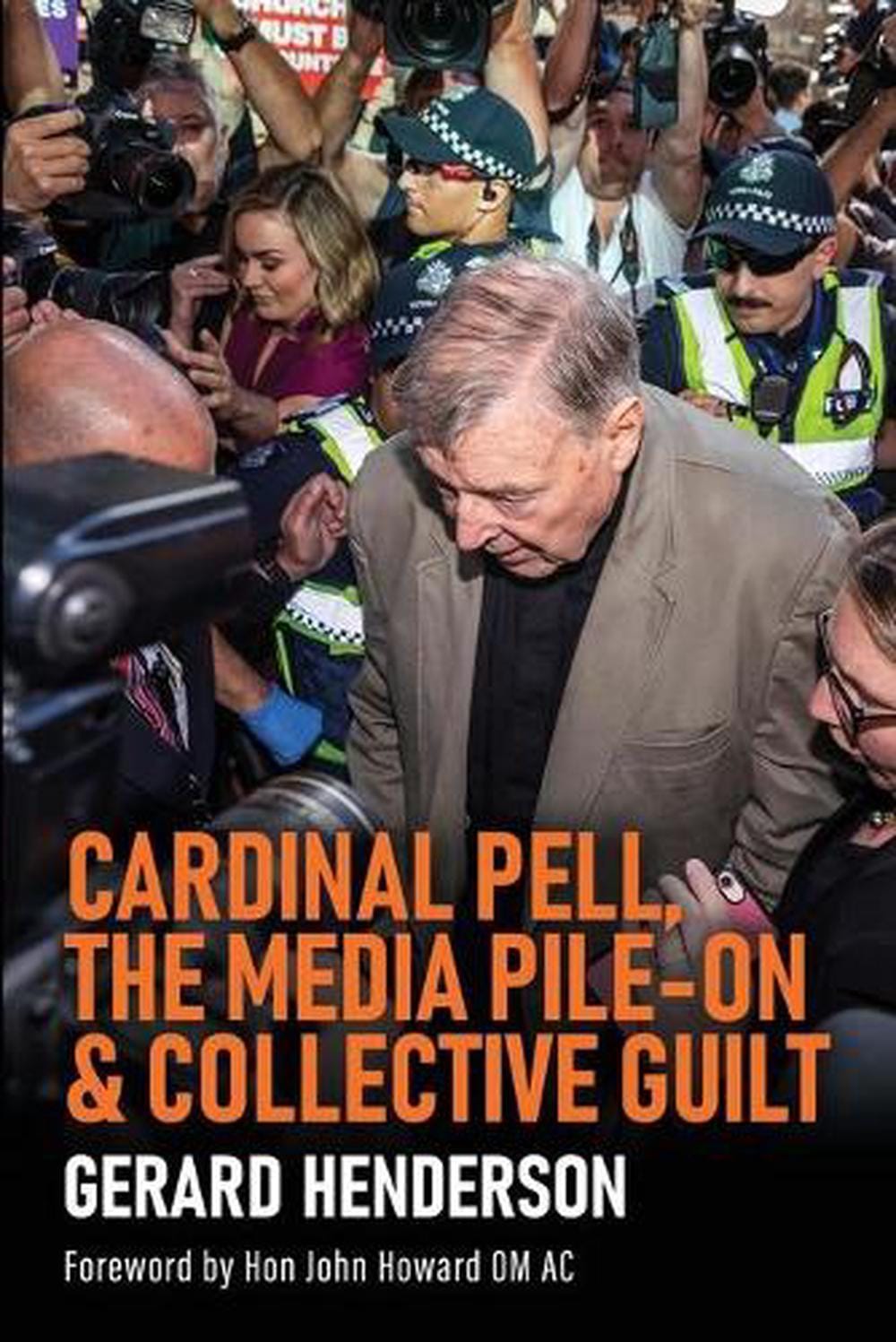

Cardinal Pell, the Media Pile-On & Collective Guilt

by Gerard Henderson. Connor Court. 2021. 468 pages

John Howard’s Foreword to Gerard Henderson’s Cardinal Pell, the Media Pile-On & Collective Guilt says as much about the former Prime Minister’s decency as about Pell:

“I never believed the charges ultimately brought against the Cardinal. That was based on my assessment of him as a man and the implausibility of the offences having taken place within the circumstances which were alleged. I felt that justice had been served when the full bench of the High Court of Australia unanimously upheld his appeal and quashed the original convictions.”

High Court Decision

The legal effect of the High Court decision is not merely that the prosecution failed to prove its case. Cardinal Pell is innocent of the crimes with which he was charged. In R v Darby Justice Lionel Murphy in the High Court said an acquittal is a finding of innocence. An accused is taken as entirely innocent of any charge of which he has been acquitted. Justice Murphy’s comments are consistent with the authorities.

The nub of the High Court decision is expressed succinctly in the headnote in the Commonwealth Law Reports:

“…notwithstanding that the jury found the complainant to be a credible and reliable witness, the evidence as a whole was not capable of excluding a reasonable doubt as to Cardinal Pell’s guilt. Accordingly, there was a significant possibility that an innocent person had been convicted, because the evidence did not establish guilt to the requisite standard of proof.”

There were over 20 witnesses whose evidence was not challenged and whose evidence placed Cardinal Pell on the steps of St Patrick’s Cathedral, chatting to worshippers, at the time of the alleged commission of four of the five alleged offences:

Upon the assumption that the jury assessed the complainant’s evidence as thoroughly credible and reliable, the compounding improbabilities caused by the unchallenged evidence of other witnesses (as to Cardinal Pell’s movements after the Mass, Cardinal Pell always being accompanied within the Cathedral, and the “hive of activity” in the priests’ sacristy after Mass) nonetheless required the jury, acting rationally, to have entertained a doubt as to Cardinal Pell’s guilt.

As to the fifth charge, the offence was said to have occurred during the course of a procession after Mass. Victoria Police failed to interview the participants in the procession, no doubt because the witnesses would have said, if asked, that they had observed nothing untoward. Having read the decision of both the Victorian Court of Appeal, and the decision of the High Court, it seems to me the prosecution of Cardinal Pell ought never have been commenced. There was insufficient evidence.

Inquiry

There should be an inquiry into why the prosecution was commenced at all – and the inquiry ought to include the conduct of the police, the conduct of the media, evidentiary provisions in Victorian law restricting cross-examination of a complainant, the lack of availability of a judge-alone trial in Victoria. The miscarriage of justice involved in the wrongful prosecution of Cardinal Pell is but an aspect of reasonable concerns about Victoria Police, the Victorian courts, and the right of Victorians to a fair trial.

It is not feasible to conduct an inquiry into the McClellan Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, but there is sufficient information on the public record to reasonably conclude the Royal Commission came to conclusions about Cardinal Pell not grounded in evidence. There are broader concerns about the methodology of the Royal Commission, in particular, what appears to be its animus towards religious institutions, and its failure to adequately investigate police responses to complaints of child sexual abuse, as well as misconduct in government-run institutions.

“Conservative”

A preliminary to any assessment of the Pell saga is to ask: is it accurate to regard Cardinal Pell as a “conservative”? The term “conservative” (like the terms “left” and “right”) is used in politics. Even in politics, “conservative” has very little defined meaning, at least in the context of political systems around the world, in different historical periods, and having regard to different approaches to political philosophy.

Does the term “conservative” enhance an understanding of Cardinal Pell, or is “conservative” a boo word or a word of endearment, but in any case an impediment to serious analysis? Depending on who is using the term “conservative”, it can be a term of abuse, of adulation, a slogan, involving an absence of thought, a simplification ignoring the complexity of situations and issues.

Reformer

Cardinal Pell, upon his appointment as Archbishop of Melbourne, got rid of over 30 priests, established the Melbourne Response to address sexual abuse (a first in Australia, and amongst the first such responses in the world), reformed the Melbourne seminary, established the John Paul II Institute for Marriage & Family and enhanced St Patrick’s Cathedral.

Cardinal Pell adopted a similar approach in Sydney, re-establishing the university apostolate, reforming the seminary, encouraging the establishment of Campion College, encouraging the establishment of a Sydney campus of the University of Notre Dame, encouraging reform of the Australian Catholic University, reorganising Archdiocesan finances, establishing Polding House as an administrative centre for the Archdiocese, establishing modern management within Archdiocesan bureaucracies. As the Vatican’s Prefect of the Economy, Cardinal Pell addressed financial corruption, evoking very strong opposition.

Catholic Tradition

Cardinal Pell engaged with the world, enhancing the Church’s involvement in the media, and intellectual life, outspokenly addressing issues from a Catholic perspective, and encouraging Catholic intellectuals such as Professor Tracy Rowland who has gone on to become a theologian of international significance.

Cardinal Pell is a reformer, albeit adhering strongly to the Catholic tradition. Cardinal Pell accepts and defends traditional Catholic beliefs highlighted in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Cardinal Pell’s unashamed embrace of the Catholic tradition does provide an explanation for much of the antagonism to him, both within the Church, and without.

Gerard Henderson rightly highlights the antagonism to Cardinal Pell from those who seek to receive Holy Communion while, at the very time of receiving Communion, promoting a gay agenda (the Rainbow Sash Movement).

Right to a Fair Trial

The right not to be condemned without a fair trial and the right to a fair trial are what the rule of law is all about. Respect for the rule of law is an aspect of respect for the common good, something we all should be concerned about. We are all bound by law, no matter who we are.

The right to a fair trial is particularly important for high-profile controversial persons, for the down and out, for the unpopular, for the average person, for those who have nothing – and for you and me. Anyone can be the subject of a false allegation. Not every allegation is true.

The committal hearing before the Magistrates’ Court, and the County Court trials were wild affairs as Cardinal Pell, his several advisers and legal team, despite police protection, were frequently abused and jostled by persons outside the court.

Of the 26 offences with which Cardinal Pell was originally charged by Victoria Police, only five went to trial in the County Court. The remainder were either dismissed or abandoned.

Forensic Disadvantage

The most important fact about the two trials of Cardinal Pell is that there was a gap of over 20 years between the alleged offences and the trials.

Cardinal Pell was at significant forensic disadvantage in the County Court: the delay in reporting prevented adequate investigation; the memory of many witnesses had deteriorated with the years; some witnesses were elderly, or even, in the case of the former Dean of the Cathedral, Monsignor McCarthy, in a nursing home, incapable of giving evidence; the passage of time made it difficult to test the complainant’s evidence, given his lack of recall of specific detail; a second alleged victim was dead (although before his death he had denied being sexually abused).

The defence was impeded because the trial judge ruled against the defence questioning police witnesses on the basis that the charges were brought as part of a Get Pell Campaign, and against cross-examination of the complainant on his prior psychiatric and criminal history. There was no effective means of preventing jurors trawling the internet for material which may have influenced their verdict.

Shortly before the first of the Pell trials, on 3 July 2018, the then Archbishop of Adelaide, Philip Wilson, was found guilty by Magistrate Robert Stone of covering up child sexual abuse. On 6 December 2018, an appeal by Archbishop Wilson to the District Court was successful and his conviction was quashed.

Two Trials

On 20 September 2018 the first jury was discharged after failing to reach a verdict. Between the first trial and the second trial Prime Minister Scott Morrison issued a National Apology to Victims and Survivors of Institutional Sexual Abuse. While one can understand the political imperative behind the Apology, it did not enhance a calm determination of the allegations by the second jury.

At the retrial, the second jury, after deliberating for almost four days, reached guilty verdicts on all five charges. While each of the two trials were conducted in secret as regards the public, the sentencing was screened around the world. Secrecy breeds injustice.

Appeal

Cardinal Pell was unsuccessful in his appeal to the Victorian Court of Appeal, his appeal being dismissed by two judges, with a third, Justice Weinberg, a criminal specialist, dissenting. Justice Weinberg’s dissent became the basis for the unanimous decision of the seven judges of the High Court to uphold Cardinal Pell’s appeal.

Lawyers

Cardinal Pell had the very best of legal representation, Robert Richter QC on committal and at trial, and Brett Walker SC on appeal. There were some very fine lawyers advising in the background. One can only pity an unpopular defendant, the object of media hysteria, who does not have such access to good legal representation!

Following Cardinal Pell’s successful appeal and acquittal in the High Court, the Premier of Victoria, Daniel Andrews, whose government had appointed a number of key players in the ultimately unsuccessful Pell prosecution, said:

“I make no comment about today’s High Court decision. But I have a message for every single victim and survivor of child sexual abuse. I hear you. I believe you.”

Nothing here about the right to a fair trial.

Media

Gerard Henderson provides a wealth of detail to demonstrate that many in the media sought to condemn Cardinal Pell without a fair trial. Many of the journalists involved in the Get Pell Campaign were activists rather than reporters. The ABC led the pack but there were other media organisations and other journalists involved in the Get Pell Campaign. There was an ongoing media push against Cardinal Pell, who ended up wearing blame for all sexual abuse in the Australian Catholic Church. This was ironic given Cardinal Pell’s role in largely bringing sexual abuse to end.

The media campaign against Cardinal Pell was inconsistent with the right to a fair trial. Gerard Henderson’s chapters 6, 7 and 8, dealing with the media pile-on, are particularly significant, given Henderson’s long experience in analysis of the Australia media, a subject of which there is regrettably far too little consideration. Henderson argues that the media pile on against Cardinal Pell led to a situation where no jury could be expected to assess the evidence with an open mind, no matter how much the jurors tried.

Victoria Police

Gerard Henderson demonstrates Victoria Police abandoned normal police practice in pursuit of Cardinal Pell. Operation Tethering directed to Cardinal Pell was established in 2013 without any complaint, at a time when there was gathering public concern at the failure over many years of Victoria Police to investigate allegations of child sexual abuse. Henderson says Victoria Police went looking for a crime before any crime had been complained of. Victoria Police eventually resorted to advertising for a complainant, nominating the dates Cardinal Pell was Archbishop of Melbourne. Contrary to normal police practice, the police investigation failed to obtain statements from many relevant witnesses.

Interestingly, Victoria Police Commissioner Carl Ashton denied the investigation was established before there was any complaint, a denial inconsistent with evidence in the County Court. The police engaged in a media strategy calculated to undermine Cardinal Pell’s defence. On three occasions, the then Victorian Director of Public Prosecutions returned the police brief, leaving the decision to prosecute to Victoria Police.

According to Gerard Henderson the police investigation was in the context of hostility between Victoria Police under Commissioner Carl Ashton and the Archdiocese of Melbourne. Victoria Police were engaged in a Get Pell Campaign.

Down Memory Lane

Gerard Henderson highlights the risks of flawed memory in relying on uncorroborated evidence of events said to have occurred many years ago. He points to an article by Justice Peter McClellan in the Australian Law Journal, the contents of which appear to have slipped McClellan’s mind when he chaired the Royal Commission. McClellan’s article provides a detailed analysis of the difficulties associated with memory evidence, particularly as to historic events.

To call a person a “victim” when there has been no formal process to determine whether an allegation is soundly based, particularly where the allegation is historical, is not an exercise in justice.

Gerard Henderson analyses the flawed nature of “collective guilt”, the notion that someone should be condemned for actions they never personally committed, simply because they belong to a group (Catholic bishops and religious leaders).

Royal Commission

Gerard Henderson raises serious questions about the McClellan Royal Commission which conducted significant “hearings” prior to the Pell trial. When acting as Chair of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Justice Peter McClellan was not acting as a judge. The Royal Commission was not a court-there were no rules of evidence, no requirement as to the provision of particulars, no obligation to provide reasons for particular decisions, no right of appeal.

The Royal Commission comprised six members, the majority of whom were not practising lawyers. One Royal Commissioner was a former Queensland Police Commissioner, odd given that police (including the Queensland police) commonly did not pursue complaints of child sexual abuse, and this was a reasonable matter for inquiry by the Royal Commission. Although the subject matter of the inquiry was contentious, and one would expect different views to emerge amongst the Royal Commissioners, there were no recorded dissents on any issue.

Amongst Henderson’s complaints about the Royal Commission is that the CEO Peter Reed sometimes interfered in public debate, that the emphasis on Catholic offending was not supported by research, that the Royal Commission focused on religious schools, largely ignoring similar abuse in non-religious (usually state-run) schools, that both Peter McClellan and counsel assisting Gail Furness SC demonstrated antipathy to Cardinal Pell, and that the “findings” against Cardinal Pell were not justified by the evidence.

According to Henderson, McClellan effectively “convicted” Cardinal Pell – at least in the eyes of large sections of the public – in the absence of evidence – while, on occasion, denying him due process.

Not commented on by Gerard Henderson, but to my mind one of the most bizarre aspects of the Royal Commission was the calling of Bishop Ronald Mulkearns to give “evidence”. At the time Bishop Mulkearns was incapable of giving evidence, given his mental state. Bishop Mulkearns died not long after giving “evidence”, thwarting an attempt to call him a second time.

A second bizarre action was the taking of “evidence” from Gerard Ridsdale, a serial predator, with a long history of manipulative activity. The only reasonable response to Ridsdale’s “evidence” was to view it with considerable caution.

Best and Worst

The two trials and the two appeals of Cardinal Pell show the Australian system of law at its best and at its worst, Australian opinion leaders at their best and at their worst. Amongst the best is Gerard Henderson who has produced a book which is interesting, easy to read, replete with common-sense — and which demonstrates intellectual courage, and willingness to bear unpopularity in the pursuit of the truth.

Prison Journal

Shortly before the release of Gerard Henderson’s Cardinal Pell, the Media Pile-On and Collective Guilt, Cardinal Pell released the third and final version of his Prison Journal. In my opinion, this is a significant work of religious literature. A condensation of the three-volume Prison Journal might sieve out the perennial from the mundane, presenting the perennial in shorter and more accessible form to readers not requiring to be convinced of the coarseness, the boredom, the unpleasantness, the petty tyranny of life in Victorian gaols.

The nun who sold me my Prison Journal volume 3 said she used it for her prayer. The subject is Cardinal Pell’s prison life from the perspective of the Prayer of the Church, the Divine Office, and in the context of a continuing conversation with the many and great thinkers of Western civilization.

While there is much in the Prison Journal which is transient, there is much which is transcendent — forgiveness; forbearance; acceptance of suffering; the life of a Christian which can be led anytime, anywhere, in any circumstances; the ever-present possibility of prayer; the imitation of the life of Jesus of Nazareth.

So, between Gerard Henderson and George Pell, there is a chink of light. Eventually the High Court got it right. And many ordinary Australians, despite the mob, stuck up for the underdog, stuck up for the right to a fair trial, something which should be accorded to anyone, and everyone.