Table of Contents

Jen Webb University of Canberra, Alice Gorman Flinders University

Carol Lefevre University of Adelaide, Dennis Altman La Trobe University

Hugh Breakey Griffith University, Julian Novitz Swinburne University of Technology

Matthew Ricketson Deakin University, Oscar Davis Bond University

Peter Mares Monash University, Tom Doig The University of Queensland

Tony Hughes-d’Aeth The University of Western Australia, Alexander Howard, Tanya Latty University of Sydney

Edwina Preston, Julienne van Loon, Nick Haslam The University of Melbourne

Anna Clark, Carl Rhodes, Heidi Norman, Wanning Sun, University of Technology Sydney

We asked 20 of our regular contributors to nominate their favourite books of the year. Their choices were diverse, intriguing and sometimes surprising. Whether you’re looking for something relaxing or stimulating, educational or enchanting, this selection is a great way to plan your summer reading – or simply add to your bedside book tower.

Edwina Preston

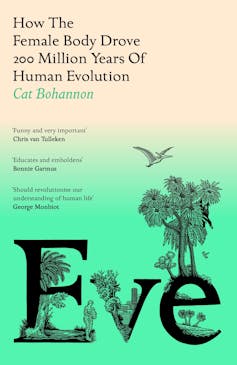

My best book of 2023 is US essayist Cat Bohannon’s Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Evolution (Hutchinson Heinemann). The tenor (and overall thesis) of Bohannon’s female-centred evolutionary history is encapsulated in a rewriting of the opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The marvel, in Bohannon’s version, and in her book overall, is not the evolutionary moment in which a tool is deployed as a battering weapon, but the quiet assistance of one pregnant and labouring woman by another. Midwifery and gynaecology: these are the evolutionary wonders that have allowed us to thrive as a species.

Bohannon’s book is less about correcting the evolutionary record than writing a cogent new evolutionary story altogether.

– Edwina Preston is a PhD candidate in the School of Culture and Communication, Melbourne University. Her novel Bad Art Mother was shortlisted for the 2023 Stella Prize.

Tony Hughes-d’Aeth

I’m not sure how I missed the work of Anne Enright. She didn’t exactly fly beneath the radar. But I read Enright’s The Wren, The Wren (Jonathan Cape) and was completely entranced. It is the best perspectival family novel I’ve read since Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections (2001). It offers a frank, feminine interiority that was often heartbreaking and occasionally hilarious. The book has a complex, loving hatred of men that was utterly fascinating.

Other books that really impressed me were Alexis Wright’s latest novel Praiseworthy (Giramondo), and Nicholas Jose’s fine novel The Idealist (Giramondo), set in the political intrigue of East Timor’s independence struggle.

– Tony Hughes-d’Aeth is the Chair of Australian Literature at the University of Western Australia.

Oscar Davis

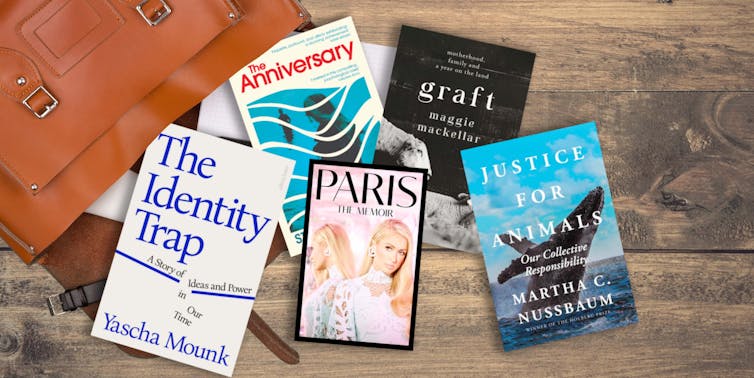

One of the greatest moral challenges of today is overcoming our deeply rooted moral estrangement from the natural world and motivating meaningful action in the face of environmental crises. In her book, Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility (Simon & Schuster), renowned philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum argues we require an ethical awakening that will lead to a new revolution in animal rights and law.

Her philosophical analysis of the past and future of environmental ethics decentres human interests and redirects our moral attention to the wondrous particularities of the lives of animals. Nussbaum demonstrates how the flourishing of the natural and social worlds is a collective duty.

– Oscar Davis is Indigenous Fellow and Assistant Professor in Philosophy and History, Bond University.

Julienne van Loon

Simone Lazaroo’s sixth novel, Between Water and the Night Sky (Fremantle Press), opens with the narrator, Eva, sitting in a darkened hospital room and holding the still-warm hand of her recently deceased mother.

Lazaroo’s autofictional work is a subtle, contemplative reflection on migration, bicultural marriage and the awful power of silence, written with the lightly playful yet sharply observant approach to Australian life that has come to characterise her work as a novelist.

The mental health of the aged is a key theme, but this book left me contemplating larger questions too: what is a life well lived? A tender and wise elegy, it deserves a broad readership.

– Julienne van Loon is associate professor in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Melbourne.

Wanning Sun

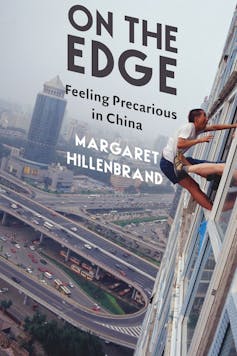

Written by a cultural studies academic, Margaret Hillenbrand’s On the Edge: Feeling Precarious in China (Colombia University Press) offers a new way of writing about social marginality and banishment as experienced by China’s underclasses – through the analysis of cultural and art forms.

Hillenbrand is as searing and uncompromising in her critique of the power of the state and neoliberal market as she is sensitive and compassionate to rural migrant labourers. The book is definitely not “China for Dummies”, nor will it leave you with a feelgood aftertaste. But you’ll be rewarded with a deeper appreciation of the moral complexity that is essential to understanding China.

– Wanning Sun is a professor of Media and Cultural Studies at University of Technology Sydney.

Matthew Ricketson

If you haven’t already, dive into Mick Herron’s spy storyworld. His Slow Horses (John Murray) series of eight novels updates (and, to many, improves on) John Le Carré.

Where tradecraft is central to Le Carré’s bleak cold war novels, the slow horses are agents sent to MI5’s knackery, known as Slough House, and overseen by Jackson Lamb, a character as memorable as George Smiley but utterly different. Marinated in whiskey, shrouded in stale cigarette smoke, he’s as foul-mouthed as the fart-fugged air in his airless office. “Off you fuck”, he barks to end meetings of his hapless charges.

Funny, cynical, beautifully written and unputdownable.

– Matthew Ricketson is Professor of Communication, Deakin University.

Anna Clark

My pick for this year is a beautiful work of memoir by Maggie MacKellar, Graft: Motherhood, Family and a Year on the Land (Hamish Hamilton). Writing about life on her sheep farm in southeast Tasmania over a year, Mackellar gives an account of precarity caused by drought and climate change, as well as the beauty of our attachments to place.

Alongside this narrative of the farm itself is a moving family story, Mackellar’s own, of childhood, motherhood and loss. It’s beautifully written without being sentimental, inviting us into her curious and gentle inner thoughts that weave and wend across place and time.

– Anna Clark is a professor at the Australian Centre for Public History, University of Technology Sydney.

Tanya Latty

Adam P. Karremans’ Demystifying Orchid Pollination: Stories of Sex, Lies and Obsession takes readers on a journey into the wild world of orchid pollination. From sexually deceptive orchids that entice amorous male wasps by mimicking the look and smell of the female insects, to orchids that intoxicate their pollinators with narcotic-laced nectar, orchids have evolved fascinating techniques to entice – and trick – animals into helping them reproduce.

The book is enhanced by the innovative use of QR codes linking to videos showing some seriously incredible insect-orchid interactions. The fascinating video content and beautiful photographs make for a wildly entertaining multimedia experience. Chapters are named after famous songs (“I put a spell on you”, “Original Prankster”), which adds to the book’s sense of wonder and fun. But make no mistake – this book contains serious science written in a way that will appeal to biologists and lay people alike.

– Tanya Latty is an associate professor in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences at the University of Sydney.

Nick Haslam

Patrick Weil’s The Madman in the White House (Harvard University Press) has it all: political intrigue, momentous historical events, a charismatic central character who mixed with Churchill, Stalin, Hemingway and Picasso, a cameo by Sigmund Freud, an astonishing discovery in the archives and a champagne-drinking bear.

The story of US diplomat William Bullitt and his infamous psychobiography of Woodrow Wilson – to Freud “the silliest fool of the century if not all centuries” – the book excels as history, character study and intellectual thriller. Weil’s assertion that “democratic leaders can be just as unbalanced as dictators” is more apt now than ever.

– Nick Haslam is Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne.

Heidi Norman

I was delighted to read Graham Akhurst’s debut novel Borderland (UWA Publishing). Akhurst explains that his interest in writing Borderland was to write to and for his younger self.

The novel is set in Brisbane and the two lead male and female characters (Jono and Jenny) are vitally entwined. Jono, an Aboriginal boy from a single-mother household, casts a nervous and anxious gaze on the world around him, confined as it is to a private school and life in outer suburban Brisbane. We see and experience the world through his inquiring and sometimes wounded eyes. Jenny, in contrast, starts out far more confident about herself and the world she draws upon.

There are two key themes explored in the novel. One is identity, not of the clunky salvation trope, but rather through understanding, with attention and care, how an Aboriginal boy navigates life when carrying the significant burden of being expected to know, in a fixed, linear way, who he resolutely is. This exploration reveals the fluidity of identity as a process of becoming: perhaps through meaningful relationships and experiencing your Country.

The second theme is the challenge and dilemma Aboriginal communities encounter navigating survival – when extractive industrial capitalism is underway on your land – alongside the embodied responsibility to Country. It’s what we might think of as Aboriginal modernity.

All over Australia, Aboriginal communities are forced to engage in the Faustian bargain at great risk and cost. Both these themes are difficult to communicate, let alone to the intended reader of this book: a 15-year-old Aboriginal boy. Inspired by the work of acclaimed writer Alexis Wright, Akhurst’s Indigenous realism brings them to dramatic effect.

– Heidi Norman is Professor and Associate Dean in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, and a researcher in the field of Australian Aboriginal political history.

Julian Novitz

New Zealand novelist Catherine Chidgey has been on an incredible creative roll, with three critically acclaimed novels published in the space of just four years.

Her latest, Pet (Europa), follows the development of an increasingly disquieting relationship between its 12-year-old narrator Justine and her charismatic teacher, Mrs Price.

The novel is a superbly executed slow-burn thriller, which builds out of the stifling isolation of 1980s New Zealand life, and the disorienting competitiveness and paranoia Mrs Price cultivates in her classroom.

– Julian Novitz is Senior Lecturer, Writing, Department of Media and Communication, Swinburne University of Technology.

Dennis Altman

John Addington Symonds and Henry Ellis were significant pioneers of sexology in the late 19th century, who together wrote Sexual Inversion. Tom Crewe has constructed a fictional account of their lives, The New Life (Chatto & Windus), acknowledging it should not be read for historical accuracy. As he states, “Symonds died in 1893 and this novel begins in 1894.”

Both men marry, Symonds to hide his homosexuality, Ellis because he believes in the emancipation of women and encourages his wife to have a lesbian relationship. Historically inaccurate, yes, but it captures brilliantly the sexual politics of an era overshadowed by the Oscar Wilde scandal and the origins of the suffragette movement.

– Dennis Altman is Vice Chancellor’s Fellow, Latrobe University.

Alice Gorman

Paris Hilton’s memoir (HarperCollins) is a surprisingly good read. A focus of the book is her time at a reform camp in Utah, at which inmates were subjected to brutal punishment to make them socially compliant. Over the past few years, Hilton has been vocal in support of other survivors of the US “troubled teen” industry.

Her accounts of not being believed will resonate with the abused and powerless, no matter their social status. Although the book is ghostwritten by Joni Rodgers, Hilton comes across as thoughtful and empathetic. It’s too easy to dismiss this memoir as just celebrity posturing. Sometimes it’s worth putting aside preconceptions for a glimpse of the person behind them, however imperfectly.

– Alice Gorman is Associate Professor, Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University.

Alexander Howard

Diane Williams is interested in formal constraints, and in seeing how much one can do with seemingly very little. Her fans consider her a living avant-garde icon and the godmother of flash fiction. The short stories in Williams’ eleventh collection – I Hear You’re Rich (Scribe) – are some of her very best.

Alluring and allusive, the 33 beautifully wrought literary miniatures in this volume – the shortest of which is a single sentence of 23 words – are characteristically attuned to what Williams describes as “those exigencies, calamities that underpin everyday life”. Taken together, these distinctive – and sometimes surprisingly comedic – stories confirm Williams is indeed one of the most important US writers working today.

– Alexander Howard is Senior Lecturer in English and Writing, University of Sydney.

Tom Doig

Bret Easton Ellis’ latest novel The Shards (Swift Press) is a revelation. The ageing enfant terrible audaciously mashes up his own back catalogue and personal mythology, combining the Rayban-dangling teen horniness of Less Than Zero with the gore, paranoia and indeterminacy of American Psycho.

“Bret” drifts through high school in early 1980s Los Angeles, ignoring his girlfriend, lusting after hot guys and spiralling into drug- and writer’s-block-fuelled psychosis; there’s also (at least) one serial killer. The result is all kinds of queer: somehow more emotionally grounded, yet also more untouchably arch, than anything he’s written before.

Plus, there’s a next-level reference to Al Stewart’s 1970s novelty hit Year of the Cat.

– Tom Doig is Lecturer in Creative Writing, University of Queensland.

Carl Rhodes

Susan Neiman’s Left is not Woke (Polity) provides a much-needed intervention into the banality of political debates over “wokesim”. In an age of unintelligent political polarisation, Neiman argues convincingly that true progress requires a commitment to a deep solidarity and universal justice – a commitment that both politically correct divisiveness and reactionary woke-baiting undermine.

The book offers a way out of the dead-end thinking that confines politics to simplistic oppositions – affirming, in Neiman’s words, “a belief in the possibility of progress”. Aspirational yet realistic, Neiman’s book urges the left to get back to the primary project of social change and economic justice.

– Carl Rhodes is Dean and Professor of Organization Studies at UTS Business School.

Carol Lefevre

In Stephanie Bishop’s addictive fourth novel, The Anniversary (Hachette), her deceptively calm narrator, the writer J.B. Blackwood, books a cruise with her husband Patrick.

Unknown to Patrick, a charismatic filmmaker and J.B.‘s one-time professor, his younger wife is about to receive a glittering literary prize. As they board the ship, the reader is aware of impending tragedy, and the storm in which Patrick will be lost overboard. After being questioned by Japanese police, and identifying her husband’s body, J.B. presses on to New York and the awards ceremony.

If uncertainty around Patrick’s fatal plunge hadn’t held me, J.B.’s searing insights into the publishing industry would have kept me turning the pages. Bishop probes the complexities of shared creative lives, the consequences of desire, the long reach of childhood trauma, and the sometimes casualty-strewn path carved out by ambition.

– Carol Lefevre is Visiting Research Fellow, Department of English and Creative Writing, University of Adelaide.

Hugh Breakey

For me, 2023’s best book was Yascha Mounk’s The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time (Allen Lane). Mounk’s book clearly and accessibly explains, explores and critiques an increasingly influential type of progressivism – one that steps away from traditional leftist concerns with class and economic inequality to focus on people’s identities (like race and gender).

Mounk acknowledges this worldview’s many initial insights. However, he argues that these have ultimately created a “trap” that lures in those committed to social justice, only to drive them to a divisive and self-defeating tribalism, intolerance and separatism.

– Hugh Breakey is Deputy Director, Institute for Ethics, Governance & Law and President, Australian Association for Professional & Applied Ethics, Griffith University.

Peter Mares

The best books I read in 2023 were published in 2022, but I recommend both as essential reading in the wake of the No result at this year’s Voice referendum.

Kim Mahood’s Wandering with Intent (Scribe) is a collection of essays about art, culture, mapping, environment and intercultural (mis)understandings, drawing on Mahood’s long-term collaborations with First Nations peoples in remote Australia over many decades.

Dean Ashenden’s Telling Tennant’s Story (Black Inc.) recounts the unsettling history of the great Australian silence regarding the reality of our violent colonial past. In very different ways, both books advance the cause of truth telling and go to the troubling heart of who we are as a nation.

– Peter Mares is Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, School of Media, Film and Journalism, Monash University and a moderator with the Cranlana Centre for Ethical Leadership at Monash University.

Jen Webb

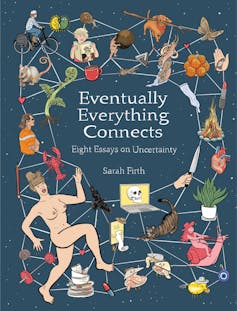

Sarah Firth’s Eventually Everything Connects: Eight Essays on Uncertainty (Allen & Unwin) is a sequence of graphic essays about the activities that fill one’s days (and nights), all the anxieties and uncertainties, and the everyday – often dada – moments in a world that whirls on, beyond our control.

The “everything” and the “uncertainty” of the title have a lovely immediacy, with beautifully rendered illustrations, a strong sense of voice and presence, and a sometimes wry, sometimes laugh-out-loud humour.

Reading it felt like a conversation with a remarkable friend, tracing with her all the lines of her thinking, to a kind of understanding that maybe, in some hard-to-articulate way, everything really does connect.

– Jen Webb is Executive Dean, Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.