Table of Contents

Francis Forde

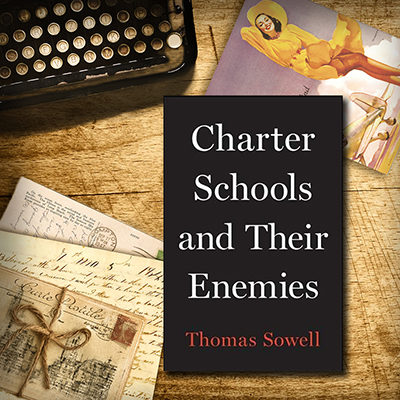

I was filled with equal parts excitement and disappointment upon receiving Thomas Sowell’s latest book Charter Schools and Their Enemies. Sowell is known for his dauntingly long ventures into historic migratory patterns, cultural differences, and economic problems. Although many of his books strain to five hundred pages, I was saddened to find that this book drops off at around one hundred and thirty. In part, it was a sad occasion because Sowell recently celebrated his 90th Birthday, and so the welcomed arrival of his new book was paired with a poignant realization that it may be the last he pens.

Sowell grew up poor in Harlem and later went on to graduate from Harvard and receive a PhD in economics from Chicago. Since then, he has published over 50 books and spent more than 60 years challenging the ideological dogma which inflicts most discussions of policy and politics today. For anyone unfamiliar with Sowell’s work, his parsimonious approach to writing will be a treat. Where simplicity is on offer, Sowell labors to provide it – preferring to ground his ideas in language that is understandable to all. This preference for no-nonsense prose is part of the reason that he is so widely revered. Now, granting all that, I believe this book has taken one of his core dictums to the extreme – that hard facts and data are superior to feelings and intentions. In the quest for hard evidence to substantiate his claims, Sowell has filled half of this book with weighty grayscale data tables. Though useful, I must admit, they are a little menacing.

Anyway, now for the book. Charter Schools and Their Enemies performs several important tasks. It provides a data-driven argument highlighting the performance of charter schools, it unpacks the factors leading to their success, and it dissects many popular responses which try to undermine their credibility. I will try to capture here some of the value on offer within the book, and showcase why it deserves some space on your bookshelf.

Sowell spends the first fifty pages getting the facts straight. By drawing on data from both traditional schools and charter schools, he shows that charter schools are far superior in performance for economically disadvantaged students. His approach here is similar to the results section of a scientific publication, which I imagine gives the impression that it must be excruciatingly dull. In so far as following an aged man as he summarizes statistics tables is boring, then reading this section should be nothing more than that. But as I ventured through the first dozen pages, the feeling of boredom failed to surface. Instead, I was simply stunned to encounter the overwhelming amount of data that Sowell has managed to squeeze between the covers – very consequential data to boot.

In conducting his analysis, Sowell compares traditional public schools and charter schools on a set of English and Mathematics tests. But of course, before doing so, he had to first identify some reasonable set of selection criteria to decide which schools to include in his analysis. To circumvent accusations of cherry-picking, Sowell stipulates that:

- Classes must contain a similar ethnic makeup of students.

- Classes must be delivered in the very same building; and

- Both schools must have one or more classes at the same grade level (allowing for direct comparisons to be made).

Given the large number of classes meeting these criteria, further narrowing was required. This led to the identification of five networks of charter schools. Each of these had classes in at least five different buildings, and also met the criteria above. The subsequent analysis, comparing charter school results to those of traditional public schools, is simply shocking.

For example, in summarizing the 2017-2018 results from the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP), Sowell writes “a majority of KIPP charter students scored at Level 3 (“proficient”) or above on the English Language Arts test in 10 of their 14 grade levels” (p.9). In contrast, he continues “A majority of the traditional public school children in these same five buildings scored at Level 3 (“proficient”) or above in just one of their 20 grade levels” (p.9).

More astoundingly, when looking at the bottom end of performance, Sowell finds that none of the KIPP classes examined had 40% or more of their students falling within the category of level 1 (“well below proficient”), whereas 11 out of 20 of the traditional public schools had 40% or more scoring that low (p.12). Regarding mathematical competency, even larger disparities were present. KIPP charter students scored at level 3 (“proficient”) or above in 12 of the 14 classes. This creates a depressing contrast as, among the traditional public school classes, only one in 20 had a majority of students at level 3 or above (p.12).

Throughout the subsequent pages, we see a continuation of this trend. Time and time again we find that the proportion of traditional public school students falling into the lowest performance category is some multiple of (and in some cases seven times as many as) the number of charter students performing that poorly. We also find that the total number of charter classes with a majority of their students scoring at proficient or above is much higher than in traditional public schools. Given that these comparisons control for the ethnic and socioeconomic background of the students, that the tests used are standardized and conducted statewide, and that the classes take place in the very same buildings, the reader is left puzzled. What in the world could account for such radical differences in academic performance?

In the second portion of the book, we follow Sowell as he unearths the main factors which he believes account for these performance gaps. As a very simplified overview, he makes the case that charter schools are superior because they:

- Have higher disciplinary standards and greater readiness to enforce rules.

- Hold teachers to account for the results of their students (to a greater degree).

- Care less about whether staff have state-approved certifications.

- Have more freedom to release staff who are not performing well; and

- Have lower rates of unionization.

I will try to add some flesh to these points, as a taster for what Sowell offers at length within the book.

Sowell argues that traditional public schools are less active in their application of disciplinary standards. This seems to be explainable by the intersection of two motives – one well-intentioned, the other not so much. On the one hand, we have the pursuit of social justice. This tries to remove the disparate rates of punishment dished out to children belonging to different ethnic groups. For example, black students were found to be two-and-a-half times as likely to be disciplined when compared to whites, and five times as likely compared to Asians (p.105). If this disparity is one of detection rates, caused by stereotyping and unequal surveillance, then the pursuit to diminish this disparity would be a laudable goal. However, if disorderly behavior is truly carried out at different rates, and you cannot increase bad behavior for the other groups, then only one option remains to remove this despicable statistic. You must simply stand by and let those destructive students wreak havoc in the classroom. Lower punishment levels, irrespective of what it does for the education of the surrounding students, will at least make the school look more equitable.

On the other hand, Sowell makes the case that there is also a financial motive for lowering punishment – especially of the harsher variety. Bluntly stated, the fewer people you expel, the more people on your school roll. The more people on your school roll, the more teachers you require (or retain), and the more funding you receive. And given that most public school teachers are unionized, this will result in more fee-paying union members. To then come full circle, you can see how this cycle would be reinforced by unions lobbying to reduce punishment – of course, under the guise of compassion for the students.

To highlight the culpability of unions for the failure of American education, Sowell quotes one union head who states that, “When schoolchildren start paying union dues, that’s when I’ll start representing the interests of schoolchildren” (p.56). It is a sad but honest acknowledgement of where union interests lie. Since charter schools threaten to reduce the number of jobs for unionized teachers, ultimately decreasing union revenues, you can now imagine how determined they are to stop their spread. Whether this be by lobbying for regulations to limit the number of charter schools allowed per state, or by refusing to let them buy unused school buildings. Whatever the route, it becomes clear why the espoused concern for improving schooling for disadvantaged students has failed to materialize in the face of financial incentives moving in the opposite direction.

As another point of focus, Sowell spends much of his time discussing the differences in accountability between institutions. As he puts it, traditional schools have “accountability for following procedures” but not “accountability for end results” (p.68). The reason that teachers cannot be held accountable for results becomes obvious when one looks at what it takes to get rid of a public school teacher. As one investigation reports: “firing an incompetent teacher on average takes 830 days and costs [USD] $313,000” (p.73). The agonizing process that must be endured to get rid of a poorly performing teacher has given rise to two outcomes: the “rubber rooming” of teachers and the “dancing of the lemons”. The former refers to bad teachers who are paid their full salary to turn up and sit in a room, away from any teaching duties, and the latter refers to the method of simply passing bad teachers on to other schools.

Sowell observes another factor which is further decreasing accountability. This is the push to remove the use of test scores when assessing a teacher’s competence. This push is embodied by Professor Diane Ravitch – a historian of education – who insists that “the district or state may aggregate scores for entire schools but should not judge teachers or schools on the basis of these scores” (p.75). It appears that Professor Ravitch is making this well-intentioned case based on the assumption that a focus on testing “quashes imagination, creativity, and divergent thinking” (p.76). But as Sowell distressingly retorts, such downsides are not comparable to the “bitter and lasting consequences” in store for those who fail to gain the fundamental skills needed for a better life (p.77).

Despite these lengthy arguments, Sowell does not pretend to claim that charter schools are a panacea for all students in America. He acknowledges (though perhaps not frequently enough) that some private and public schools can and do outperform charter schools, particularly in well-off neighbourhoods. But he does assert, rather passionately, that charter schools are currently the best at providing economically disadvantaged students with the skills they need to be successful. Skills that well-off children, whether or not they attend a good school, can often attain at home from other family members.

For anyone unfamiliar with the history of charter schools, this book provides great insight into their long-standing struggle to compete for funding within the US, despite their academic success. And with the ongoing pushback against charter schools within New Zealand, we should pause to ask ourselves whether similar results could not be attained here from their expansion. To close, I will leave you with Sowell’s reflection on what is at risk if we fail to defend charter schools:

“The stakes are huge – not only for children whose education can be their one clear chance for a better life, but also for a whole society that needs productive members, fulfilling themselves while contributing their talents to the progress of the community at large. Students who emerge from their education with a mastery of mathematics, the English language and other fundamentals are ready to be those kinds of people, regardless of what colour or class they come from. No narrow vested interests of adults – whether financial, political, or ideological – should be allowed to block that.”

(p.132)

If you enjoyed this BFD article please share it.