Table of Contents

Francis Forde

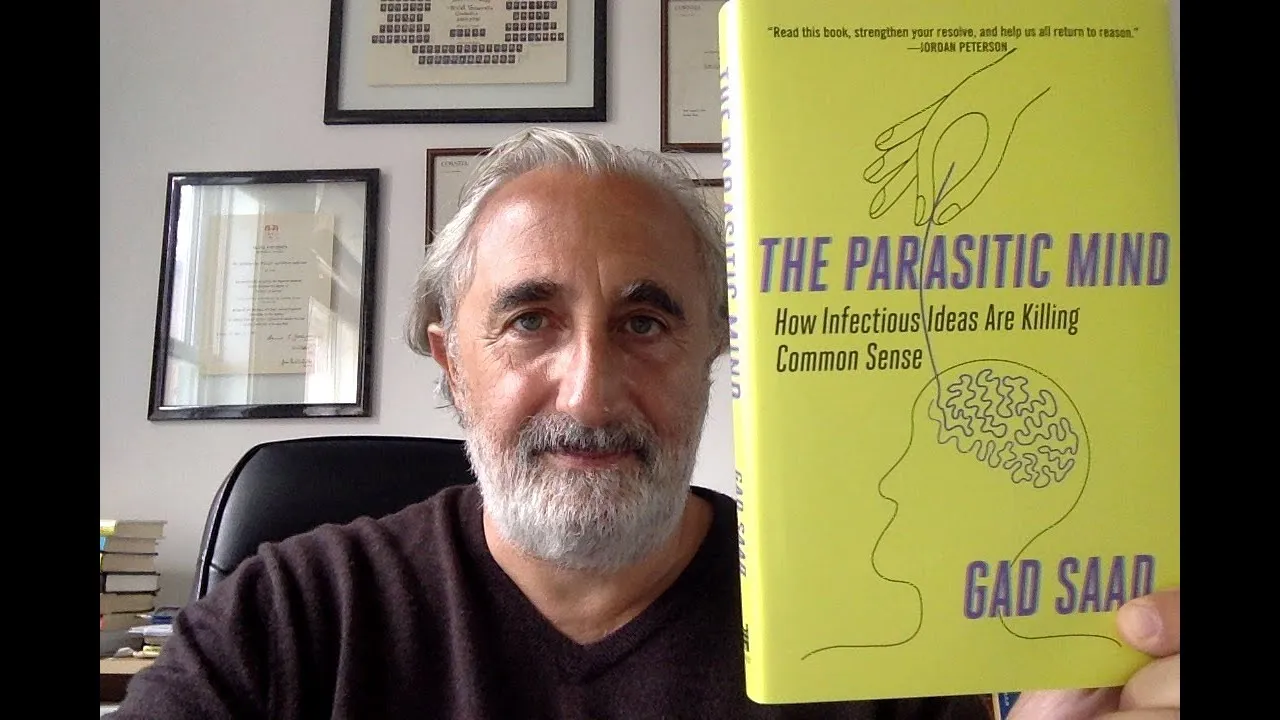

The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense. Hardcover – October 6, 2020 by Gad Saad

In his efforts to stand up to the infantile coddling which is taking place within western institutions, the big bold and beautiful Gad Saad has pulled no punches. In his latest work The Parasitic Mind, Saad dissects the many anti-science and anti-reason scripts that have parasitised the minds of far too many students, professors and social media activists.

With his impeccable victimology credentials – being a Jew who fled ethnic persecution in Lebanon – Saad has managed to surpass many white liberals who radiate anger on behalf of oppressed peoples and has begun to broadcast his voice of reason from the top of the victimology totem pole. While others dare not voice their opinions due to belonging to the dreaded caste of white heteronormative males, Saad is able to circumnavigate this barrier and put some sense back into the world. And while the media may be able to tell a Jordan Peterson to shut up and make room for others, given his status as an old white male, as a brown-skinned man whose mother tongue is Arabic, Gad Saad is a harder foe to squash.

As a professor skilled in the trades of consumer behaviour and evolutionary psychology, Saad was sure to encounter some fierce battles within the halls of academia. In a world where many people deny that the forces of evolution shaped the human mind, despite acknowledging that it influenced everything below the neck, one would be hard-pressed to make it as an evolutionary psychologist without raising some hackles. Thus, Professor Saad is well accustomed to wrestling with those who deny the full implications of Darwinian selection and instead support alternative progressive ideas. But even this background could not spare him the feeling of astonishment as the number of recognised gender identities has exceeded seventy, and when mainstream outlets demonstrate imbecilic ignorance regarding riots, terrorism, and Islamophobia. Even a professor such as Saad, accustomed to encountering intellectual friction and highfalutin’ nonsense, has been forced to double take. And ultimately, it was this sense of bafflement that led him to write The Parasitic Mind.

Flipping through this book, the reader gets a sense of Saad’s charm, wit, and unapologetic hubris. But above all, we gain a fistful of terms and concepts that will prove tremendously useful as we try to rein in the expanding bubble of wokeness. Ostrich Parasitic Syndrome, Collective Munchausen by Proxy, Victimology Poker, the Sneaker Fucker Strategy, and other ideas, allow us to capture certain modes of action and thought which strike many of us as ridiculous but which have previously been hard to pin down. Without the appropriate repertoire of language to classify and label these types of ideas and behaviours that are becoming more common, it can be hard to formulate and direct the relevant critiques. But with these useful descriptions at hand, we are now better placed to call out this utter nonsense and expose it to the light of reason.

Saad’s application of evolutionary theorising also provides a lens through which we can come to understand why these ideas and behaviours are growing in popularity. For example, he provides potential evolutionary reasons for why certain men will exploit any opportunity to be publicly seen as an ally in the movement for gender equity (yes, your intuition here is probably correct). But of course, the reader must be on guard here to avoid being persuaded by fanciful fictions and just-so-stories regarding the origins of human nature. Despite my appreciation of Saad’s work, I think he may too readily provide unrealistic functional accounts of why we behave in certain ways. But having noted this, the scrupulous reader will be able to incorporate these ideas with a grain of salt and use them to develop a new perspective from which political actions and motivations can be seen and considered.

Finally, one of the more important ideas that Saad focuses on later in the book is the construction of nomological networks of cumulative evidence. With its roots in epistemology – the field devoted to understanding how we come to attain knowledge – this strategy for seeking truth is a powerful tool that allows us to converge on good explanations for the phenomena we observe. It can be contrasted with the current strategy that many of us employ, whereby we find a single article supporting our idea and readily espouse that “this is what the science says”. And yes, we all know we do it.

Sadly, this method will not be adequate if we aim to progress the common pot of knowledge and to improve our relationship with people of all political stripes. So instead, to avoid misleading both ourselves and others, nomological networks of cumulative evidence are used to reduce the chances of following falsehoods or statistical flukes. Instead of clutching onto any evidence which leans in our favour, we should look for converging evidence from different disciplines. That is, we should aim to triangulate in on objective reality – just as you do when you incorporate touch, sight, and sound to identify objects in the world.

This means that we should draw from different fields of research and different political sources in order to develop our beliefs and opinions. If we fail to do this, we all risk becoming ideologically parasitised schmucks (as Saad would fondly put it).

If, like myself, you experience a sense of disgust from seeing the kinds of things that pass for credible journalism or correct opinion online today, then you will likely benefit from reading Saad’s book. But if I have not piqued your interest enough, you can do yourself a favour by following Saad on twitter (@GadSaad), as his irony, sarcasm, and wit are something not to miss.

If you enjoyed this BFD book review please share it.