Table of Contents

Kerrie Davies, UNSW

Willa McDonald, Macquarie University

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

In 1886, a year before American journalist Nellie Bly feigned insanity to enter an asylum in New York and became a household name, Catherine Hay Thomson arrived at the entrance of Kew Asylum in Melbourne on “a hot grey morning with a lowering sky”.

Hay Thomson’s two-part article, The Female Side of Kew Asylum for The Argus newspaper revealed the conditions women endured in Melbourne’s public institutions.

Her articles were controversial, engaging, empathetic, and most likely the first known by an Australian female undercover journalist.

A ‘female vagabond’

Hay Thomson was accused of being a spy by Kew Asylum’s supervising doctor. The Bulletin called her “the female vagabond”, a reference to Melbourne’s famed undercover reporter of a decade earlier, Julian Thomas. But she was not after notoriety.

Unlike Bly and her ambitious contemporaries who turned to “stunt journalism” to escape the boredom of the women’s pages – one of the few avenues open to women newspaper writers – Hay Thomson was initially a teacher and ran schools with her mother in Melbourne and Ballarat.

In 1876, she became one of the first female students to sit for the matriculation exam at Melbourne University, though women weren’t allowed to study at the university until 1880.

Going undercover

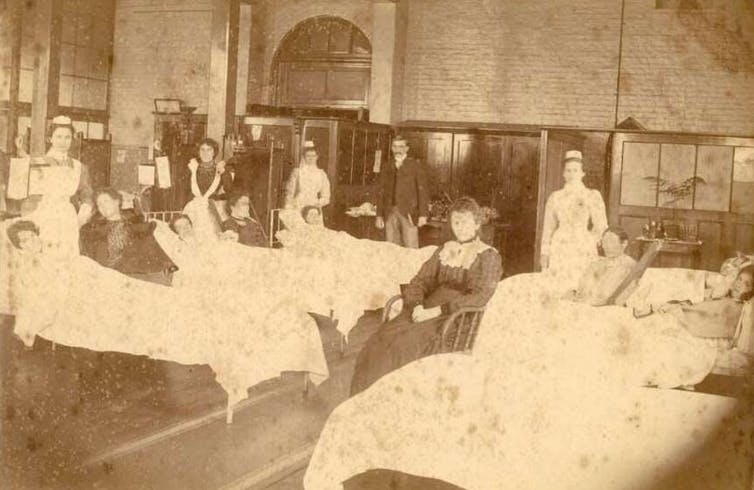

Hay Thomson’s series for The Argus began in March 1886 with a piece entitled The Inner Life of the Melbourne Hospital. She secured work as an assistant nurse at Melbourne Hospital (now The Royal Melbourne Hospital) which was under scrutiny for high running costs and an abnormally high patient death rate.

Her articles increased the pressure. She observed that the assistant nurses were untrained, worked largely as cleaners for poor pay in unsanitary conditions, slept in overcrowded dormitories and survived on the same food as the patients, which she described in stomach-turning detail.

The hospital linen was dirty, she reported, dinner tins and jugs were washed in the patients’ bathroom where poultices were also made, doctors did not wash their hands between patients.

Writing about a young woman caring for her dying friend, a 21-year-old impoverished single mother, Hay Thomson observed them “clinging together through all fortunes” and added that “no man can say that friendship between women is an impossibility”.

The Argus editorial called for the setting up of a “ladies’ committee” to oversee the cooking and cleaning. Formal nursing training was introduced in Victoria three years later.

Kew Asylum

Hay Thomson’s next series, about women’s treatment in the Kew Asylum, was published in March and April 1886.

Her articles predate Ten Days in a Madhouse written by Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Cochran) for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

While working in the asylum for a fortnight, Hay Thomson witnessed overcrowding, understaffing, a lack of training, and a need for woman physicians. Most of all, the reporter saw that many in the asylum suffered from institutionalisation rather than illness.

She described “the girl with the lovely hair” who endured chronic ear pain and was believed to be delusional. The writer countered “her pain is most probably real”.

Observing another patient, Hay Thomson wrote:

She requires to be guarded – saved from herself; but at the same time, she requires treatment […] I have no hesitation in saying that the kind of treatment she needs is unattainable in Kew Asylum.

The day before the first asylum article was published, Hay Thomson gave evidence to the final sitting of Victoria’s Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate, pre-empting what was to come in The Argus. Among the Commission’s final recommendations was that a new governing board should supervise appointments and training and appoint “lady physicians” for the female wards.

Suffer the little children

In May 1886, An Infant Asylum written “by a Visitor” was published. The institution was a place where mothers – unwed and impoverished – could reside until their babies were weaned and later adopted out.

Hay Thomson reserved her harshest criticism for the absent fathers:

These women […] have to bear the burden unaided, all the weight of shame, remorse, and toil, [while] the other partner in the sin goes scot free.

For another article, Among the Blind: Victorian Asylum and School, she worked as an assistant needlewoman and called for talented music students at the school to be allowed to sit exams.

In A Penitent’s Life in the Magdalen Asylum, Hay Thomson supported nuns’ efforts to help women at the Abbotsford Convent, most of whom were not residents because they were “fallen”, she explained, but for reasons including alcoholism, old age and destitution.

Suffrage and leadership

Hay Thomson helped found the Austral Salon of Women, Literature and the Arts in January 1890 and the National Council of Women of Victoria. Both organisations are still celebrating and campaigning for women.

Throughout, she continued writing, becoming Table Talk magazine’s music and social critic.

In 1899 she became editor of The Sun: An Australian Journal for the Home and Society, which she bought with Evelyn Gough. Hay Thomson also gave a series of lectures titled Women in Politics.

A Melbourne hotel maintains that Hay Thomson’s private residence was secretly on the fourth floor of Collins Street’s Rialto building around this time.

Home and back

After selling The Sun, Hay Thomson returned to her birth city, Glasgow, Scotland, and to a precarious freelance career for English magazines such as Cassell’s.

Despite her own declining fortunes, she brought attention to writer and friend Grace Jennings Carmichael’s three young sons, who had been stranded in a Northampton poorhouse for six years following their mother’s death from pneumonia. After Hay Thomson’s article in The Argus, the Victorian government granted them free passage home.

Hay Thomson eschewed the conformity of marriage but tied the knot back in Melbourne in 1918, aged 72. The wedding at the Women Writer’s Club to Thomas Floyd Legge, culminated “a romance of forty years ago”. Mrs Legge, as she became, died in Cheltenham in 1928, only nine years later.

Kerrie Davies, Lecturer, School of the Arts & Media, UNSW and Willa McDonald, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.