Table of Contents

Dr Sheree Trotter

Israel Institute of New Zealand

I recently wrote an op-ed for the New Zealand Herald on President Biden’s recent visit to Israel. Biden boasted of his long history with Israel, having met every Prime Minister since Golda Meir. High on Israel’s agenda for Biden’s visit was the threat from Iran and its proxies in Lebanon and Gaza. Biden and interim PM Yair Lapid signed the Jerusalem US-Israel Strategic Partnership Joint Declaration, in which the US affirmed its commitment “to preserve and strengthen Israel’s capability to deter its enemies”.While Biden pledged a number of measures to improve Palestinians’ daily lives, he stopped short of offering what Abbas really wanted: recognition of the state of Palestine by “enabling the Palestinian people to obtain their legitimate rights and with ending the Israeli occupation of our land”, stating that the “time was not ripe”.

Biden re-affirmed his commitment to a two-state solution, but urged the Palestinians to work “to improve governance, transparency and accountability”, to “combat corruption and advance rights and freedoms, improve community services” in order to “build a society that can support a successful democratic future and a future Palestinian state.”You can read the full article here (though it is paywalled).

Curiously, Biden also stated, in a speech upon his arrival at Ben Gurion Airport, “You need not be a Jew to be a Zionist.” Given the besmirching of the word Zionism in recent decades, this was a surprising admission by the President. While it would be a mistake to read too much into Biden’s statement, it’s a good opportunity to reflect on what Zionism means.

Zionism is generally understood to be the movement for Jewish self-determination and the right of Jews to a nation-state in their ancestral homeland. This should be considered an unproblematic statement. However, Zionism as a word and concept has been under attack at least since the mid-1960s when the Soviet Union singled out Zionism as a supposed form of racism in order to justify its refusal to condemn anti-Semitism during the negotiation of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. A Soviet/Arab alliance pushed their case at the UN, which culminated in the 1975 UN General Assembly Resolution 3379, which determined that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” While this was later revoked, an NGO network, inspired and supported by Israel’s enemies, continues to attack Zionism in an effort to undermine Israel’s legitimacy.

However, it’s worth remembering New Zealand’s traditional support for Zionism. From the signing of the Balfour Declaration in 1917 to the UN Partition Plan in 1947, New Zealand leaders affirmed the right of the Jewish people to a home in their ancient land.

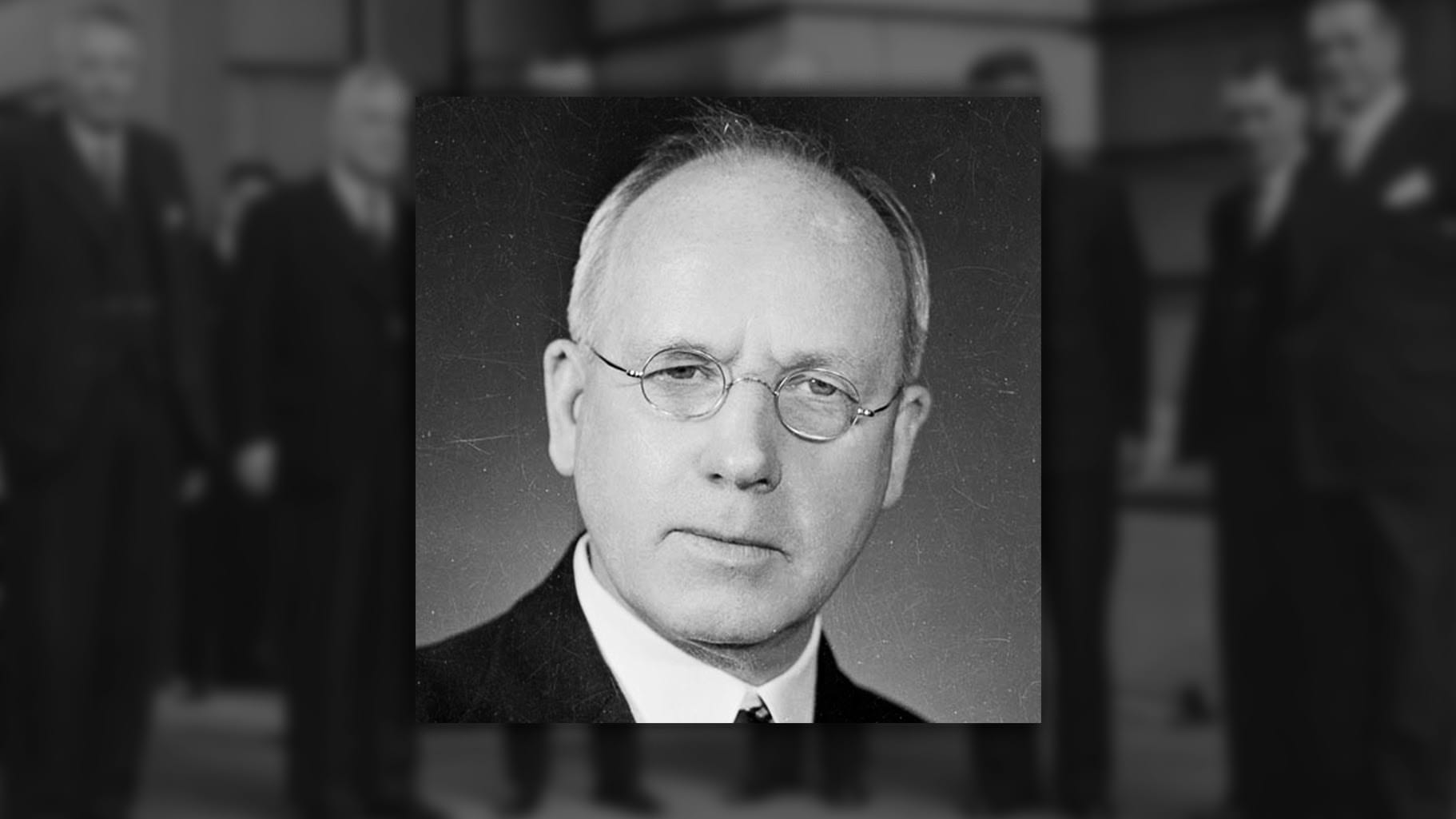

Labour Prime Minister Peter Fraser, who was labelled an ‘exuberant Zionist’, advocated for the Jewish people at the 1945 San Francisco conference, at which the Charter of the United Nations was established. Immediately following WW2 and the discovery of the extent of the Holocaust, and prior to the establishment of the state of Israel, Fraser declared:

“Whatever can be done to help the persecuted Jewish people shall and must be done to the utmost ability of all right-thinking men. There should be no antagonism or misunderstanding between the Jewish and Arab peoples, as everyone living in Palestine would naturally benefit from what the Jewish people have made out of a land which was once desert, until the desert bloomed as a rose. Palestine is very akin to the ideals of New Zealand except that the Jewish people went into Palestine with a tradition of privation… …I hope and believe that the representatives from this country who take part in the council will stand four-square for justice for the ancient home and new hope of the Jewish people.”

Two years later the UN Partition Plan of 1947 was proposed. Fraser saw it as a fair solution that ‘involved the least injustice to the rights of both parties’. He stated that if the Palestinian Arabs were to set up a government within the territory allocated to the Arab State by the General Assembly, NZ would be equally willing to recognise it. However, under no circumstances, would he recognise or accept the right of the Arabs to proclaim a unitary Arab state throughout the whole of Palestine, as such an action would be in flagrant contravention of the General Assembly resolution.

Unfortunately, seventy-five years on, there has been a hardening of positions all round. One can only imagine what might have been if the Arab leadership had then, or on numerous other subsequent occasions, embraced the opportunities offered.