Table of Contents

Roslyn Petelin

The University of Queensland

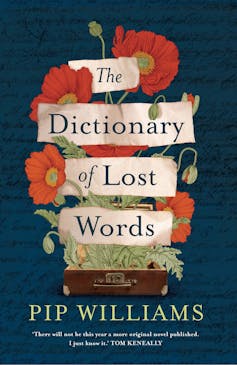

When a literary luminary such as Thomas Kenneally declares so early in 2020 that he is certain a “more original” novel “will not be published this year”, the reviewer faces a challenge. The book in question is The Dictionary of Lost Words, the debut novel by South Australian writer Pip Williams.

Occasionally, I finish a book that I want to immediately read again, such as Alan Bennett’s delectably quirky book, The Uncommon Reader, which I have re-read several times.

I have now read Williams’s book twice. I raced through it the first time to see how it would turn out and needed to read it a second time to pick up what I had missed the first time round. In its 383 pages it covers a timespan of more than 100 years: 1882–1989.

Truth in fiction

The novel is set mainly in Oxford, but events occur in Bath, Shropshire, and Adelaide, Australia.

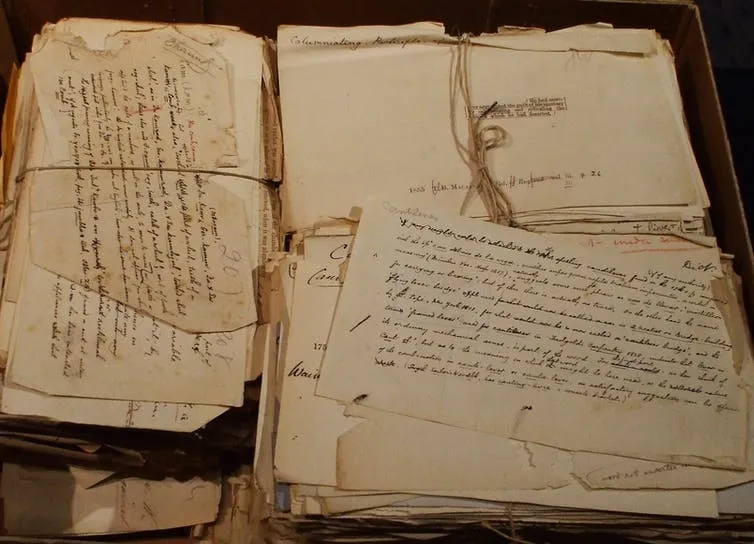

It is based on true events, the central one being the compilation of Oxford University Press’s New English Dictionary (now the Oxford English Dictionary) by a team of lexicographers led by Sir James Murray, and helped by all of his 11 children.

Murray began compiling the dictionary in 1879. It was unfinished at his death in 1915 and completed by his fellow editors in 1928. The second edition appeared in 1989; it is currently being completely revised.

Other historical figures who play key roles in the novel are printer Horace Hart and lexicographer Henry Bradley, who succeeded Murray.

Author Pip Williams speaks about her novel.

Women’s words

Williams’s fictional central character, Esme Nicoll, born in 1882, lives with her father Harry, a lexicographer who works on the dictionary in a corrugated iron shed, grandly called the Scriptorium. It sits in the garden of Murray’s house, Sunnyside, at 78 Banbury Road in Oxford. Esme has lost her mother at a very young age.

She spends her days beneath the sorting table in the “scrippy”, where the lexicographers sort and assess the potential contributions sent to Murray by volunteers following his worldwide appeal for words to be included in the new dictionary.

One day, a lexicographer drops off a slip of paper. It falls under the table and Esme rescues it. She places it inside a small wooden suitcase kept under the bed of the Murrays’ housemaid Lizzie. The word is “bondmaid”, which is exactly what Lizzie is. Lizzie supplies her own entry: “Bonded for life by love, devotion or obligation. I’ve been a bondmaid to you since you were small, Essymay, and I’ve been glad for every day of it”. The word is not discovered to be missing until 1901.

Over several years, Esme secretes a trunkful of words:

My case is like the Dictionary, I thought. Except it’s full of words that no one wants or understands, words that would be lost if I hadn’t found them.

Esme and Lizzie also collect words from stallholders in Oxford’s Covered Market, many of them “vulgar”.

Esme‘s gathered words comprise the book published many years later, titled in the novel as Women’s Words and Their Meanings, after Lizzie passes Esme’s collection on to a compositor at the Press. However, when Esme subsequently presents a copy of the volume to an editor who takes over after Murray’s death, he rejects it as unscholarly and not a “topic of importance”, confirming Esme’s experience that “all words are not equal”.

She responds to him: “you are not the arbiter of knowledge, sir. It is not for you to judge the importance of these words, simply allow others to do so”.

Williams grafts an emotional story onto other historical figures and interweaves the themes of women’s equality and the suffrage movement. The suffragist-suffragette divide is layered into the narrative when Esme’s actor friend, Tilda, heeds Emmeline Pankhurst’s “deeds, not words” call to action and ends up committing arson.

A minor character is Esme’s godmother Edith, whose earnest epistles to Esme and her Dad move the plot along, including a painful episode when Esme is treated harshly at a Scottish boarding school. Esme undergoes many changes in fortune, finding some happiness as the story unfolds.

Judge the book

Reviewing this book, I’m reminded of a quote in Putnam’s Monthly magazine of American literature, science and art from April 1855:

I proclaim to all the inhabitants of the land that they cannot trust to what our periodicals say of a new book. Instead of being able by reading the criticism to judge the book, it is now necessary to read the book in order to judge the criticism.

My advice to readers is similar: experience The Dictionary of Lost Words for yourselves rather than getting swept away by the hype. Don’t gobble it, as I did the first time round – savour its heart-wrenching detail.

Unfortunately, a close read does reveal the need for a tighter copy edit. “Radcliffe” is spelt two different ways on opposite pages; “braille” is misspelt; the main street in Oxford is known as “the High” rather than “High Street”. I circled (in pencil) dozens of instances of my pet peeve “different to”.

Regardless, it has had an astonishing pickup by international publishers, who clearly expect it to be a commercial success. It will certainly be a popular book-club choice. Time will tell whether it takes its place beside literary classics.

The Conversation has been contacted by Affirm Press who assure us one of the typing errors mentioned did not go to final printing of the book and appeared only in the advance copies. Another error mentioned will be fixed in subsequent printings.

Roslyn Petelin, Course coordinator, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD.