Table of Contents

Tiger

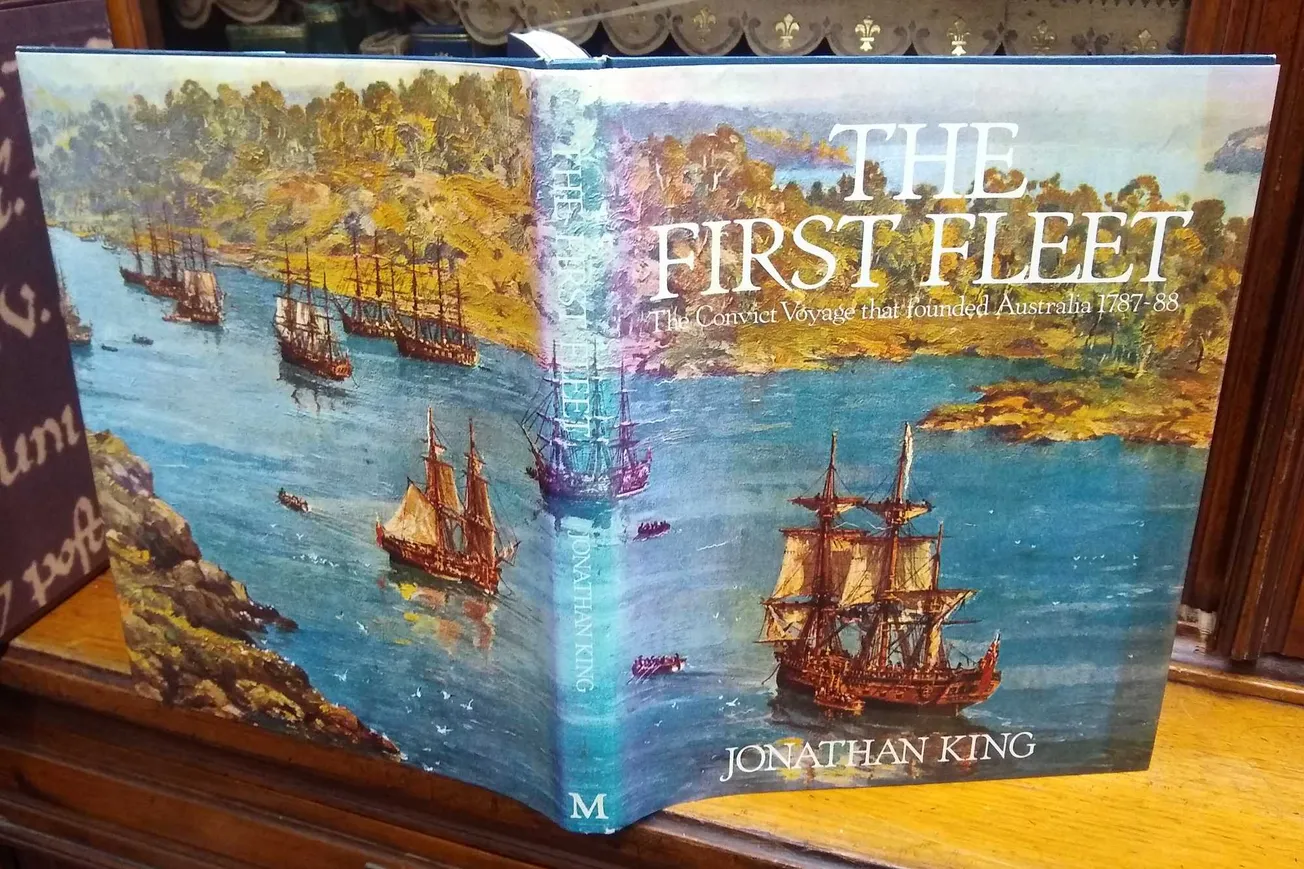

The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage that founded Australia 1787-1788

Author: Jonathan King

ISBN 0-333-33855-3

I picked up a copy of this book at a local second-hand bookstore. It turns out it was signed by the author on the bicentenary of the fleet’s arrival at Port Jackson after a disappointing attempt to settle at Botany Bay.

As a history buff I was keen to know more about the settlement of Europeans in our region. I had no more expectation than a blow-by-blow historical record. It turns out this book was quite the page-turner.

The book contains a sequence of daily events, from the moment the ships were being provisioned in London, then Portsmouth, to the day they decided that Port Jackson, not Botany Bay, was the place to set up the new colony.

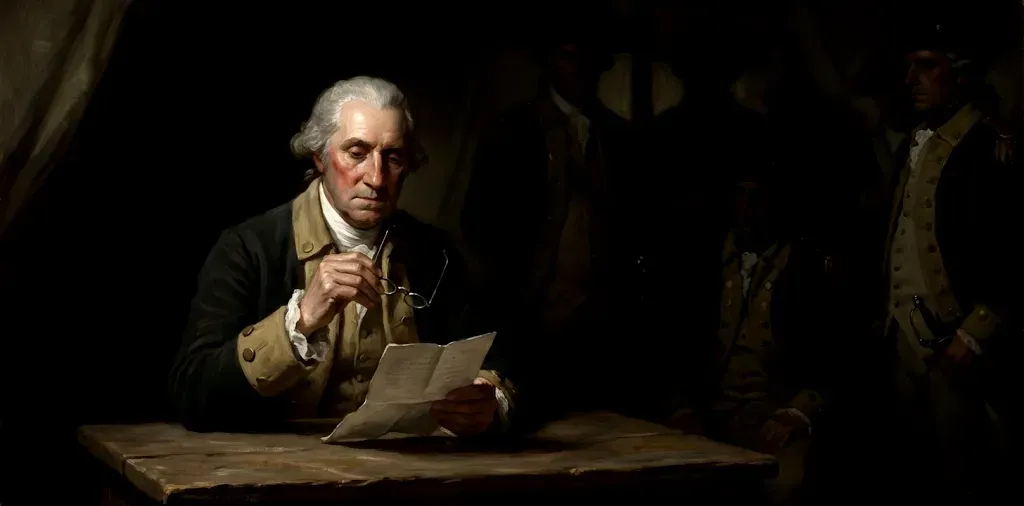

What this book offers is a first-hand account, from the writings of several passengers aboard the eleven ships that finally left an inner anchorage off Portsmouth on 13 May 1787. The trials of the convicts, some merely there for stealing food, began with the near four month wait on board through the English winter as Commodore Arthur Phillip (Commander in Chief of the fleet) battled bureaucracy and bad publicity to ready the fleet.

After journeying to Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, Cape of Good Hope, then finally Botany Bay, around New Holland (Tasmania), a remarkably few died (48) out of a total of 1,350 who set out.

Whilst the book gives a good account of the epic maritime journey itself, it is the detail of goings on amongst the convicts, crew, officers and marines that makes this book interesting. First-hand accounts in “flexible” English, of debauchery, theft, shenanigans, mutinies, court martials, punishment by lashing, births, deaths, the state of livestock and plants, lend a gritty reality to the harsh journey. In an age without navigation lights, GPS, radar, sonar and such, this book impresses upon the reader how treacherous the journey was.

On the matter of some missing islands on charts of the Canaries, Watkin Tench, captain of the Charlotte and the marines writes, “It is no less extraordinary than unpardonable, that in some very modern charts of the Atlantic, published in London, the Salvages are totally omitted.”

Fresh water and food were a constant worry. The health of the travellers was a matter of concern for the fleet doctor, Chief Surgeon John White. Finding a balanced diet as supplies dwindled was an ever-present challenge. The convicts were important as they had to be alive and fit when arriving in Australia. Drunkenness was a major problem, such as when Sergeant John Kennedy as described by James Scott, “being disguised in liquour and abusing several people in the ship, jumped down the main hach way upon my wife as she sat at work just by the lader. And like wise hurted her greatly (sic).”

Having females on board most of the ships was a novelty for many of the marines and crew, not only the wives of officers, but the many female convicts who by their very nature as thieves and prostitutes were prone to use their wily ways to gain favours and generally cause mayhem.

A group of women of particular repute were dubbed the “fighting five” and were responsible for causing a lot of trouble throughout the journey, ironically on a ship named the Friendship. When not clapped in irons, they were stealing or prostituting themselves to anyone willing and who had access to their quarters. The guards (marines) were not exempt from partaking in debauchery, and when caught suffered punishment of up to 150 lashes.

Convicts, being convicts, were also prone to fraud; in one instance they fashioned counterfeit coins in their quarters to trade at various ports. It is remarkable they were able to access materials and tools to do so with such limited resources. The plot was uncovered just before Rio de Janeiro, where a counterfeit incident might have upset the peaceful reception the English fleet got from the Portuguese Governor.

When the fleet got into Botany Bay, from the moment they anchored, the crew, “hurriedly cut grass for the remaining livestock, caught fish for the humans, made peace with the natives and tried to find running water and good soil for their land base.”

Most of the native encounters the colonists had were peaceful. Some incidents were defused either through gifts of beads or cloth, a novelty for the totally naked peoples. The natives were confused about the sex of the colonists, who covered up their nethers in clothing. This led to some awkward exchanges where the crew had to drop their breeches to demonstrate they were men. The native men did not want to interact with women. They were however encouraging of the newcomers to partake of their women’s “charms”, something the officers banned.

Not a few days later a French exploration fleet arrived in Botany Bay, signalling a race of the European rivals to establish colonies in the Southern hemisphere.

A second fleet of only three transports had been dispatched from England in 1790, with much less success, with 267 deaths along the way.

Whilst the author, a historian of renown, captures the day to day trials of the fleet, he also paints a picture of resilience and fortitude I doubt many today could sustain. One can only admire the leadership of this very successful fleet as they took an ark of limited means to a strange world to set up what is today a very successful country.

What the book does give us (tongue in cheek) is an inkling of the progenical nature and difference to us our sunburnt cousins in Australia have today. After all, the Judge Advocate of the fleet, David Collins, mused,

“If only it were possible, that on taking possession of Nature, as we had thus done, in her simplest, purest garb, we might not sully that purity by the introduction of vice, profaneness, and immorality. But this though much to be wished, was little to be expected.” Of course not, not with a fleet of convicts.