Table of Contents

John Maunder

When I was in Canada about 30 years ago, I listened to a lecture about Medieval Warming, the building of the Gothic Cathedrals and the freemasons. It appears that there was no theological reason why the cathedrals were built at that time but there is an interesting link between the warmth of Europe in the 11th to 15th centuries, the wine of England, and the freemasons and their lodges.

The Medieval Warm Period is an epoch of relatively warm climate which existed in the 10th-13th centuries, following the climatic pessimum of the Great Migration and preceding the so-called Little Ice Age of the 14th-18th centuries. Prior to current theories about human-induced global warming – a full 400–700 years before humans began the Industrial revolution – the Medieval warm period’s mild winters and relatively warm and even weather allowed for unprecedented crop growth, urban expansion, and the establishment of Scandinavian settlements in Greenland and North America.

Rather than limiting the Medieval warm period to “Europe and neighbouring regions or the North Atlantic”, Willie Soon and Sallie Baliunas of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics found 112 studies containing information about the medieval warm period in Russia, the U.S. Corn Belt, Central Plains and Southwest; much of China and Japan; southern Africa; Argentina, Chile and Peru, America, Australia and Antarctica … in the Indian Ocean, both central and southern; and in the Central and Western Pacific Ocean. In the Southern Hemisphere, twenty-one of twenty-two studies showed evidence of Medieval Warming.

Climate became distinctly more benign

Thomas Gale Moore of the Hoover Institution wrote about the Medieval Warm Period:

“The three centuries beginning with the eleventh century, during which the climate became distinctly more benign, witnessed a profound revolution which, by the late 1200’s had transformed the landscape into an economy filled with merchants, vibrant towns and great fairs. Crop failures became less frequent; new territories were brought under control. With a more clement climate and a more reliable food supply, the population mushroomed.”

The historian Charles Van Doren claimed that:

“the … three centuries, from about 1000 to about 1300, became one of the most optimistic, prosperous, and progressive periods in European history.”

All across Europe, the population went on an unparalleled building spree, erecting at huge cost spectacular cathedrals and public edifices. Ponderous Romanesque churches gave way to soaring Gothic cathedrals. Virtually all the magnificent religious shrines that we visit in awe today were started by the optimistic populations of the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries, although many remained unfinished for centuries.

Many of the Gothic cathedrals of Europe were built or were commenced during the period 1100-1400. This period was a time of warming (in some cases warmer than at present) when abundant crops were available to provide food for the builders of the cathedrals. There appears to be no theological reason why the cathedrals were built at that time, but the development of architectural techniques was a significant factor. Perhaps the main reason why the cathedrals were built was related in whole or in part to the warmer weather.

Masons in Medieval England

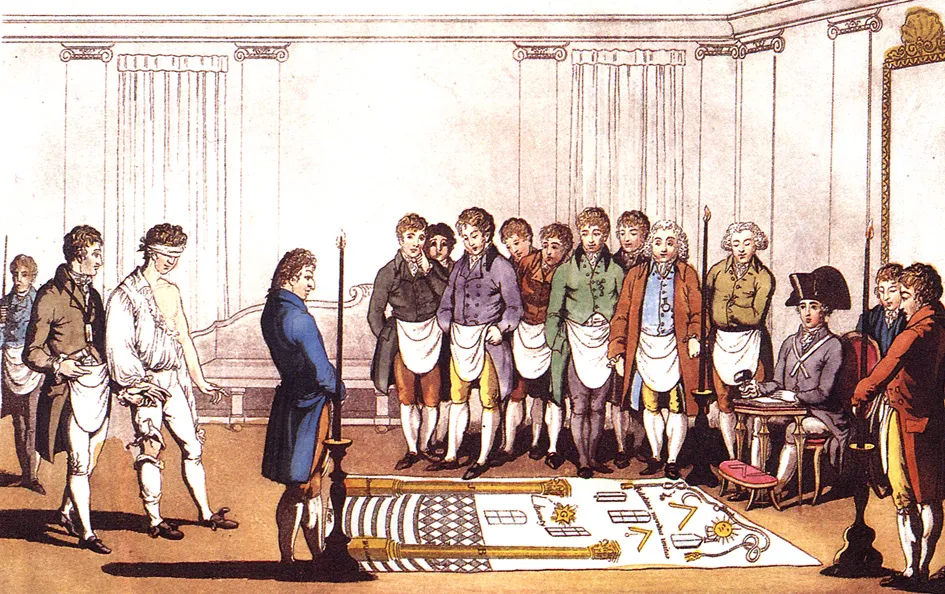

Masons in Medieval England were responsible for constructing some of England’s most famous buildings. Masons were highly skilled craftsmen and their trade was most frequently used in the building of castles, churches and cathedrals. Masons belonged to a guild. However, a mason’s guild was not linked to just one town as the members of the mason’s guild had to move to where building was required. The Mason’s Guild was an international one and even in Medieval England, the guild was sometimes referred to as the “Free Masons”. ‘Free’ stone was the name of the stone commonly used by masons as it was soft and facilitated intricate carvings.

Masons tended to lead nomadic lives. They went where there was employment. Other tradesmen could effectively stay where they were as there was enough trade for their skill to allow them to settle. However, masons had to move on to their next source of employment once a building had been completed – and that could be many miles away.

A mason would have an apprentice working for him. When the mason moved on to a new job, the apprentice would move with him. When a mason felt that his apprentice had learned enough about the trade, he would be examined at a Mason’s Lodge. If he passed this examination of his skill, he would be admitted to that lodge as a master mason and given a mason’s mark that would be unique to him. Once given this mark, the new master mason would put it on any work that he did so that it could be identified as his work.

A mason at the top of his trade was a master mason. A Master Mason, by title, was the man who had overall charge of a building site and master masons would work under this person. A Master Mason also had charge over carpenters, glaziers etc. In fact, everybody who worked on a building site was under the supervision of the Master Mason. He would work in what was known as the Mason’s Lodge. All important building sites would have such a building that served as a workshop and a drawing office from which all the work on the building site was organised. Anyone who arrived at the building site and claimed that they were a master mason would be tested by the Master Mason and by master masons already working on the site. By doing this they ensured that quality was maintained – and that they would have a good chance of future building work.

Trademark carvings

When a Master Mason moved on, he took his lodge with him. That does not mean the physical building but the organisation and culture of the Master Mason and those who worked with him. Even the carving of sub-parapet friezes – a very localised phenomenon – suggests a building culture at work amongst the masons, and very certainly amongst one or more Master Masons. Beyond that, however, and most telling of all, is the plethora of “trademark carvings”- notably the mooning man – that are surely products of what we would today call a corporate identity. That identity was surely forged in the closed world of the Lodge.

The word “freemason” does not appear, according to Knoop and Jones, until 1376. That it does so quite late in the medieval period might have something to do with the advance of English at the expense of Latin (and French) in the world of commerce. In its origin, the word “freemason” would undoubtedly seem connected with “freestone”, which is the name given to any fine-grained sandstone or limestone that can be freely worked in any direction and sawn with a toothed saw.

So we can see that the freemason was not defined by his “freedom” as many assume (all masons were equally free or otherwise) but by his ability to work in the finest stone that was used for the most decorative purposes. Nor was he defined by membership of some mystical “order” of mason’s hierarchies, secrets and rituals such as characterise the modern (or, as they would prefer to see it, ancient) institution of Freemasonry. Knoop and Jones uncovered evidence that one of the first tasks of the Master was to prepare templates made of wood or sheet metal. If he needed a cross-section of a pillar, for example, he would make a template for his men to copy. Similarly for window tracery. Some of these templates still exist in the roof of York Minster. There were writings and drawings available but they were scarce and expensive. Also the plans for a church would call for an impracticable large canvas. The masons, then, would draw in a box filled with sand or plaster. Again, at York Minster the “drawing floor” still exists.

There can be no doubt that masons in Medieval England were highly skilled craftsmen. Testimony to their work stands today in the numerous cathedrals and castles that still exist.

Economic activity in Europe

Throughout Europe economic activity blossomed during this period of warming. Banking, insurance, and finance developed; a money economy became well entrenched; manufacturing of textiles expanded to levels never seen before. Farmers in medieval England launched a thriving wine industry. Good wines demand warm springs free of frosts, substantial summer warmth and sunshine without too much rain, and sunny days in the autumn. The northern limit for grapes during the Middle Ages was about 500 km north of the current commercial wine areas in France and Germany.

The medieval warm period, which started a century earlier in Asia, benefited the rest of the globe as well. From the ninth through the thirteenth centuries, farming spread into northern portions of Russia. In the Far East, Chinese and Japanese farmers migrated north into Manchuria, the Amur Valley and northern Japan. The Vikings founded colonies in Iceland and Greenland, then actually green. Scandinavian seafarers discovered “Vinland” along the East Coast of North America.

The systematic investigation of a possible medieval climate anomaly – especially in Europe – was initially the field of historical climatology. Long before the beginning of instrumental measurements, a record of climate change could be drawn from historical documents and archaeological finds, leading to conclusions on climatic conditions and their consequences. Thus, for the period from about 1300, there are reasonably complete historical reports of summer and winter weather. It was through the pioneering work in this field, of the British climatologist Hubert Lamb and the French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, that the first comprehensive overviews of higher temperatures and social contexts for the North Atlantic and Europe were delivered.

Medieval Warm Period

The term “medieval warm period” was then primarily influenced by the work of Hubert Lamb of the University of East Anglia in the 1960s, and later adopted by other fields of research. Lamb called this a global warming, which he stated regionally with an increase up to 1-2°C and whose peak he suspected was between the years 1000 and 1300. Lamb found evidence of such warming, especially around the North Atlantic, while there were indications of relatively low temperatures for the North Pacific at about the same time. As a cause, he assumed displacements of the Arctic polar vortex.

BUY Your Own Copy of Dr John Maunders book Fifteen Shades of Climate Today.