Table of Contents

Regina Scheyvens

Apisalome Movono

Massey University

Regina Scheyvens is Professor of Development Studies at Massey University, where she combines a passion for teaching about international development with research on tourism and sustainable development.

Dr. Apisalome Movono has an undergraduate background in Marine Management and Tourism Studies and completed his Master of Arts Degree from The University of the South Pacific.

With the reopening of New Zealand’s borders from next week, the future of tourism comes into sharp relief. Flattened by the pandemic and having survived on domestic consumption for two years, the industry has a choice: try to revive the old ways, or develop a new model.

If tourism minister Stuart Nash has his way, there is no going back. “Tourism won’t return to the way it was,” he told Otago University’s Tourism Policy School recently, “it will be better.”

But how? The question is coming down to the various definitions of “value” – both the monetary and less tangible kinds.

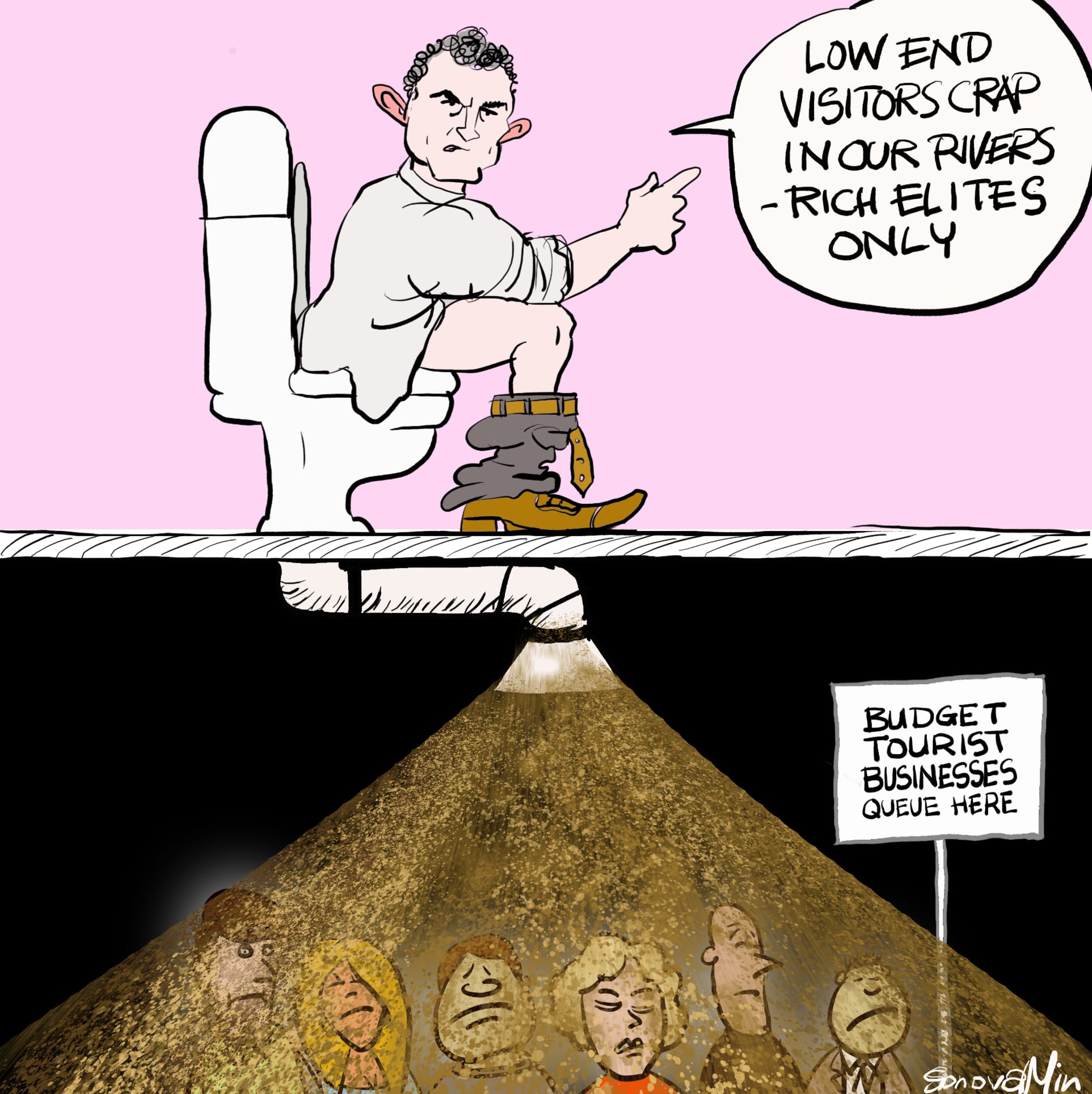

When Nash addressed a tourism summit in late 2020, “high value” clearly meant “high spending”. New Zealand would “unashamedly” target the wealthy – the type of tourist who “flies business class or premium economy, hires a helicopter, does a tour around Franz Josef and then eats at a high-end restaurant.”

The minister also asked: “Do you think that we want to become a destination for those freedom campers and backpackers who don’t spend much and leave the high net worth individuals to other countries?”

There was immediate concern that such a policy would overlook the broader value of “lower-end” tourism: backpackers and other budget tourists might not spend as much per day, but they tend to travel for longer periods, bring dollars to remoter locations, and often work in understaffed industries like horticulture and hospitality.

At the same time, high-spending tourists hiring helicopters tend to place a high per-capita burden on the environment and contribute more to climate change. Clearly, what constitutes “high value” is up for debate.

From high value to high values

Now, however, the minister is defining the high-value tourist differently. They give back more than they take, appreciate those working in the tourism sector, are keen to learn about the people and places they are visiting, are environmentally aware and offset their carbon emissions.

This shift in thinking prompted one participant at the tourism policy school to suggest that instead of “high value” tourism, New Zealand needs to be talking about “high values” tourism.

The sentiment chimed with the policy school’s theme of “structural change for regenerative tourism”, and a general feeling that this will involve looking inward to certain core values that matter to the country.

Attendees – including industry leaders, academics, government officials and tourism business owners – supported the idea that “regenerative” in this context matches the important Maori values of kaitiakitanga, kotahitanga and manaakitanga, which should inform the future direction of tourism in Aotearoa.

Mana and manaakitanga

The implications of this approach were well articulated by Nadine ToeToe, director of Kohutapu Lodge, an award-winning tourism business in the central North Island. She proposed a new tourism model that advances manaakitanga (kindness and hospitality) to guests, while also enhancing the mana of their hosts, local communities and the surrounding environment.

With her business based in the area around Murupara, which is beset by historical injustices and downturns in the forestry industry, ToeToe described the potential of tourism to move beyond simple service industry conventions.

Rather, more authentic, culturally embedded experiences could be offered, based on building respectful relationships with the people and places visited. This would mean manaakitanga was reciprocal, benefiting both guests and local communities.

By being designed to enhance people, community and place, tourism would necessarily break from the old volume-driven model that was putting many natural environments under significant pressure prior to the pandemic.

Time for a reset

Of course, it is one thing to suggest that tourism respect the wairua (spirit) of the land, and quite another to put the legislative and regulatory frameworks around a pathway to sustainability.

To a degree this is beginning to happen already. For example, following concerns about a promised crackdown on freedom camping, the minister stepped back from banning vans that weren’t self-contained. However, proposed policy changes will go to select committee this year, with new rules to be rolled out gradually from next summer.

These should align with the minister’s view that “… at the heart of the new law will be greater respect for the environment and communities through a ‘right vehicle, right place’ approach” (with fines of up to NZ$1,000 for offenders).

The challenge now is to broaden that vision beyond individual businesses, or pockets of concern such as freedom camping, to encompass the entire industry. Because there can be no better time than now for a values-based reset of New Zealand tourism.

Regina Scheyvens, Professor of Development Studies, Massey University and Apisalome Movono, Senior Lecturer in Development Studies, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.