Table of Contents

Kerri Duncan

Kerri is an Adelaide-based freelance writer with a background in animal science and molecular biology. Always up for an investigative adventure, Kerri is addicted to exploring Earth’s wonders and finding as many waterfalls as possible. Her work in life sciences has deepened her appreciation of the natural world and she feels compelled to write about it.

Flesh-eating bacteria may sound like something out of a sci-fi movie, but that’s what many are calling the bugs responsible for the Buruli ulcer.

Hundreds of people in Victoria have been affected by the skin disease.

Cases have risen by 50% every year since 2015, and it’s expanding into new areas.

Exactly how Buruli ulcer spreads has been a mystery for a long time. As a result, scientists aren’t sure on how to stop it either. But a world-first research project, Beating Buruli ulcer in Victoria, is working on answers.

The team, including scientists from the Telethon Kids Institute, have developed a new tool for surveilling and predicting outbreaks of the ulcer.

And the tool’s key ingredient is possum poo.

‘TERRIBLE, FLESH-EATING ULCERS’

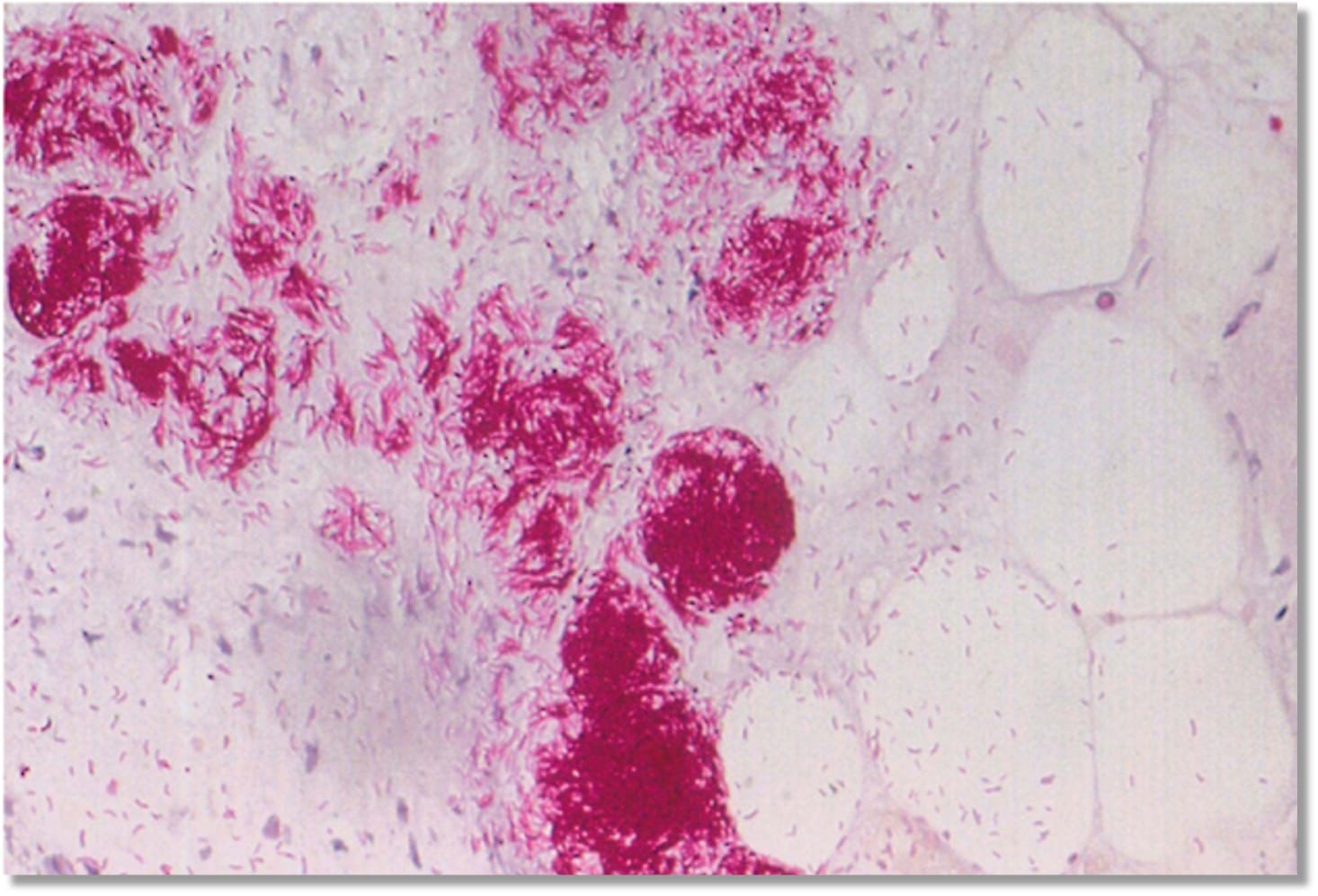

The Buruli ulcer is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans. It comes from the same group of bacteria that cause tuberculosis and leprosy.

The bacterium produces a toxin that damages the skin.

Dr Andrew Buultjens is a research officer at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne. He says an unusual aspect of the disease is its lengthy incubation period.

Symptoms often don’t appear until 4–5 months after exposure.

“It gets under the skin and grows slowly to cause terrible flesh-eating ulcers,” says Andrew.

NOT SO EXOTIC

Another intriguing factor is where the ulcers are occurring in Australia.

The World Health Organization recognises Buruli as a “neglected tropical disease”.

But the majority of Australian cases have been reported in southeastern Victoria.

“There’s a significant burden of the disease in regions such as Melbourne and Geelong,” says Andrew.

“[These] have temperate, rather than tropical climates.”

“THE GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF BURULI ULCER REMAINS A FASCINATING PUZZLE.”

A PERFECT STORM?

Humans pick up Buruli ulcer infections from the environment. Human-to-human transmissions are extremely rare.

Animals like possums harbour the bacteria in their gut and pass it on to mosquitoes, which infect humans.

Four elements enable human transmission. First, the introduction of the bacteria into the environment and wildlife reservoirs (like native possums) to house and grow the bacteria. Then, a high density of mosquitoes to spread the bacteria and a population of humans exposed to mozzie bites.

Andrew suggests these elements may be converging at the “right time and place” in areas they weren’t previously.

“Given enough time and opportunity, the risk areas for Buruli ulcer could continue to grow,” he says.

WHAT’S POO GOT TO DO WITH IT?

Possums, the suspected primary wildlife reservoirs, shed bacteria in their poo.

M. ulcerans can be detected in poo samples taken from areas where Buruli ulcers are common.

“Our research involves systematically collecting possum poo in the suburbs of Melbourne,” says Andrew.

“Although it may not be the most glamorous job, it plays a vital role in our investigation.”

The scientists record precise GPS locations of the sample sites. A sophisticated mathematical model developed by the team then produces high-resolution risk maps.

These maps act as an early warning system for populations that are at risk of contracting Buruli ulcer.

THEY’VE GOT YOUR BAC-TERIA

Andrew says identifying where ulcer cases may show up can help authorities “get ahead of the curve”.

“With early warning insights, the health department can … notify communities in high-risk areas,” he says.

“[They] could be advised to take preventive measures.”

Locals can reduce their risk of infection by avoiding mosquito bites and reducing mosquito breeding opportunities.

Doctors can also receive a heads-up to expect cases in the area.

“[This is] likely to translate to early diagnosis, leading to timely treatment and better patient outcomes,” says Andrew.

FUTURE POSSUM VAX?

The research highlights the crucial role possums play in transmitting the disease to humans.

Because of this, Andrew says there is interest in exploring vaccines for possums.

“Similar efforts have been undertaken in controlling tuberculosis in domestic livestock through possum vaccination campaigns in New Zealand,” he says.

“Stopping the disease in possums would be an effective intervention to stop both possums and humans getting Buruli ulcer.”