Table of Contents

Feng Wang

Professor of Sociology

University of California, Irvine

Throughout much of recorded human history, China has boasted the largest population in the world – and until recently, by some margin.

So news that the Chinese population is now in decline, and will sometime later this year be surpassed by that of India, is big news even if long predicted.

As a scholar of Chinese demographics, I know that the figures released by Chinese government on Jan. 17, 2023, showing that for the first time in six decades, deaths in the previous year outnumbered births is no mere blip. While that previous year of shrinkage, 1961 – during the Great Leap Forward economic failure, in which an estimated 30 million people died of starvation – represented a deviation from the trend, 2022 is a pivot. It is the onset of what is likely to be a long-term decline. By the end of the century, the Chinese population is expected to shrink by 45%, according to the United Nations. And that is under the assumption that China maintains its current fertility rate of around 1.3 children per couple, which it may not.

This decline in numbers will spur a trend that already concerns demographers in China: a rapidly aging society. By 2040, around a quarter of the Chinese population is predicted to be over the age of 65.

In short, this is a seismic shift. It will have huge symbolic and substantive impacts on China in three main areas.

Economy

In the space of 40 years, China has largely completed a historic transformation from an agrarian economy to one based on manufacturing and the service industry. This has been accompanied by increases in the standard of living and income levels. But the Chinese government has long recognized that the country can no longer rely on the labour-intensive economic growth model of the past. Technological advances and competition from countries that can provide a cheaper workforce such as Vietnam and India have rendered this old model largely obsolete.

This historical turning point in China’s population trend serves as a further wake-up call to move the country’s model more quickly to a post-manufacturing, post-industrial economy – an aging, shrinking population does not fit the purposes of a labour-intensive economic model.

As to what it means for China’s economy, and that of the world, population decline and an aging society will certainly provide Beijing with short-term and long-term challenges. In short, it means there will be fewer workers able to feed the economy and spur further economic growth on one side of the ledger; on the other, a growing post-work population will need potentially costly support.

It is perhaps no coincidence then that 2022, as well as being a pivotal year for China in terms of demographics, also saw one of the worst economic performances the country has experienced since 1976, according to data released on Jan. 17.

Society

The rising share of elderly people in China’s population is more than an economic issue – it will also reshape Chinese society. Many of these elderly people only have one child, due to the one-child policy in place for three and a half decades before being relaxed in 2016.

The large number of aging parents with only one child to rely on for support will likely impose severe constraints – not least for the elderly parents, who will need financial support. They will also need emotional and social support for longer as a result of extended life expectancy.

It will also impose constraints on those children themselves, who will need to fulfil obligations to their career, provide for their own children and support their elderly parents simultaneously.

Responsibility will fall on the Chinese government to provide adequate health care and pensions. But unlike in Western democracies that have by now had many decades to develop social safety nets, the speed of the demographic and economic change in China has meant that Beijing struggled to keep pace.

As China’s economy underwent rapid growth after 2000, the Chinese government responded by investing tremendously in education and healthcare facilities, as well as extending universal pension coverage. But the demographic shift was so rapid that it meant that political reforms to improve the safety net were always playing catch-up. Even with the vast expansion in coverage, the country’s healthcare system is still highly inefficient, unequally distributed and inadequate given the growing need.

Similarly, social pension systems are highly segmented and unequally distributed.

Politics

How the Chinese government responds to the challenges presented by this dramatic demographic shift will be key. Failure to live up to the expectations of the public in its response could result in a crisis for the Chinese Communist Party, whose legitimacy is tied closely to economic growth. Any economic decline could have severe consequences for the Chinese Communist Party. It will also be judged on how well the state is able to fix its social support system.

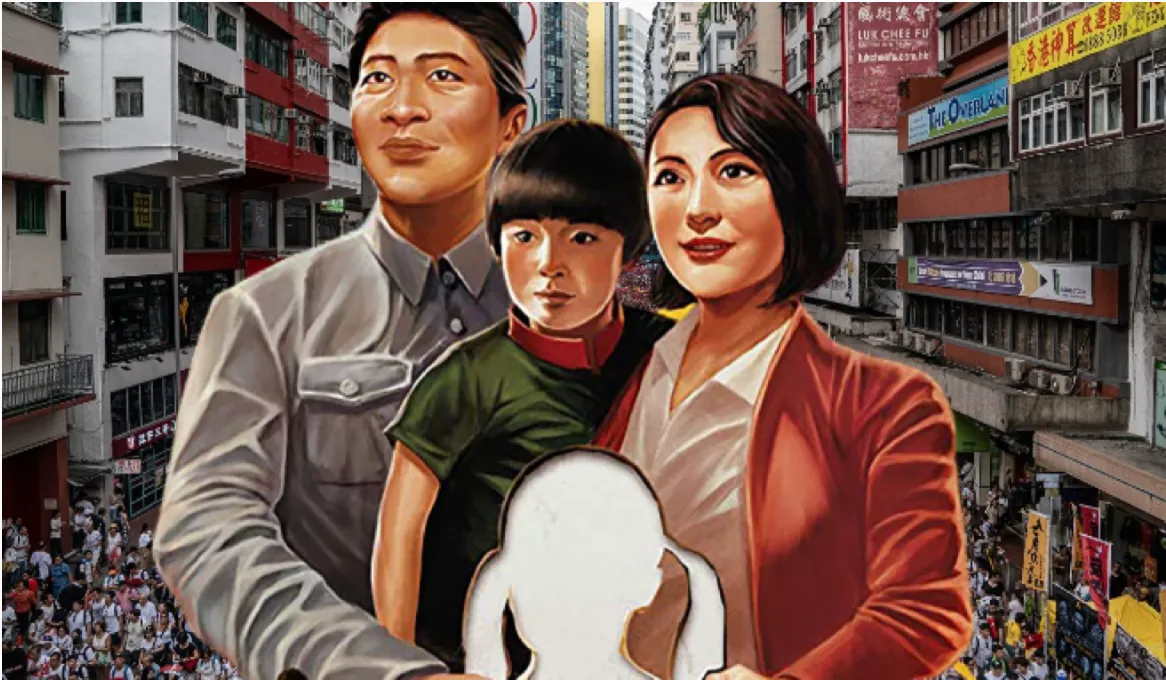

Indeed, there is already a strong case to be made that the Chinese government has moved too slowly. The one-child policy that played a significant role in the slowing growth, and now decline, in population, was a government policy for more than three decades. It has been known since the 1990s that the Chinese fertility rate was too low to sustain current population numbers. Yet it was only in 2016 that Beijing acted and relaxed the policy to allow more couples to have a second, and then in 2021 a third, child.

This action to spur population growth, or at least slow its decline, came too late to prevent China from soon losing its crown as the world’s largest nation. Loss of prestige is one thing though, the political impact of any economic downturn resulting from a shrinking population is quite another.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.