Table of Contents

You can read the first part of my review of the 2020 Church & State Summit in Auckland here. The conference is aimed at equipping and encouraging Christians and churches to be more involved in culture and politics.

The final speech prior to the dinner break was professor Paul Moon from AUT. He talked about the problem of hate speech, why it’s not able to be defined in law, and what we should do about it.

He started off by giving a good overview of what constitutes hate speech and how it develops. I’ve never heard any anti-hate speech legislation proponent ever give a good definition of hate speech, but a member of the Free Speech Coalition did their legwork for them. According to Paul Moon, hate speech is that which contributes nothing to discourse. Hate speech comes from a place of animosity within the speaker, who intends to inflict pain with his words. Unlike things spoken in anger, the animosity behind hate speech does not dissipate over time. The internet facilitates “hate speech spirals” due to the constraints of the medium that encourage a cycle of ad hominem attacks.

While it’s possible to generate rules around what is genuinely hate speech, it’s not possible to have everyone agree on whether a specific statement is hate speech. After all, you can’t read the mind and heart of the speaker to determine if they are hateful. Professor Moon provided a number of examples to the room, and there was no consensus on a single line whether it met the criteria he had laid out. Most of the lines he used as examples were spoken by local clerics or ambassadors belonging to a certain obscure religion.

He then moved into the area of attempting to legislate anti-hate speech laws. The United Nations’ proposals hinge on the perception of disharmony and eerily would only apply to protect the religions and feelings of ethnic minorities. If hate speech is that dangerous, why not protect everyone from it?

Paul Moon gave a specific example. If you select a random religion starting with “M”, say Methodists, and walked into their church and expressed some distasteful views of John Wesley, you’d probably be at grave risk of being served a cup of lukewarm tea. That benign interaction might not hold steady for all religions whose practitioners start with “M”.

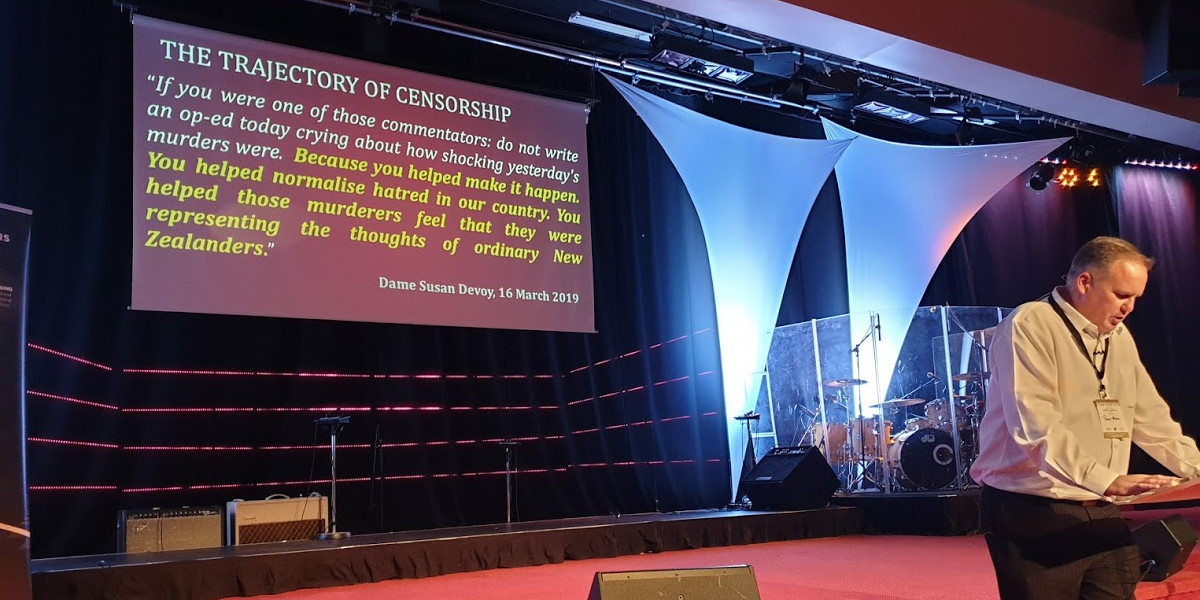

That’s the real danger of hate speech laws based on the perception of disharmony. Those who receive the speech can determine your punishment via their reactions. Any laws based on people’s feelings would inevitably end in a brutal exercise of mob rule and repression. One does not have to look further than the following quote by Dame Susan Devoy to see where this will lead:

What does all this have to do with the Bible and Christianity?

Professor Moon used the medieval Catholic Church as an example of how historic “hate speech” laws have affected Christianity. “The Catholic Church wasn’t well known for its tolerance and freedom of speech,” he started with, quickly adding “of course, they’re a lot different today.” A great adaption of the ancient anti-bigotry defence followed in jest: “Some of my best friends know some Catholics.”

He gave examples of Reformers and how their arguments around access to the Bible in the vernacular were “hate speech” to many in the Church (and State). Take the following quote from Wycliffe: “Believers should have the Scriptures in a familiar language. Moses heard God’s law in his own tongue.” Hate speech? How about this famous quote from Tyndale: “I will cause a boy who drives a plough to know more of the Scriptures than the Pope”? Definitely hate speech.

He highlighted how ancient pagan societies were reformed by those early Christians who were viewed as madmen and heretics to the dominant culture. This was a good flow-on from one of Dr. Michael Brown’s points: “a lot of what the world calls extremist and fanatical, God calls normal.”

Moon went through a few more examples, such as a number of Puritans and early classical liberals who fought for religious toleration and freedom of speech. If hate speech had been illegal, would those agitating for the abolition of slavery have succeeded? It was a nephew of William Wilberforce who pushed for Governor Hobson to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, ending slavery in these islands and founding the nation we live in today. In more modern times, Christians like Kate Shepherd and Martin Luther King likewise used the power of speech to achieve their aims. I later realised that many of the works of the early church fathers we have are apologetic works—ideas they wrote down to argue against false teachers and haters. There’s so much literature that would not have flourished or been available with widespread anti-hate speech laws.

Professor Paul Moon ended his presentation by linking free speech to responsibility. We should use speech as an aim to establish the truth and not an end in itself. The antidote to hate speech is responsible speech. Suppression does not get rid of hatred. Force sacrifices intelligence. Hate speech can be unpalatable, but the alternative is worse.

During Q&A, Paul Moon took a question from someone asking if churches should perhaps be apathetic to freedom of speech as Christianity is growing under oppression in China and dying in the West. The professor had a brilliant counterpoint, using the example of the Soviet Union which nearly wiped out the church. Since the fall of communism and the rise of free speech, Christianity has rebounded and flourished in Eastern Europe. He warned the audience to be wary of seeing correlations and to instead focus on the Bible’s command to promote justice and peace in government.

Come back in a few days for part 3 of this review that will focus on Dave Pellowe’s exhortations for the church to “build the wall” and Dr Michael Brown confronting the “spirit of Jezebel” — both sessions that deserve some extended commentary such as Prof Paul Moon’s did.

https://thebfd.co.nz/2020/03/part-one-church-state-summit-a-roaring-success/

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.