Table of Contents

Tell me it isn’t true! Surely the models are not programmed to show a warming world as a result of increasing CO2?

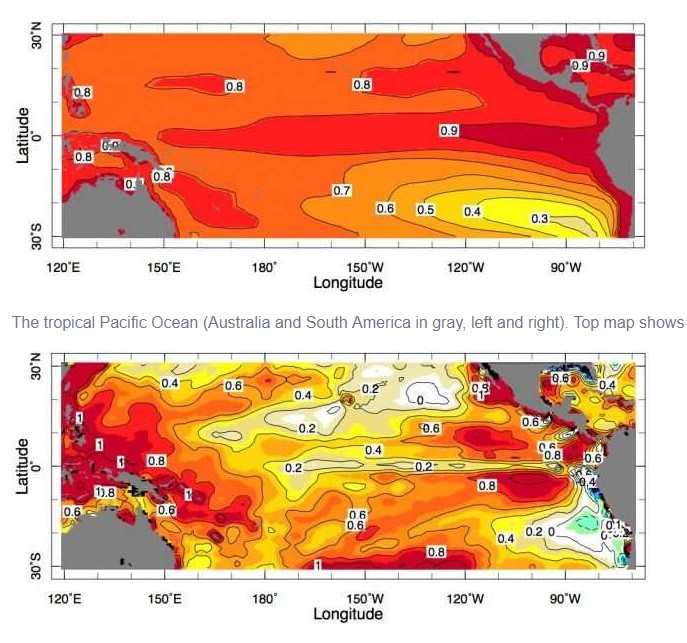

State-of-the-art climate models predict that as a result of human-induced climate change, the surface of the Pacific Ocean should be warming—some parts more, some less, but all warming nonetheless. Indeed, most regions are acting as expected, with one key exception: what scientists call the equatorial cold tongue. This is a strip of relatively cool water stretching along the equator from Peru into the western Pacific, across quarter of the earth’s circumference. It is produced by equatorial trade winds that blow from east to west, piling up warm surface water in the west Pacific, and also pushing surface water away from the equator itself. This makes way for colder waters to well up from the depths, creating the cold tongue.

Climate models of global warming—computerized simulations of what various parts of the earth are expected to do in reaction to rising greenhouse gases—say that the equatorial cold tongue, along with other regions, should have started warming decades ago, and should still be warming now. But the cold tongue has remained stubbornly cold.

This troubles many scientists, because the cold tongue plays a key role in global climate. For example, it affects the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, a natural cyclic strengthening and weakening of the trade winds that causes cooling and warming of the eastern Pacific surface every two to seven years. ENSO is the world’s master weather maker; depending on which part of the cycle it is in, its echoes in the atmosphere may bring heavy rains or drought across much of the Americas, east Asia and east Africa. Whether the cold tongue warms will likely affect weather across huge regions. Resulting shifts could affect world food supplies and outbreaks of dangerous weather. But our predictions of those shifts rest on climate models.

Richard Seager, a climate scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, has long suspected that climate models get the cold tongue wrong. In 1997, he and colleagues published a paper suggesting that it had not warmed at all during the 20th century. At the time, most scientists assumed that any discrepancy between real-world temperatures and those predicted by climate models were due to natural variability. We should just wait; eventually the signal of cold tongue warming would emerge. Now, two decades later, with more modern satellite data in hand, real-world observations are veering ever more obviously from the models. It is time to reconsider, says Seager. […]

The mismatch between observed changes in cold tongue temperature over past decades and the models is quite striking. There are scores of simulations with multiple models from research groups across the world. While these models are all forced by the same histories of greenhouse gases, volcanoes, solar radiation and other forces, they generate their own internal variability. Hence they create a range of estimates of climate history. For changes in cold-tongue temperature, the observed changes are at the far cold end or outside the model range. The average or median model says the cold tongue should have warmed by 0.8 degrees C or more over the past six decades, but the real value is only 0.4 degrees or less.

Well, they’ve been out of line for decades. This is not a new problem. […] The implication for modelers is that they must find out why their models have biases, and fix them.

Phys.org