Table of Contents

Michael Bassett

Political historian Michael Bassett CNZM is the author of 15 books, was a regular columnist for the Fairfax newspapers and a former minister in the 1984–1990 governments.

Ever wondered who or what is constantly trying to block the new government’s policies? Why is it that announcements by ministers about the economy, educational changes, new health proposals, reducing the runaway numbers of public servants and combating juvenile crime, are quickly met with so-called leaked bits of advice about how the new ideas have been ‘tried before and don’t work’? Leading to cocky assertions from the Labour Opposition that the media then highlight. Frequently, the minister is the last person allowed media space.

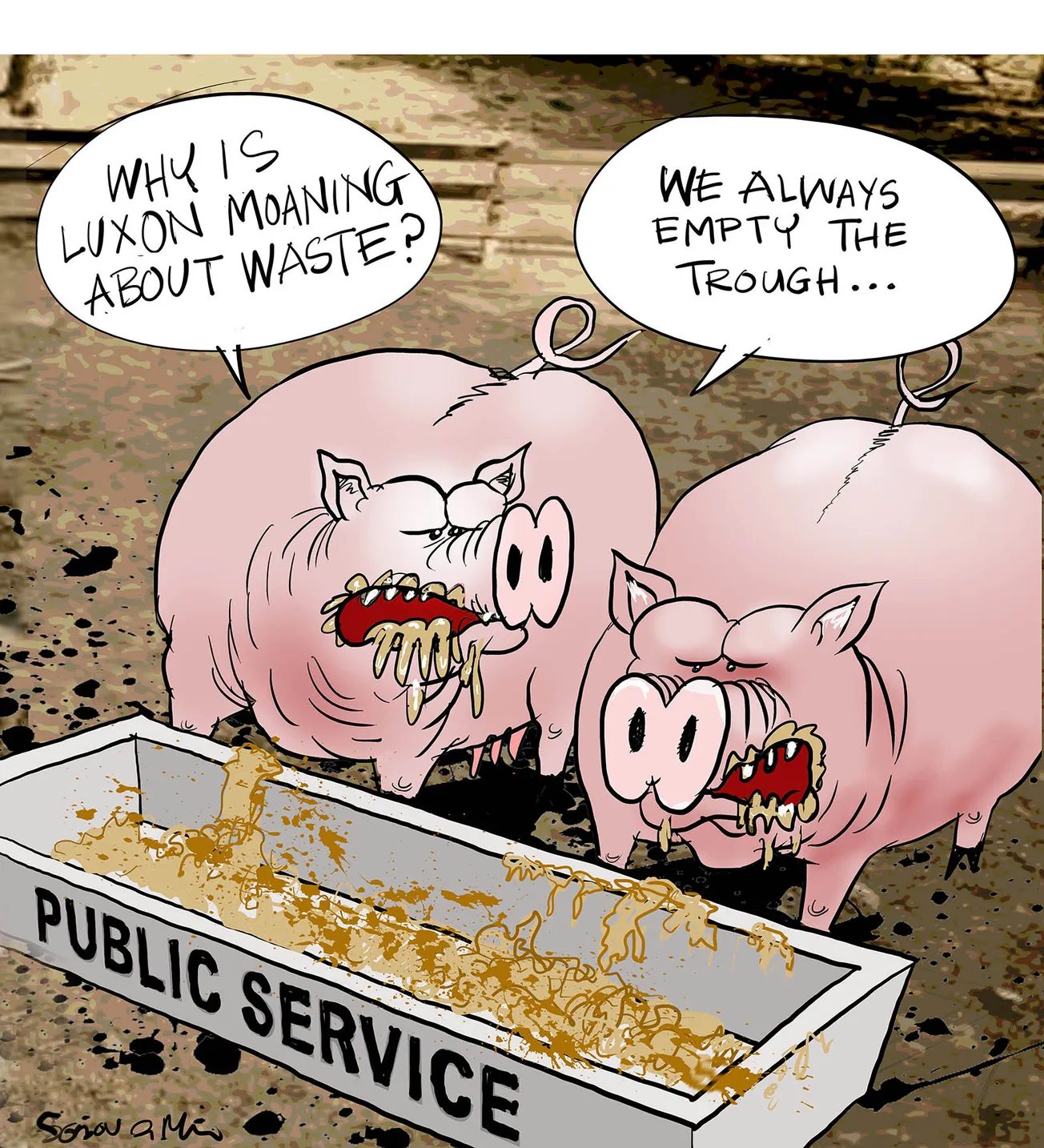

Remembering the ways in which the same sorts of people tried to block progress when I was a minister during the major reforms of the 1980s, I detect a similar pattern emerging amongst those opposed to change. Many influential people seem born to resist it. Their positions depend on the status quo. Several bad eggs around the Public Dis-Service Association are constantly receiving information from unhappy civil servants, and in turn the P(D)SA provides it to selected journalists who then produce columns that used to be called “stinky fish articles”. They attack the new policies before the wider public have been able to get their heads around what the Cabinet is actually proposing. The difference between now and the 1980s is that Chris Luxon’s government doesn’t know how to handle such blockades and too often shuffles about like Joe Biden on a bad day.

Stinky fish material appeals to many journalists at the New Zealand Herald and to the likes of TV One’s Te Aniwa Hurihanganui, Maiki Sherman, Jacob Johnson, and to Radio NZ, which often just chronicles criticisms of ministerial intentions. Such journalism sends reassuring messages to the lack-lustre lot that believed in Jacinda, Chippy, the Greens and those even nearer the lunatic fringe of politics. The media quibble about what ministers are proposing, blowing them up to headlines criticising policy. “Don’t ban smartphones for school kids”; “Don’t remove urban limits for housing”. Journalists get away with not finding any alternative policies to report, and often don’t even acknowledge there are serious problems in need of fixing. They just let the criticisms do their wicked work.

The current strategic political problem stems from the fact that National Party politicians don’t instinctively think of reform. They are more used to administering the status quo. Right now, they are faced with a slew of problems because a recklessly spending Labour government was convinced that anything could be solved if money was borrowed and thrown at it. So far, National has slowed the wasteful spending juggernaut, but restructuring is another matter. Its two partners in government are less traumatised by the thought of reform, particularly ACT, which was founded on an understanding that significant structural social and economic change is vital if New Zealand is to keep abreast of the world. But convincing National is clearly an uphill task

If the Coalition wants to be re-elected in 2026 it needs a more cohesive approach to pushing ahead with change. David Lange’s government that took office 40 years ago this month faced problems of a similar magnitude to those facing the Luxon-led ministry today. Trade unions, the P(D)SA and elements within the Labour Party tried to stop the remedial actions that were taken by Lange’s new cabinet. Roger Douglas, who was Minister of Finance, had been around politics long enough to understand his opponents and decided early in the piece to speed up the reform process. Before long, so many new policies were appearing that opponents didn’t know how to prioritise their attacks. Speed is a key to achieving reform. Occasionally the Lange government suffered from speed wobbles, but as ministers held their nerve and explained what they were doing, and why, new ways of doing things were consolidated. The public bought devaluation and floating of the dollar, the introduction of GST, and the turning of loss-making government trading departments into State Owned Enterprises. A clear overall plan kept the show on the road. Rapid momentum and clear explanations were vital. The government’s share of the vote increased at the following election.

Public divisions between ministers, and hesitations over policy implementation, tell the voting public that something is amiss. Blurting out general intentions without specifics as to policy is also careless. This last week’s announcement that law and order would be a ministerial goal for the next 100 days invited immediate questions about specific policies which Luxon then dived for cover rather than answer. Better to say nothing than start shooting half-cocked.

More is needed. The Lange government reformed key parts of the State Services as well. Luxon and Nicola Willis have insisted on some reductions to the bloated bureaucracy they inherited. Civil Servants need to realise that if they continue to play games leaking material and being truculent over policy implementation then further staff retrenchments will occur, and the salaries saved will be put into buying services from consultants. A few fires lit in your critics’ backyards can also be powerful aids to progress. But the process requires determined, consistent leadership, which these days is rather too intermittent to leave me feeling confident that enough reform will be achieved to stop New Zealand’s downward slide.

This article was originally published by Bassett, Brash & Hide.