Table of Contents

It was a year ago that Ian “Ollie” Olsen passed away after a long battle with the incredibly rare and cruel disease Multiple System Atrophy, so it seems a good time to honour his life and work as the quintessential influential outsider. Never a household name, Olsen occupies a peculiar place in Australian music history: an artist whose influence far outstripped his chart success. Revered by his peers and collaborators, who included some of the most famous names in popular music, Olsen may have seldom been feted by the pop charts, but he created a vast body of work and a lasting legacy over some 50 years.

“Ollie” as he was better known, was born Ian Christopher Olsen in 1958, in the Melbourne suburb of Blackburn, originally part of Melbourne’s semi-rural fringe that was home to the famous ‘Heidelberg School’ of impressionist painters, including Tom Roberts and Fred McCubbin.

In his teens in mid-’70s, Olsen developed an interest in electronic music and studied under Felix Werder, the German-born Australian composer of classical and electronic music. Then punk set off a nuclear explosion in popular music and Olsen was caught up in the cultural firestorm. Ultimately it was his early grounding in electronic music fused with punk’s rock riotousness that shaped Olsen’s entire unique career. Early on he began to break away from punk’s template of guitar-based rock’n’roll to explore ground that almost no one else in the world was at the time.

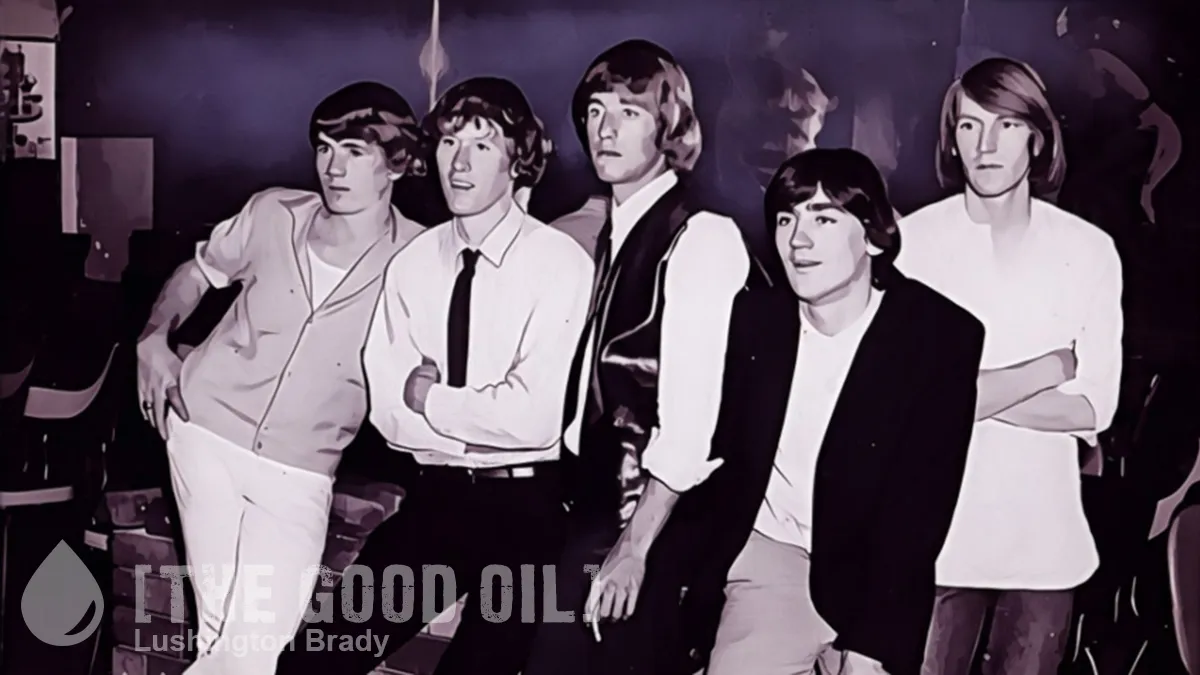

His earliest bands, the Reals and the Young Charlatans, characteristically brought him into the orbit of musicians who would go on to become part of other legendary Australian bands. Rowland S Howard, who wrote the classic “Shivers” aged just 16, joined Nick Cave in the Boys Next Door, later the Birthday Party, following the dissolution of the Young Charlatans. Another Young Charlatans member, Janine Hall, went on to perform with the Saints and Wedding Parties Anything.

Meanwhile, Ollie Olsen threw himself into the ‘Little Bands’ scene based in the inner Melbourne suburb of Richmond. While across the Yarra, in the once-posh seaside haven of St Kilda, the main punk scene was populated by slumming private school kids full of arty pose, Richmond’s Little Bands scene was more authentically grubby and visceral. It drew its name from the whirlwind of little bands who formed and merged in a creative swirl, often performing just one or two gigs, sometimes impromptu, and swapping band members like hippies swapping venereal diseases.

The Little Bands scene showcased Olsen’s two great strengths: bringing a more experimental electronic edge to punk and building collaborations with other creatives. It was the former that made Olsen’s first sustained attempt to take post-punk elsewhere, the band Whirlywirld. Formed just two years after New York’s more celebrated duo, Suicide, Whirlywirld explored remarkably similar territory: confrontational, spare and interested less in verse-chorus hooks than in tone, rhythm and atmosphere. Like Suicide, Whirlywirld employed tapeloops, synthesizers and industrial percussion to create a performance of dark, machine-driven menace that anticipated the rise of industrial electronic music later in the ’80s.

Olsen, however, was nothing if not restless: over the next few years he dabbled in a kaleidoscope of projects, from the weirdly obscure Hugo Klang to the avant-garde electronic chamber-music ensemble Orchestra of Skin and Bone. Across these projects Olsen’s role shifted – sometimes vocalist, sometimes instrumentalist, sometimes architect of soundscapes – but the throughline was constant: a refusal to settle into a commercially legible identity and a taste for collaborative instability.

It was at this time, too, that Olsen experienced his one and only chart success and collision with fame.

Richard Lowenstein’s 1986 film, Dogs in Space, is a roman à clef of the Little Bands scene, filmed in the very Richmond house Lowenstein shared with some of the Little Bands members. The film follows the misadventures of fictional group ‘Dogs in Space’ and their drug-addled singer, ‘Sammy’: both loosely based on singer/writer/actor Sam Sejavka and his band The Ears (Sejavka was understandably disgruntled by the portrayal of him in the film).

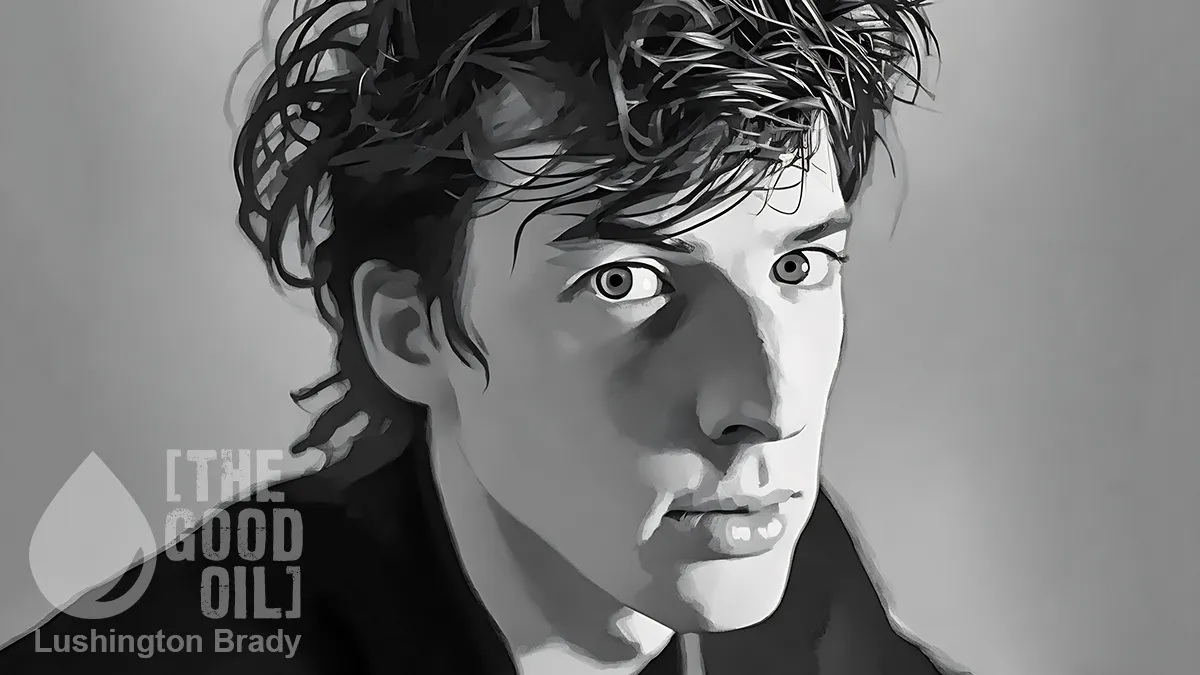

While Olsen was musical director of the film, reforming many of the Little Bands to play and record for film scenes and the movie’s soundtrack, the lead role of Sammy was played by Michael Hutchence. Yes, that Michael Hutchence. Hutchence was by 1986 a bona fide international superstar, thanks to INXS’ massive global success.

Hutchence contributed vocals to several songs on the film, including a re-recording of Whirlywirld’s “Rooms for the Memory”. The unlikely duo hit it off, and briefly formed the Max Q project – a short-lived but culturally resonant collaboration that paired Hutchence’s charismatic voice with Olsen’s underground credentials and production instincts. Max Q released one self-titled album and several singles. Max Q was certified gold, while the single “Way of the World” reached the Top Ten in both Australia and New Zealand.

Max Q was an anomaly in both men’s careers: for Hutchence it was an exploratory departure from INXS’s stadium polish; for Olsen it was a rare tour into a larger pop audience.

Hutchence was one of the most recognisable pop stars of the 1980s, while Olsen was everything the pop machine was not: a divisive, experimentalist presence with few radio hits to his name. The collaboration therefore amplified both their contrasts and their compatibilities. In particular, Olsen’s composition “Rooms for the Memory” – recorded in the late 1980s and associated with Hutchence – is an instance where an outsider’s writing became briefly visible to the mass audience that Hutchence could deliver.

Yet even that visibility was ephemeral: for Olsen the encounter with fame did not translate into a mainstream career. Perhaps by choice... He had demonstrated his capacity to translate his underground sensibility into a form that could, at least for a moment, engage mainstream ears. Yet Max Q’s very existence also confirmed the pattern of Olsen’s career: he could step into the bright light when invited, but he would not – and perhaps could not – be captured by it. The mainstream flirtation was intense and public but ultimately short.

If Whirlywirld had been just a year behind Suicide, Olsen’s project following Max Q, the band No, beat the more famous Nine Inch Nails to the same industrial territory by a similar margin. Across two albums (Glory For the Shit for Brains, and Once We Were Scum, Now We Are God), No’s marriage of heavy rock guitar, drum machines, synthesisers and knife-edged vocal screams anticipated NIN’s debut Pretty Hate Machine by a good two years, with none of the latter’s success, of course.

If the 1980s for Olsen were defined by collaborative experiments that occasionally brushed celebrity, the 1990s and beyond mark his most decisive shift: a deliberate re-alignment with electronic dance cultures, not as a trend follower but as an early adopter and theorist. Olsen co-founded Psy-Harmonics, an independent label that became a key outlet for Australian psychedelic trance and experimental electronic music; he recorded under aliases such as Third Eye and worked on early acid-house and trance permutations in Australia. This transition was not a betrayal of his earlier aesthetic but its logical continuation: where Whirlywirld had pursued mechanical repetition, and Orchestra of Skin and Bone had interrogated texture and timbre, Third Eye and Psy-Harmonics permitted Olsen to explore rhythm as trance, to build immersive sonic environments rather than conventional songs. It is here – behind the decks, in small clubs and in DIY networks – that his influence on younger producers and DJs grew most direct.

In his later years Olsen applied his restless curiosity to film sound design, scoring and teaching. He lectured on electronic music, worked on scores for film and television and continued to produce records and remixes for underground scenes. Even as illness curtailed his output in the late 2010s and early 2020s, his imprint remained evident in the producers and labels who had learned, explicitly or otherwise, from his example.

‘Outsider’ is often deployed as a put-down: in Olsen’s case it is more properly a description of a deliberate aesthetic and ethical orientation. He cultivated a career that made influence – not charts – the primary metric of success. Friends and collaborators repeatedly observed that he preferred the company of fellow misfits and that he was a consummate collaborator who shied from celebrity structures even when they came calling. This stance had costs: financial precarity, a smaller recorded catalogue in conventional terms and a public reputation that never reached the scale of some of his contemporaries. But it also yielded freedoms – to invent, to fail spectacularly and move on, to nurture fledgling artists through labels and mentorship and to insist that music could be a site of risk rather than product. Those freedoms help explain why so many younger artists – DJs, producers, noise-makers and experimentalists – cite him as an inspiration even if they could not point to him as a hit maker.

Assessing Olsen’s legacy is partly a matter of reading influence sideways: not in the immediacy of chart positions but in the slow accretion of ideas, techniques and sensibilities. Ollie Olsen’s is not a story of frustrated ambition so much as of constancy, without betraying an underlying aesthetic: a belief in the power of texture, repetition and collaborative improvisation.

Ian Olsen “died peacefully in his sleep” with his wife Jayne at his side, at Royal Melbourne Hospital, on October 16th, 2024, but his legacy will not be forgotten, at least, not by the happy few of the right people.