Table of Contents

The 1950s rock’n’roll explosion hit Australia just as it did the rest of the world and spawned a flurry of early stars like Col Joye, Digger Revell and, of course Johnny O’Keefe. It was J’OK who also gave the world the enduring hit, “Wild One (Real Wild Child)”, covered by everyone from Jerry Lee Lewis to Iggy Pop, the Runaways and even Josie and the Pussycats.

By the early-mid ’60s, the Australian rock’n’roll scene had flagged, consisting mostly of local bands recording cover versions of overseas hits. Then, from the middle to late ’60s, something extraordinary happened, partly fuelled by Ten Pound Pom kids landing up in Bonnegilla and Villawood immigrant camps with suitcases carrying the latest singles from the British Blues Explosion bands. It was at Villawood that the Scot George Young met Dutch kid Harry Vanda, spawning the Easybeats.

There was another force at work, too, one harder to define but easy to hear. Scrappy, aggressive, working-class energy channeled through distortion, volume and attitude. A raw, defiant sound that would later be recognised as proto-punk. While the Easybeats became a popular sensation and produced the second great song of Australian rock’n’roll, “Friday On My Mind”, a host of other bands like the Missing Links, the Black Diamonds, the La De Da’s, the Wild Cherries, the Purple Hearts, the Throb and the Blues Stars rocked the garages and the grimy dance halls of King’s Cross and Melbourne. Some would come and go in a two-minute blast of fuzz, but others would forge lasting careers through the ’60s and ’70s, and the echoes of their rockin’ noise would feed on into later, much more famous acts, like Radio Birdman, the Saints and AC/DC (featuring even more of the redoubtable Young family).

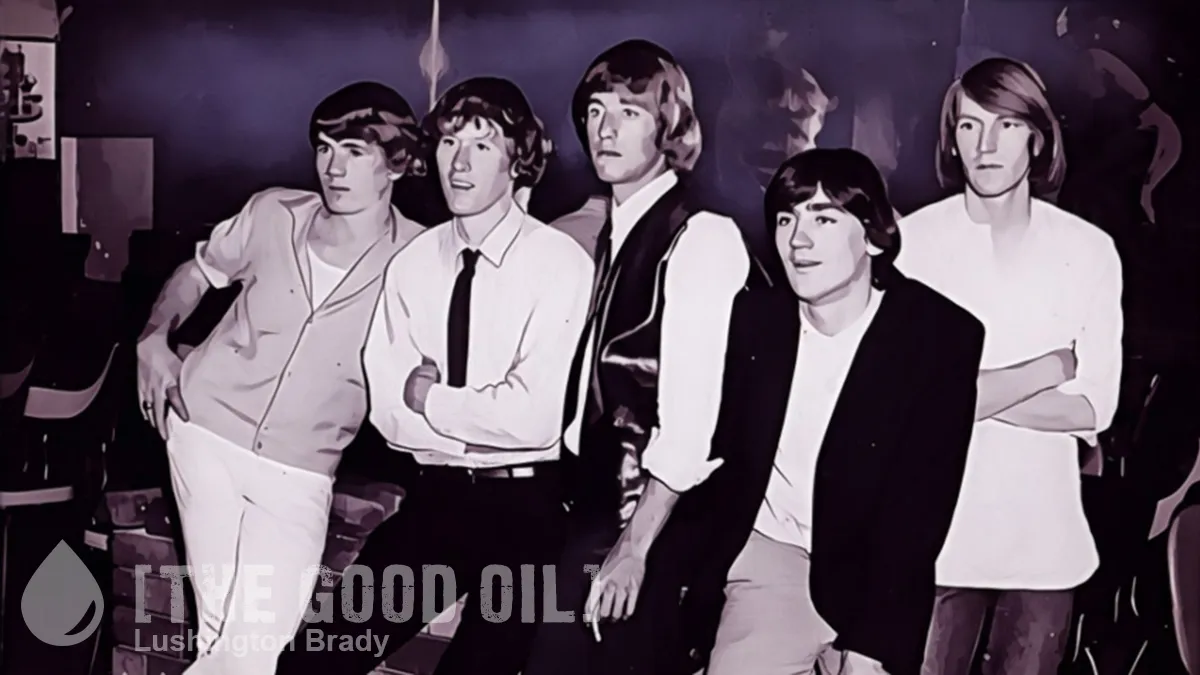

At the epicentre of this garage-rock storm were Sydney’s Missing Links. Formed in 1964, their brief but incendiary existence produced some of the wildest, most primitive records of the decade. Their 1965 single “Wild About You” was a feral, fuzzed-out anthem that later became a garage classic, covered by the Saints over a decade later. With long hair, feedback-drenched guitars and onstage antics that included instrument smashing and climbing the walls of venues, the Missing Links shocked polite audiences used to neat pop harmonies. They were, in every sense, proto-punk avant la lettre – too wild for radio and too abrasive for commercial success, but decades ahead of their time. For instance, they experimented with back-tracked guitars and six-minute singles, before even the Beatles.

In regional cities, too, new, wilder bands were springing up. In Bathurst, New South Wales, the Black Diamonds were developing their own strain of primal rock energy. Their 1966 single “I Want, Need, Love You” was an astonishing blast of fuzz guitar and manic rhythm, sounding like it had been recorded inside a jet engine. Even today, punk muso friends discovering the song were astonished that such a song came out of mid-’60s Australia. The follow-up, “See the Way”, retained the same ferocity. Though they never achieved national fame, the Black Diamonds embodied the spirit of the Australian garage underground: raw, unpolished and urgent. Their music captured the sense of isolation that haunted regional youth scenes, where rock and roll was not a career but an act of rebellion against small-town conformity.

Rural Victoria contributed the Elois, formed in Maryborough before being convinced to relocate to Melbourne by a radio DJ. The band released a couple of stunning singles and blew Melbourne audiences’ minds (and ear drums) with their fast, loud and feedback-heavy shows. With modest chart success, the band soon returned to small town of Maryborough and eventually disbanded.

Last, loneliest New Zealand wasn’t to be left out. Following the career path that generations would beat for another couple of decades, the Chants and the La De Da’s crossed the Tasman. The La De Da’s “How Is the Air Up There?” combined R&B roots with a fierce, aggressive edge that would have been at home in the Punk Explosion a decade later. The group’s live performances became legendary for their intensity and volume, culminating in the monumental concept album The Happy Prince (1969), which fused psychedelic experimentation with proto-heavy rock dynamics. Vocalist Phil Key and guitarist Kevin Borich pushed their instruments and voices to new extremes, earning a reputation as one of the most formidable live acts in the country. The La De Da’s were pivotal in transforming garage bands into full-fledged rock powerhouses, bridging the gap between beat music and the blues-based hard rock that would soon dominate Australian stages.

But no single person better personified this transformation of Australian rock’n’roll than Billy Thorpe. In the early ’60s, Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs were a clean-cut pop outfit: all neatly pressed suits playing the latest surf-tinged hits on Bandstand on the telly. Before the decade was out, though, Thorpe had transmogrified into the last thing you’d take home to mother: a long-haired, leather-clad, rock’n’roll Viking, rockin’, rollin’ and rootin’ across the land like a barbarian horde armed with guitars turned up to fuse-blowing volume (cameramen on ABC-TV’s GTK complained that the sheer volume of the band kept shaking the tubes in their cameras out of focus).

Under the influence of the Vietnam protests, counterculture, psychedelia and a whole lotta sex’n’drugs’n’rock’n’roll, Thorpe had torn through his previous clean-cut image. By 1969, the new Aztecs were one of the loudest bands around, notorious for their earsplitting live shows. Their transformation was fully realized at the Sunbury Pop Festival in 1972, where Thorpe’s commanding performance of “Most People I Know (Think That I’m Crazy)” cemented his status as Australia’s first true rock god. The song, equal parts defiant and self-aware, became an anthem for a generation disillusioned with mainstream culture. Thorpe’s shift from pop to proto-heavy rock mirrored the journey of Australian music itself – from imitation to self-determination; from polite harmony to raw power.

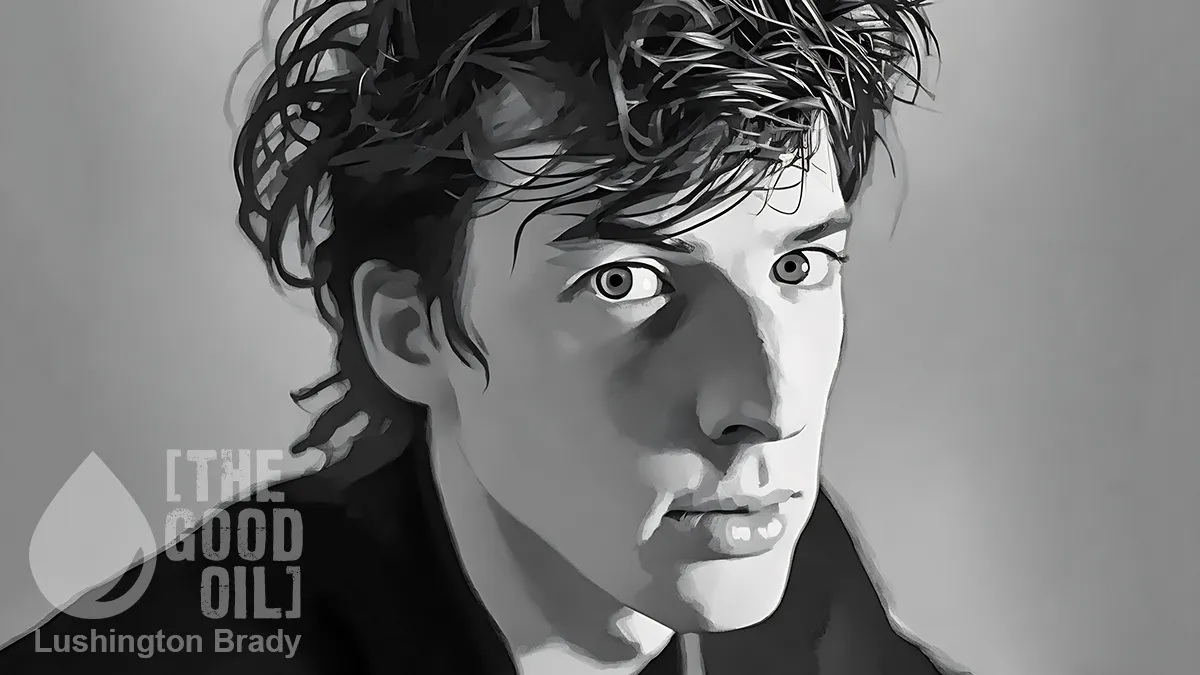

There was one other influence that was key to Thorpe’s transformation though: John Baslington Lyde, aka Lobby Loyde. The Man Who Taught Thorpie How to Play was a fellow Queenslander, indeed an old school-mate of the Aztecs’ frontman. If Thorpe was Australia’s first Rock God, Loyde was its first Guitar Hero.

Loyde was one of the first Australian guitarists to explore distortion as a creative tool rather than an accident. His early bands, the Purple Hearts and the Wild Cherries, were at the cutting edge of Australian R&B and garage experimentation. The Purple Hearts’ “Early in the Morning” (1966) and “Of Hopes and Dreams and Tombstones” (1966) combined blues grit with a snarling attitude that prefigured punk’s disdain for polish. Loyde’s guitar tone – thick, abrasive and heavily overdriven – became a signature sound that countless bands would emulate.

With the Wild Cherries, Loyde moved further into psychedelic and experimental territory, producing singles like “Krome Plated Yabby” (1967), which fused heavy riffing with surreal lyrics. But it was his work with Billy Thorpe and later with his own band Coloured Balls that would define his legend. Coloured Balls’ 1973 album Ball Power captured the full force of his guitar vision: heavy, riff-driven and defiantly uncommercial. In many ways, Loyde bridged the gap between the 1960s’ garage pioneers and the 1970s’ pub rock and punk explosions. His influence extended through the next decade, mentoring younger musicians and proving that raw sound and authenticity could trump fashion.

Through the ’70s, the energy of these bands matured and diversified. The Great Australian Boogie emerged and so did Prog Rock. Bands like Buffalo pushed the hard rock into a proto-metal sound similar to Black Sabbath (Buffalo supported Sabbath on their first Australian tour in 1971). But the wild energy and stripped-back aggression of the late ’60s endured, inspiring the underground punk scenes emerging across Australia, not least in Queensland.

Between the oppressive, corrupt Bjelke-Petersen government and the rock antics of Thorpie and Loyde, something in the water up north gave birth to one of the first bona fide punk songs in the world (beaten by the Ramones by only a few months and predating anything from London). The Saints’ “(I’m) Stranded” was born out of Brisbane’s repressive mid-’70s milieu, but it carried the DNA of the Missing Links, the Black Diamonds and the Purple Hearts.

Similarly, compilations such as Ugly Things, Devil’s Children and Down Under Nuggets, in the spirit of the hugely influential Seeds and Nuggets compilations in America, brought songs and bands that had long been out of print to another generation of wide-eared musicians but also cemented the recordings in their due place in rock history. Critics now recognize that Australia’s garage scene was not a pale imitation of American or British trends, but an authentic, parallel, development. The urgency, fuzz and swagger of bands like the Missing Links and the Black Diamonds were proto-punk in spirit if not in name. In half a decade, Australian rock evolved from mimicry to mastery. What began as teenage defiance in suburban garages became a national statement of identity: loud, rough-edged and unapologetically Australian – raw, unfiltered and forever wild about you.