Table of Contents

SophiaPhobia

I was dismayed to read in Stuff that Maori and Pasifika patients will be given priority on elective waiting lists at Wellington District Health Boards. Of course, I’d love for Maori and Pasifika people to achieve similar health outcomes as the population generally, but is this the way to achieve that outcome? Or is the initiative based on faulty reasoning and, arguably worse, hidden politics?

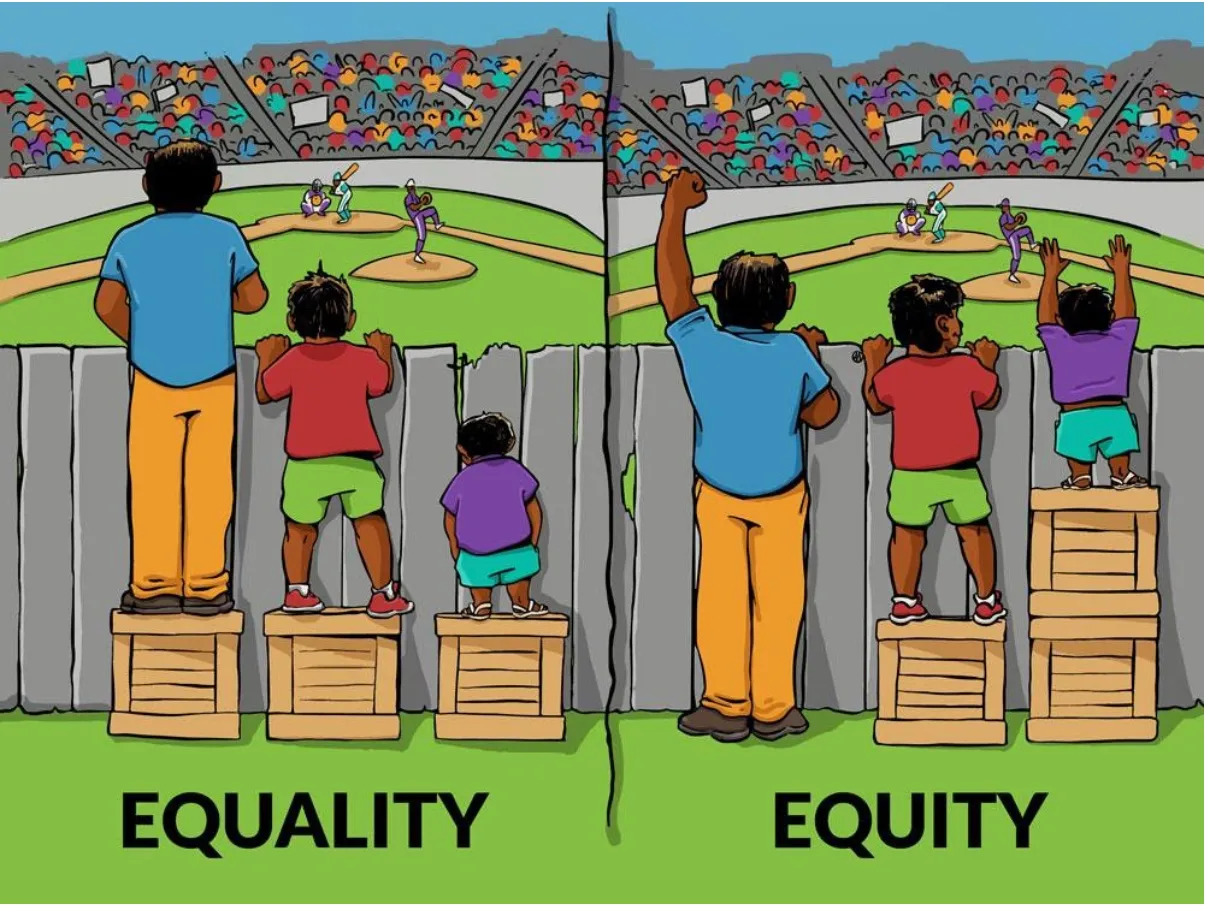

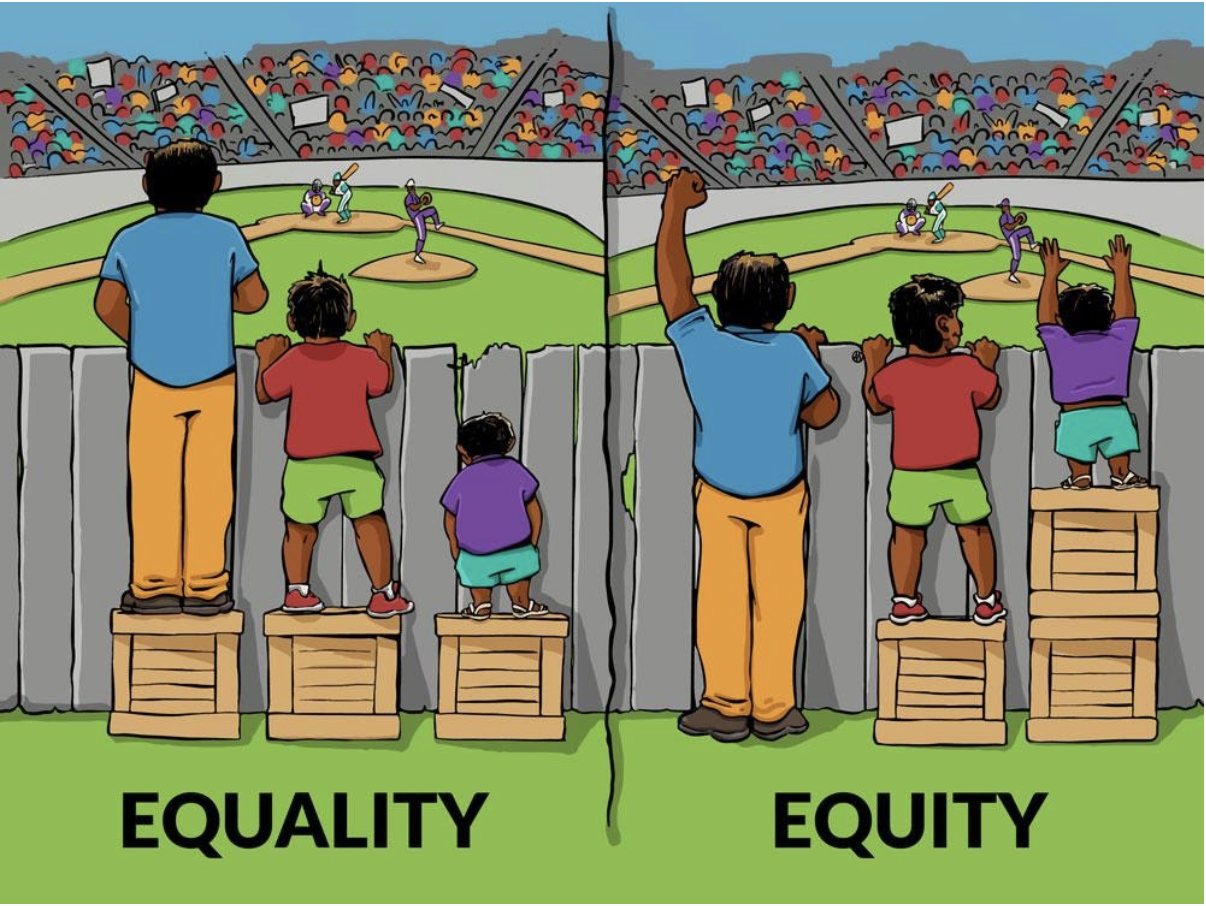

According to the article and my sources in a smaller DHB, “equity” is all the rage. In training materials, the “equity” concept is presented by way of a cartoon analogy.

The implications are obvious: some people in the community need to be given an extra boost so that we all have the opportunity to “watch the game”. The Ministry of Health’s view is that Maori and Pasifka people have a greater need than the population as a whole. It follows that in a socialist system, they must be given a boost: in this case priority in the elective waiting list.

But this argument via an analogy is faulty at multiple levels. The one that I find most disquieting is the echo of communism. Marx writes in Critique of the Gotha Program:

From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

The problem with this, as with much of Marxism, is: who decides what abilities one has and more importantly, who decides what needs we have?

Furthermore, argument by analogy is one of the weakest kinds of argument. Two minutes thinking about the cartoon and one starts seeing the problems. First, the only thing needed to correct the inequity in the cartoon is a change in stature. But Maori and Pasifka health outcomes have complex and systemic causes not limited to income, housing quality, diet, exercise, fatherlessness, violence, smoking and drug use and, yes, genetics.

Such complexity cannot reliably be analysed by central planners so that they know what is needed to boost those in greater need. The problem of complexity is fivefold for central planners. First, they cannot list all the contributing factors to health outcome because there is always a risk that they have missed one. Second, they have only a limited idea of how all those factors interact to create the health outcome. Third, the interaction is probably inherently “non-deterministic” – a mathematical concept that implies that even if you start with the same factors you can end up with a different outcome. Fourth, there are theoretical reasons to think that true equity will never be reached because of the second law of thermodynamics (that discussion is beyond the scope of this article). And lastly, even if all the above problems are overcome, it still could be politically unpalatable to put policies in place to change the factors.

Because of these problems, central planners — and evidently Wellington DHBs — think they can just skip to the answer. Instead of trying to affect the causes of inequity they can just fix the effect. But this will lead to even worse inequity. To see this, realise that ultimately someone still needs to decide who will get elective surgery. Suppose we have Mrs Smith and Mrs Jones both of whom need a hip replacement but there is only one funded surgery available. According to this policy, Mrs Smith will get the hip because she has ethnicity “Pasifika” according to the Ministry of Health database.

But here is the problem. According to the Ministry of Health, one can nominate one’s own ethnicity. No proof is needed, and you can have more than one. Once the general public realise this fact, everyone will claim Maori or Pasifika ethnicity in order to get a boost. Thus, the informational basis on which to give the “needful” group a boost disappears, and we are back to square one. Except now we are at square minus-one-hundred. Because now the Ministry has no reliable ethnicity data on which to attempt to form health policy. They have lost even their ability to differentiate among ethnic groups in the data.

All this is not to say that we should not try to improve the health outcomes of Maori and Pasifka people. We should. But we need to get back to working on the basics, namely the proven causes of poor health. One cause that is greatly neglected in government policy or even encouraged by current policy is fatherlessness. But I do not expect to see a change there as one of the greatest institutions that Marxism needs to destroy is the family. And Marxism is the hidden politics of this move.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.