Table of Contents

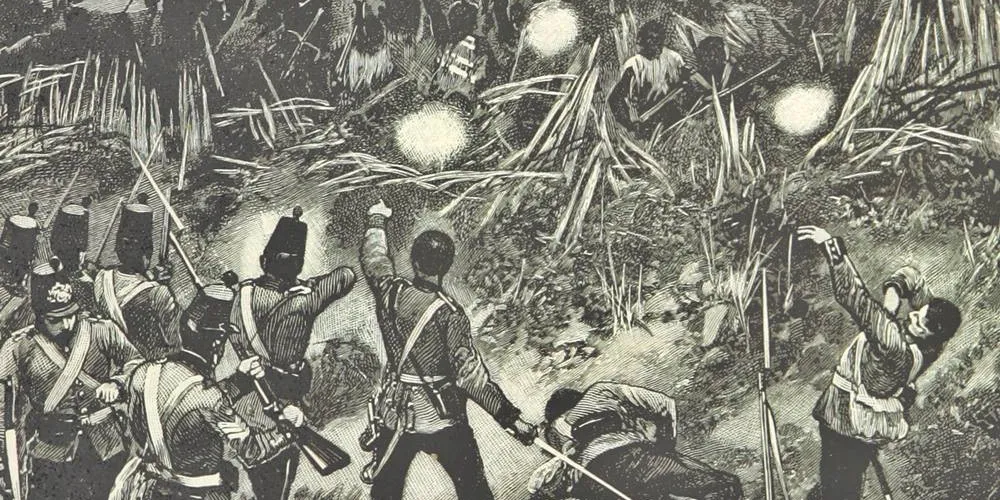

Those were the last words of Captain John Fane Charles Hamilton as he jumped into the fray to support a wavering force trapped in an ambush at Gate Pa in the Tauranga campaign of 1884. He was felled by a Kingitanga bullet moments later. Like many British officers, he charged into battle armed only with a sword, urging on his men from the front lines. The battle itself was a rout for the British, due to the tactical genius of chief Rawiri Puhirake and his military engineer Pene Taka Tuaia. Months later, colonial forces stormed the unfinished earthworks at Te Ranga to exact their revenge in a one-sided battle that left Puhirake and most of his men dead. Captain Hamilton’s regiment was later stationed on the Waikato, and his men named the swampy fort in his memory. The rest is history.

One may debate the merits of the Tauranga campaign and of the Kingitanga rebellion. There were certainly Englishmen and Maori who opposed both. One doesn’t have to pick a side: the missionaries argued against war, rebellion, land confiscation, and any other injustice they saw. For Puhirika, the fear that the British would take the land of his people led to their justification for doing so. For Captain Hamilton, the call for the crew of the HMS Esk to assist local troops was a routine commission that cost him his life.

In all the hubris around the removal of statues, Captain Hamilton’s case stands out, as his monument was removed for the novel crime of simply being too white. Many historical figures can be complicated and colourful, but Captain Hamilton was neither of those. One can understand the shrewd capitalist who changes the colonial name of his business to more easily profit from the 21st-century bourgeois, one can understand a liberated people destroying the symbols of their tyrannical dictators, and one can understand the contempt for unsavoury memorials, but the animosity towards Captain Hamilton requires some more context to properly comprehend.

In cultural Marxism the idea of critical theory has become prominent in recent years. This is a materialistic worldview that sees only power structures and an eternal class struggle between the oppressed and the oppressors. Largely an American import, this view pits “whiteness” (oppressor/perpetrator) against “blackness” (oppressed/victim). It’s a depressing system that requires you to find ways to become the greatest victim ever.

Captain Hamilton was an ordinary Englishman, a Christian, a faithful subject of the Crown, a decorated and gallant officer, and a soldier who gave his life for his country. That makes him the very embodiment of “whiteness” to those who follow cultural Marxist ideology. He spent only a few months stationed in New Zealand and never fired a single shot—not that it would have been a problem if he had. He was part of a system and therefore bears full responsibility for all the faults of that system. These are sins that can only be atoned for by “decolonisation” (complete destruction) of that system and all it stands for and the erasure of his memory. That’s why Captain Hamilton’s statue was sent packing.

There are thankfully few people who believe this, but ironically they tend to hold positions of power. This view is largely limited to a handful of professional race-baiters, left-wing bureaucrats, Marxist professors, and an MP who wants to do to our country what her comrades did to her birthplace. It’s not about race, injustice, or even colonisation, this is just a thin pretext to hang their hatred for the Christian west on.

All this rewards an ignorance about the past and results in a society that loses the imaginative capacity to understand its own roots. The Christian themes of forgiveness and reconciliation are replaced with bitterness and envy that can never be satiated.

Usually a statue is erected to celebrate a victory, and so was Captain Hamilton’s: a commercial victory marking the 75th anniversary of the Gallagher Group in 2013. The local company gifted the city a statue in the likeness of its namesake. If it did commemorate war, as claimed by some, it would be for a Maori victory and a colonial defeat.

In the end, statues are just metal or stone and can always be replaced. I can be thankful that these events had led me to a brief study into the origins of Hamilton and Tauranga, giving me a greater understanding of our rich history and heritage. I can now teach these stories to my children when we visit these places. Maori and Pakeha nationalists can always put the statues back up once the Marxist poison has been purged from our green and pleasant land.

John Hamilton and Rawiri Puhiraki both lie buried at the same military cemetery in Tauranga. Hamilton is remembered for his gallantry and Puhiraki for his chivalry. Puhiraki’s memorial ends as follows:

“The seeds of better feeling between the two races thus sown on the battlefield have since borne ample fruit: disaffection has given place to loyalty, and hostility to friendship, British and Maori now living together as one united people.”