Table of Contents

Communist China is the most rigorously atheist country in the world. Which should hardly be surprising: Communism is a jealous god, after all. As an ideology of total control, communism simply cannot tolerate rivals for the minds of its subject populations. The Soviet Union similarly crushed the churches.

China still persecutes religions violently, whether it’s the Islam of Xinjiang’s Uyghurs, or the Falun Gong.

Yet, tragically, China had – had – a long history of some of the great religions of the world.

China, for instance, gave the world the religion and philosophy of Taoism (or Daoism). Taoism is not necessarily a religion, although much of it is rooted in the folk religion of rural China. Like Buddhism, it can also be studied as a non-religious philosophy.

The primarily idea and focus of Taoism is the Tao (way, path), which is important to be followed, not taking any action that is contrary to nature and finding the place in the natural order of things.

Alan Watts’ classic treatise on Taoism is subtitled “the watercourse way”: water imagery is abundant in Taoism. While Taoism can mistakenly be seen as a creed of apathy, it teaches that the “way” is that of water. A famous Taoist parable tells of an old man who fell into a torrent. When he eventually emerges unscathed, he explains to incredulous observers that, “I accommodated myself to the water, not the water to me. Without thinking, I allowed myself to be shaped by it. Plunging into the swirl, I came out with the swirl. This is how I survived.”

Another Taoist parable talks of a farmer (nature imagery is ubiquitous in Taoism) whose neighbours alternately commiserate and congratulate him on the ups and downs of his fortunes. To every “How unfortunate!” and “How fortunate!”, the farmer stoically replies, “Maybe”.

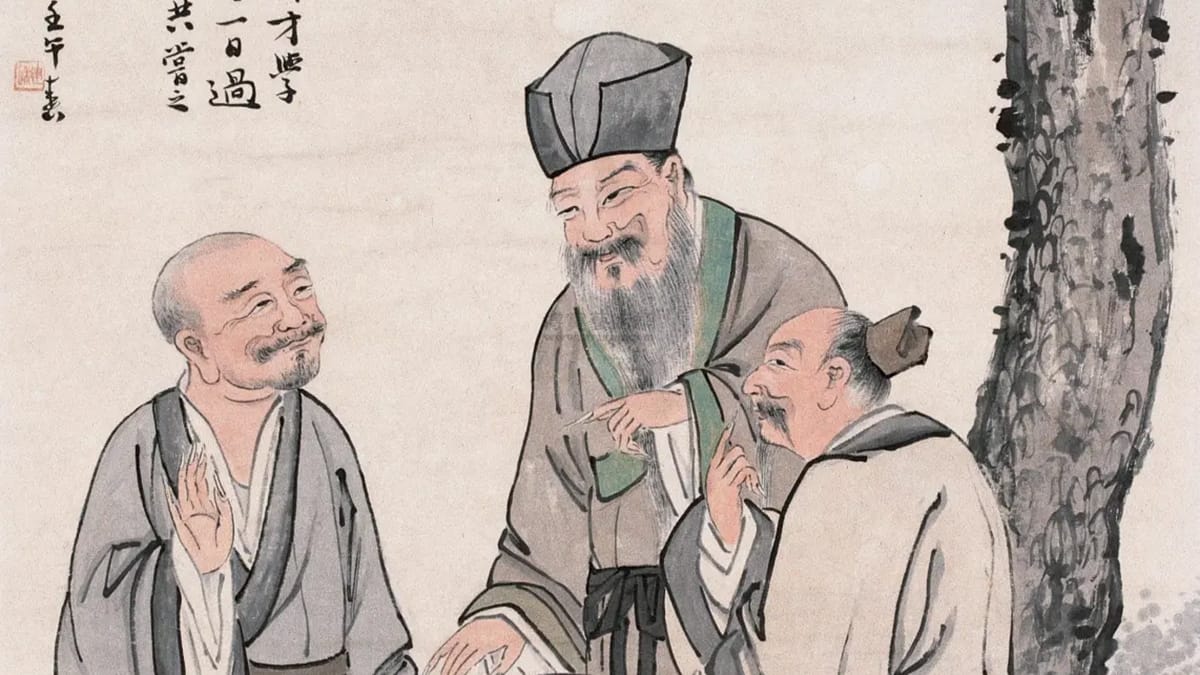

In a famous and much-copied Chinese painting, The Vinegar Tasters, Confucius, Buddha and Lao Tse are tasting a barrel of pickling vinegar.

Confucius has a sour expression, because, he says, the vinegar is soured wine, and sees it in need of correction, just as society should be maintained through strict rules. Buddha has a bitter expression, because the vinegar is bitter: an example of the suffering of life.

But Lao Tse smiles and says: “Now this tastes like vinegar – and that’s how vinegar makes pickles!”

Perhaps the closest analog to Taoism in Christian literature is the Book of Ecclesiastes:

What profit does a man have from all his labor at which he labors under the sun?… To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven… All the rivers run into the sea, yet the sea is not full; to the place where the rivers go, there they go again.

The roots of Taoism can be traced to Lao-tzu and his text Tao Te Ching (the Classic of the Way and its Power), dated to the 6th century BC, however, the teachings in the text are older […] The Tao-Te-Ching is a book of poetry that explains how to live in peace with the world. Other philosophical texts are the Chuang-tzu (4th century BC), Huai-nan Tzu (2nd century BC), and Lieh-tzu (3-4th century AD).

At the end of the Han dynasty, the first schools of religious Taoism were opened.

About History

Another major religion that long shaped the course of Chinese culture and history is Buddhism. Buddhism is not native to China, though: just as Christianity came to Europe from its birthplace in the Middle East, Buddhism came to China from its home in India.

The practice of Buddhism spread in the centuries after the death of Gautama Buddha through the actions of pilgrims, wandering evangelists and strong believers who wished to spread the faith to remote lands and also through observation of Buddhist practices by those who traveled overseas from India and Sri Lanka. The various routes that composed the Silk Road were important conduits for Buddhism making its way into China, more so than the maritime routes that were more influential in the transmission of the belief into Southeast Asia. Buddhism was recorded as being present in China from the time of the Han dynasty, and according to legend, the emperor Mingdi (Ming-ti, 57-75 CE) received a divine vision that inspired him to seek out knowledge of the Buddha from India.

One of the most beloved classics of Chinese literature, Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West, tells the story of the monk Tang Sanzang, or Tripitaka, who accompanied by the Monkey King and other magical disciples, travels to India to obtain sacred Buddhist texts.

Chinese monks and scholars were dispatched at regular intervals to seek out Indian knowledge and texts that could be brought back to China and translated into the Chinese language. In nearly every case, when Buddhist concepts were introduced to China they were combined with preexisting Chinese religious concepts or else were subsequently modified. Notably, Buddhism was combined with the Daoist (Taoist) philosophy of Laozi (Lao Tzu), both to show respect to the latter and also to make the new, foreign concepts more intelligible to a Chinese audience. The sheer size and degree of diversity within China meant that variations in interpretation inevitably occurred.

Several distinct schools of Buddhism consequently emerged in China:

The Tiantai school taught that existence was real but impermanent and insubstantial and the need to adhere to the middle path in the search for personal enlightenment […] Tiantai Buddhism was introduced into Japan at the beginning of the ninth century under the name Tendai by the monk Saicho […]

The Avatamsaka school of Buddhist thought is known as Huayan in China and Kegon in Japan […] the basis of Huayan Buddhism is that all elements of reality depend on each other and arise because of each other, spontaneously. At every moment an infinite number of possibilities exist, and it is possible, therefore, for an infinite number of Buddhas (who can internalize all of the possible variations within a harmonious whole) to emerge into the world […]

The Pure Land form of Buddhism, known in Chinese as Qingtu (Ching-tu), is based on the Pure Land Sutra (Sukhavativyuha-sutra), which was created in the north of India in the second century CE. The sutra concerns the process of a monk who sought enlightenment by, in part, vowing to create a pure land in which all could live happily to a long and fulfilled age […] this form of Buddhism became very popular, largely because it offered the opportunity for ordinary people to aspire to enlightenment within their own lifetime […]

Zan Buddhism focuses on the role of meditation in the search for enlightenment. It is known as Dhyana Buddhism in Sanskrit and zen in Japan, where it reached its greatest level of popularity. The Indian monk Bodhidharma brought it to China in 520 CE. Zan Buddhism is centered on the belief that all living creatures have within themselves an aspect of Buddhahood and that it is possible, through intensive meditation, to realize this existence, which results in wu, or enlightenment.

About History

With such a rich history of religious and philosophical traditions, it is one of the great tragedies of China’s long history that they have all been crushed by another introduced, foreign religion: communism.