Table of Contents

Chris Trotter

Democracy Project

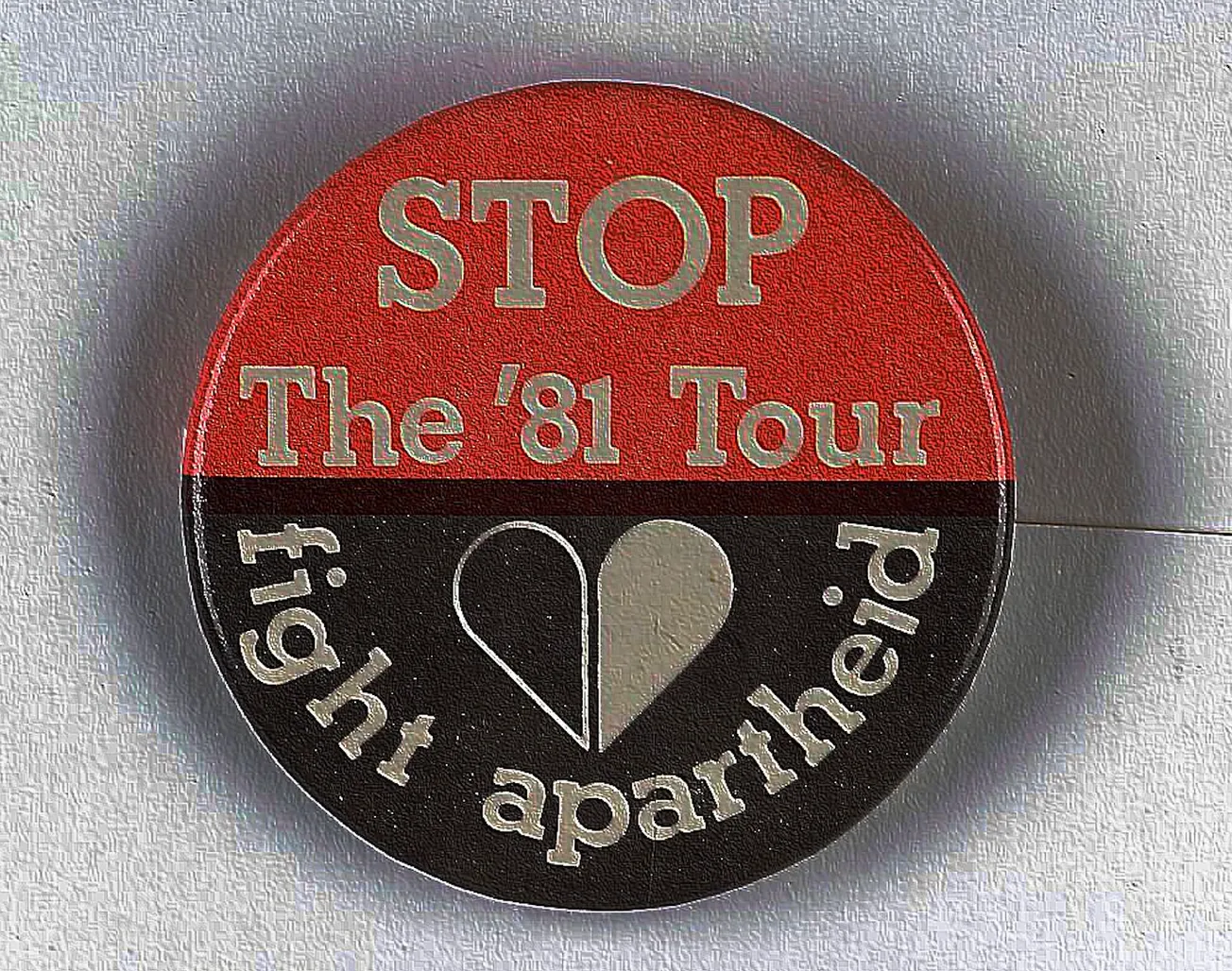

As angry Trump supporters filed out of the Butler showgrounds, many paused to hurl abuse at the media pack. As they vented their anger upon the assembled “mainstream” journalists, I couldn’t help recalling the behaviour of an even angrier crowd as it filed out of Hamilton’s Rugby Park in 1981.

Tens-of-thousands of Waikato rugby fans had turned out to watch their team take on the Springboks. When the actions of anti-tour protesters caused the game to be called off they were furious. The abuse they hurled at the broadcasting box, along with unopened cans of beer, reflected their instinctive grasp of the media’s power to shape political perceptions. The rugby fans knew in their gut that what had just happened would be reported to the advantage of the anti-tour activists, and to the disparagement of New Zealanders like themselves – hence their fury.

When he learned, through friends and media reports, of the violence that had swept through Hamilton following the cancellation of the Waikato-Springboks match, the eminent, Austrian-born, left-wing economist, Wolfgang Rosenberg, who lectured at the University of Canterbury, observed that it reminded him of Kristallnacht (generally translated as “night of broken glass”) when, on 9-10 November 1938, Hitler’s Nazi regime attacked Germany’s Jews, burned their synagogues and smashed the windows of their businesses.

News of Rosenberg’s dramatic comparison swept through the ranks of the anti-tour movement, further lifting its morale, and conferring a powerful historical dignity upon what had been a frightening and painful (albeit non-fatal) political experience. Rosenberg’s comparison did something else. Wittingly or unwittingly, this refugee from 1930s Austria had compared pro-tour New Zealanders to the Nazis who perpetrated Kristallnacht. A struggle against the importation of South African racism had been upgraded to a struggle against fascism.

Liberal journalists found it almost impossible to resist this significant redefinition of the moral issues at stake in the already deeply divisive Springbok Tour. The principal inspirers of the anti-tour movement were no longer the stubborn Ces Blazey, chairman of the New Zealand Rugby Football Union, and his chief political enabler, Prime Minister Rob Muldoon. Now they were fighting the good fight against the fearsome shadow of Hitlerism itself. Those who supported the tour ceased to be simply misguided, and became, instead, the representatives of a much darker system of belief.

In taking on this Manichean aspect, the most significant factor in the police decision to call off the Waikato-Springbok game faded rapidly from public consciousness. Commissioner of Police, Bob Walton, had been made aware that a stolen light aircraft, piloted by an anti-tour activist, was en route to Rugby Park, and that if the game was not called off, the plane would be flown into the main stand – killing and injuring hundreds of human-beings.

This was a terrorist threat, pure and simple, and Walton could not be sure that the pilot was bluffing. The likelihood that the man at the aircraft’s controls would actually carry out his threat may have been low, but it wasn’t zero. And if the Police Commissioner made the wrong call he would be guilty of failing to prevent an unprecedented national calamity. Not surprisingly, Walton ordered the game’s cancellation and the evacuation of the stadium.

It is worth pausing and reflecting upon this extraordinary incident. In the years after 1981, the pilot of the aircraft became a sort of folk hero. He had presented the police with a bluff which they could not possibly call. The game was abandoned, the plane landed safely, and nobody in the stands was hurt – win/win. But, paying the blackmailer does not render extortion any the less reprehensible. Walton capitulated because there were hundreds of helpless men, women, and children being threatened with death, and he was not morally entitled to gamble with their lives.

Since 1981, the anti-tour movement has sought refuge in the age-old argument that the end justifies the means. But when the means encompasses turning human lives into bargaining chips there is no justification. It doesn’t matter that the pilot, an RNZAF veteran, would never have carried out his threat. Walton didn’t know that, and the man flying the plane wasn’t about to tell him. He needed the Police Commissioner to be terrified of what he might do, and he used that terror to secure his political objective. That is the definition of terrorism.

This article was originally published by the Democracy Project.