Table of Contents

GOVERNMENT COMES TO NEW ZEALAND

The Governor of New South Wales wants to appoint a “British Resident in New Zealand” (a position transplanted from colonial India), to go with the Justice of the Peace already appointed. The British Secretary of State approves. James Busby, a grape grower from New South Wales is appointed. He is to capture escaped convicts, protect settlers and traders from the Maori and the Maori from settlers and traders, and encourage the Maori to accept British-style government.

He arrives in 1833. He has nobody to help him do this capturing and protecting. He is only one man in a house at Waitangi, Bay of Islands, with a letter from the British government to the Maori chiefs telling them he will “prevent outrages” and “punish perpetrators”; and a letter from the New South Wales Governor telling him he has “no legal power or jurisdiction”. The first thing he does is plant grapevines.

The second thing he does is quite remarkable. It’s the start of some quite remarkable government things done in New Zealand by some completely inexperienced and otherwise unremarkable non-government people who suddenly have a government job. The grape grower calls a meeting.

The First Meeting at Waitangi, March 1834

This is the first order of official government business ever conducted in New Zealand, despite the fact that the British position on New Zealand at this time is quite confusing and contradictory. It’s a complicated affair.

Ships from New Zealand trading with New South Wales had no national flag to fly under. They could not be British as New Zealand was not officially British territory. They could not register in New South Wales as New Zealand was not (yet) part of New South Wales. They required a flag of their own to sail under in order to be permitted to enter Australia.

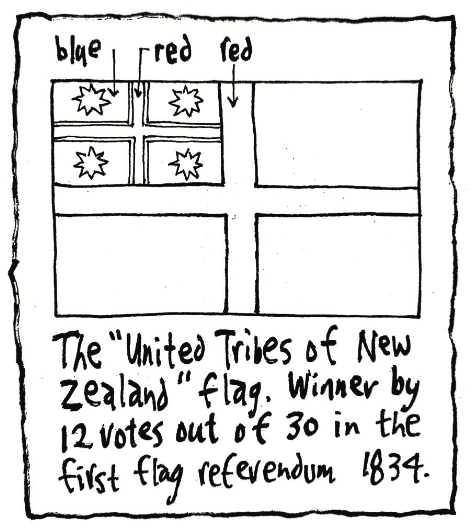

James Busby, the British Resident in New Zealand, suggests to the New South Wales Governor that New Zealand should get a flag (1833). New South Wales sends over a design for a flag with four blue horizontal bands on a white background with the Union Jack in the top left corner.

But Busby does not like this flag as he says the flag should have some red in it as the Maori people quite like red. A missionary at The Bay of Islands draws up three flag designs and these are sent to Sydney. The Governor of New South Wales has them made up into flags, and the three flags are sent back to New Zealand.

The British Resident organises a meeting of northern Maori chiefs outside his house in Waitangi, in order to chose a national flag for New Zealand. Thirty chiefs attend. (It is not known how many “tribes” were represented, nor what their status was as “chiefs”.)

The Maori had no idea what a flag was and had never used one before, but they liked all three. When told they could only choose one, one flag gets 12 votes, one 10, one six, and two chiefs refuse to vote because they fear there might be danger in this flag business.

The winning design is a white flag with a red St. George’s cross; the top left quarter being blue with another red cross in it bordered in black, with four eight-pointed white stars, one in each quarter. When the flag is officially adopted in Britain in 1835 it is changed slightly. The red cross in the top left quarter is given a white border, not a black one; and the four stars are made five-pointed not eight-pointed.

It is known as “The United Tribes of New Zealand” flag, even though the “tribes” were never united (except perhaps as allies against other tribes), and it is not known how many “tribes” were actually represented to unite from the 30 “chiefs” who attended.

The whole thing was made-up by James Busby. The first instance of British government being transplanted onto Maori tribes, and Maori tribes being thought of in terms of British government. Either way, it wasn’t real (except to James Busby).

In the immediate Bay of Islands area there were some three tribes, with possibly two other tribes farther north, and two other tribes farther south, who could have attended from a region north of Whangarei and Kaipara Harbour (out of a total of some 49 North Island tribes). Irregardless of which “tribes” were represented, and what the status was of the “chiefs” who attended, they would certainly be more inclined to fight each other than be united (the northern tribes being especially warlike as the preceding pages have shown).

The British run up the new flag, give three cheers, fire off a 21-gun salute, and then sit down to lunch. The Maori are given a pot of cold porridge to share amongst themselves, without any bowls or spoons (or brown sugar and milk).

The Second Meeting at Waitangi, 28 October 1835 (also called The Waitangi Declaration)

The first meeting went so well that the British Resident gets another pot of porridge and calls another meeting, this time to get the chiefs to sign “A Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand by a Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand”.

It’s the second order of official government business to be conducted in New Zealand, and it’s an even more remarkable and complicated affair. Thirty-five (or 46) chiefs attend and sign, and 18 more sign later. The chiefs apparently came from an area between the Thames and North Cape. This could possibly have involved some 12 tribes at most. Again it is not known what “tribes” were represented, nor what the status was of the “chiefs” who attended.

Busby writes the document himself and has the missionaries produce a Maori translation. The grape grower is a diplomat. The reason for the declaration is to stop Baron de Thierry from setting up an independent French state in Hokianga (he’s more effectively stopped when he actually shows up in 1837). The action is not authorised by New South Wales or Britain. There is no Maori government. The United Tribes are not united. There is no Confederation of tribes. The independent territories of New Zealand are not defined. It’s another bit of made-up government business by James Busby. The power of pen and paper.

Nothing further happens. The Maori go home. The document goes in the file. De Thierry is not a threat. But Britain continues to get reports of tribal wars and lawlessness in New Zealand. British subjects and Maori are asking for protection (the Maori from themselves). The missionaries are calling for action. Busby calls the situation: ”The accumulating evils of permanent anarchy”. And in Britain, there is news that a private company has been formed to set up a colony in New Zealand with its own government.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part Two

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Three

- The British & the French in New Zealand: Chapter Five Part Four

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part One

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part Two

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part Three

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part Four

- The British Come to New Zealand For Good: Chapter Six Part Five

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.