Table of Contents

Ani O’Brien

Like good faith disagreements and principled people. Dislike disingenuousness and Foucault. Care especially about women’s rights, justice, and democracy.

Chlöe Swarbrick wants you to believe the government is intentionally increasing homelessness. She told RNZ’s Mata with Mihingarangi Forbes:

The only conclusion that I can really come to is that this government has intentionally increased homelessness…

It’s the kind of soundbite that plays well on social media. Outrage travels faster than nuance, and a short clip of a politician expressing moral disgust can ricochet around Instagram far quicker than a spreadsheet full of complex data. But the problem with this particular claim is that it’s not just hyperbolic, it’s deeply irresponsible. It also leans on numbers that don’t mean what she’s implying they mean, and are in no way comparable to the ‘homelessness’ figures quoted overseas. It’s a classic case of comparing apples with oranges.

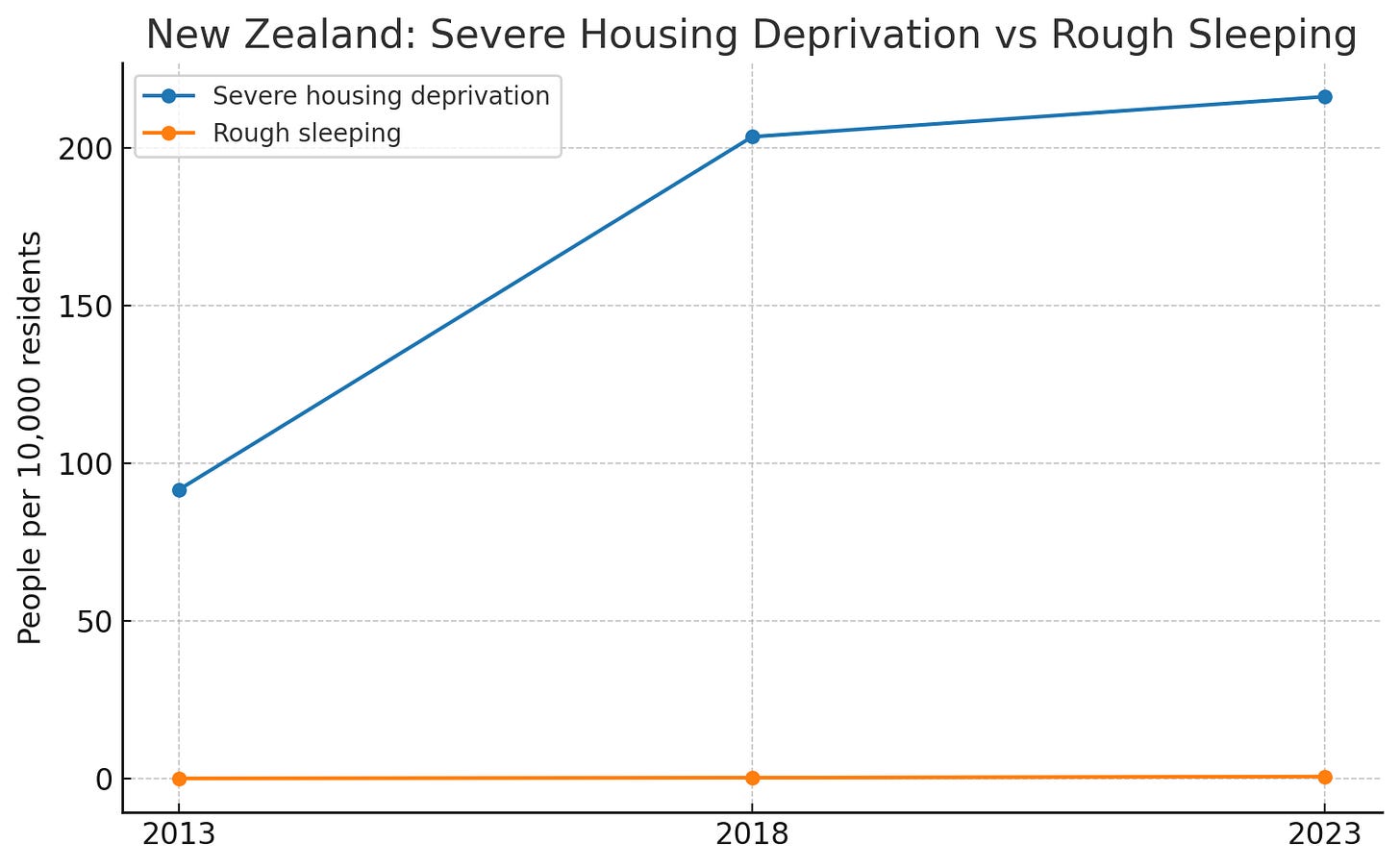

Statistics NZ doesn’t actually publish a ‘homelessness’ figure in the narrow sense that most OECD countries do. Instead, we have a measure called “severe housing deprivation”, which is much broader. It includes three groups: people without shelter (rough sleepers), people in temporary accommodation such as motels and night shelters, and people living in uninhabitable housing like garages or sheds. This is a useful measure for social policy, but it’s not what most people mean when they think of ‘homelessness’ in an international context.

The 2023 Census counted 112,496 people as severely housing deprived, about 2.3 per cent of the population. That sounds enormous, and it is, but it is also a stitched-together category that blends very different situations into one headline number. In reality, the number of people in New Zealand without shelter, the part comparable to “rough sleeping” overseas, was 333. That works out to 0.64 per 10,000 residents. In comparison, England’s rough sleeping snapshot in late 2024 recorded 4,667 people which is 0.83 per 10,000. In the United States, the figure was 256,610; a whopping 7.7 per 10,000. And Japan, with its famously low rate, recorded 3,824 rough sleepers at 0.31 per 10,000. Seen in that light, the ‘New Zealand is the worst in the world’ narrative starts to look shaky.

The data trends over the past decade or so also raise a political question that Swarbrick would rather not answer: if homelessness is, as she insists, a “political choice”, then what choices did her own party make when it was in government? From 2017 to 2023, the Greens were part of Labour-led governments. From 2020, her co-leader Marama Davidson was minister for homelessness. This was not a powerless position. It came with the mandate to coordinate agencies and deliver on the government’s much-touted Homelessness Action Plan.

Labour and the Greens’ record is sobering. Emergency motel use ballooned from fewer than 1,000 households in 2017 to over 4,000 by 2022. The public housing waitlist more than quadrupled, from around 5,000 in late 2017 to over 24,000 by the time the government changed. Despite this surge in emergency housing, rough sleeping numbers didn’t fall significantly and in some areas they worsened. The Greens had the portfolio, the budget, and the mandate, but they didn’t deliver any measurable reduction in the most acute forms of homelessness. If the test is whether political choices can reduce homelessness, then the Greens’ own tenure is Exhibit A in how hard it is to turn lofty rhetoric into results.

That’s not to say New Zealand’s housing crisis isn’t real: it is, and it is complex. We have a chronic undersupply of affordable housing, a problem decades in the making. We also have a long-term lack of effective wraparound services for those with complex needs like addiction and mental illness, meaning housing alone often isn’t enough. Our emergency accommodation system was turned into semi-permanent housing by the Labour government for thousands of families, without the exit strategies to move them into stable homes. And now, when Minister for Emergency Housing Tama Potaka busts a gut to get families out of motels and into stable housing, the architects of the problem disparage him from the opposition benches.

Regional disparities also mean smaller towns are experiencing rent spikes as people are displaced from cities. These are hard, structural problems that require unglamorous, sustained policy work, not viral one-liners from a privileged and out-of-touch career politician on her soapbox. This government is getting stuck in, but they have had less than two years to create change. Where they have see huge improvement in emergency housing, roughsleeper data isn’t as good.

According to the government’s own Homelessness Insights report, 141 people were recorded rough sleeping nationwide between January and March 2025. That’s a 24 per cent increase on the same quarter in 2024. In Auckland, however, the change has been more dramatic: outreach providers counted 809 people sleeping in cars, parks, and on the streets by the end of May, up from 653 in January and almost double the 426 recorded in September 2024.1

This surge isn’t isolated to the big smoke. Porirua’s point-in-time count rose from seven rough sleepers in March 2024 to 18 a year later. In Christchurch, outreach services dealt with 270 new clients in the six months to March 2025, compared with 156 in the previous half-year. Taranaki’s numbers jumped from 10 in June 2024 to 35 by December. The geography of rough sleeping is shifting, spreading beyond the traditional hotspots, but the actual numbers are still relatively low when taken at face value.

None of this is good news, but it does show the reality is more complex than the Greens’ sweeping claims. The problem is acute in certain cities, especially Auckland, and far less so nationally. For all the noise about “deliberate” increases, the data suggests a mix of factors: worsening housing affordability, mental health and addiction issues, migration pressures, and a shortage of transitional housing. Solving this will require targeted interventions, not just the kind of one-size-fits-all outrage that’s easy to post online but much harder to turn into results.

One of the most difficult truths in tackling rough sleeping is that not everyone on the streets wants, or is ready, to be helped. Outreach workers know this well. Some people have tried emergency housing before and for whatever reason prefer to be on the street. Others are dealing with deep trauma, addiction, or mental illness and find the routines and rules of supported housing overwhelming. For a small but significant number, the streets feel like a place where they retain control over their lives, even if it comes at the cost of security and comfort.

This doesn’t mean we should give up on people, but it does mean recognising that homelessness isn’t always solved by simply offering a bed. The most entrenched rough sleeping often requires months or years of consistent, trust-based engagement, sometimes with repeated offers of help before they’re accepted. It’s not enough to build housing: we need to build the relationships, mental health services, and addiction treatment pathways that make moving inside a genuine and sustainable choice. Anything less is wishful thinking disguised as policy.

The Greens like to present themselves as champions for tenants and the homeless, but some of their flagship policies and political positions have almost certainly made the housing crisis worse, or would if they were given the opportunity to implement them. The intentions might be noble, but, in housing, intentions mean very little without a clear-eyed understanding of how supply and demand actually work.

Take their enthusiasm for rent controls and a rental ‘warrant of fitness’. On paper, these sound like a win for renters: better standards and stable rents. But economists and even some tenant advocates warn that strict caps on rent can lead landlords to pull properties from the market or avoid investing in upgrades. The result is fewer rentals available, even as demand remains high. That scarcity drives up competition and forces more people into precarious housing situations.

The Greens have also been happy to block or oppose efforts to speed up the delivery of new housing. Their opposition to this government’s Fast-track Approvals Bill, legislation designed to accelerate consenting for infrastructure and housing projects, delays the very developments that could ease supply shortages. If you’re serious about fixing homelessness, you need more houses built faster, not more bureaucratic bottlenecks.

Even their tenancy reforms suffer from the same blind spot. Improving tenants’ rights is important, but without policies to increase the total stock of affordable housing, these changes just reshuffle the existing shortage. And while their tax policies, like tightening the bright-line test, aim to reduce speculative buying, they risk deterring investment in large-scale rental projects unless matched by aggressive public housing construction.

The Greens are too often the NIMBY party too. Whether it’s opposing medium-density housing rules in leafy suburbs or objecting to fast-track approvals for new builds on the grounds of ‘community character’ or ‘heritage’, the effect is the same: fewer homes where they’re most needed. This kind of localised obstructionism dresses itself up as environmentalism or community consultation, but in practice it protects high-value neighbourhoods from change while forcing growth and intensification into poorer areas. It’s an ugly contradiction for a party that claims to champion fairness and housing justice.

The Greens are right to care about the human cost of homelessness and housing insecurity. But as their time in government showed, you can’t regulate and redistribute your way out of a housing crisis while ignoring the basic math of supply. Without building more homes at pace well-meaning reforms risk making the problem worse.

Hyperbolic claims like Swarbrick’s are seductive because they present the problem as simple and the villains as obvious. But they also erode public trust in serious debate. When the language turns apocalyptic, compromise becomes impossible, and policy becomes a political football. Worse, it absolves those making the claim from explaining their own record when they had the power to act.

If homelessness truly is a political choice, then the Greens must own the choices they made between 2017 and 2023. Because the truth is this: it’s much easier to point fingers from opposition than it is to sit in cabinet and do the hard work of fixing the problem.

Chlöe Swarbrick has mastered the art of empty rhetoric: quick with a viral clip, heavy on moral posturing, and light on credible solutions. Her brand of politics thrives on outrage: framing complex social problems in simplistic, accusatory terms that cast opponents as villains and her side as the only morally acceptable choice. It’s a style that plays well on Instagram and TikTok but corrodes serious policy debate – replacing problem-solving with point-scoring. By leaning on exaggerated claims, cherry-picked statistics, and the constant implication of bad faith in her opponents, she fuels a toxic, polarised political climate that leaves no room for nuance and no incentive to actually fix the issues she campaigns on.

Data caveats (why the numbers don’t match)

If you’ve noticed that the “national total” of 141 rough sleepers for early 2025 doesn’t square with Auckland’s 809, you’re right, it doesn’t. That’s because they’re two completely different datasets.

The 141 figure comes from the government’s Homelessness Insights report for January–March 2025. It isn’t a full national headcount. It’s the number of people logged into a central reporting system by participating outreach providers in that quarter. Not all regions contribute, and not everyone encountered by services is recorded. Think of it as a minimum known to services, not the true number of people sleeping rough.

By contrast, Auckland’s 809 is from a dedicated city-wide street count in May 2025. It’s far more comprehensive for that region and if Auckland alone has over 800 people without shelter, the real national total is almost certainly in the thousands. This is why comparing one figure to the other without understanding the methodology will mislead you every time.

This article was originally published by Change My Mind.