Table of Contents

Steve Goreham

Steve Goreham is a speaker, author, and independent columnist on energy, sustainability, climate change, and public policy. More than 100,000 copies of his books are now in print, including his latest, Outside the Green Box: Rethinking Sustainable Development.

United States electricity prices are rising rapidly, up 18.1 per cent over the last two years. Renewable energy advocates claim that wind and solar installations produce cheaper electricity than traditional power plants, but power prices are rising as more wind and solar is added to the grid. In fact, electricity prices are soaring in leading wind energy states.

Over a 12-year period from 2008 to 2020, US average electricity prices rose only eight per cent, according to the US Energy Information Administration. This was much lower than the inflation rate of 20 per cent over the same period. But power prices rose five per cent from 2020 to 2021 and an additional 12.5 per cent last year. Most of this rise was due to rising US inflation, but the share of electricity generated from wind also rose from 8.4 per cent in 2020 to 10.2 per cent in 2022.

Headlines announce that electricity generated from renewables is lower cost. Scientific American stated in 2017, “Wind Energy is One of the Cheapest Sources of Electricity, and It’s Getting Cheaper.” In October, 2020 Bloomberg announced that “Wind and Solar Are the Cheapest Power Source in Most Places.”

It is true that the cost of building US wind and solar generating facilities has come down. Wind construction costs are down about 20 per cent since 2013 and solar construction costs have fallen more than 50 per cent, both approaching the costs for natural gas power plants. But construction costs are only part of the cost of electricity generation.

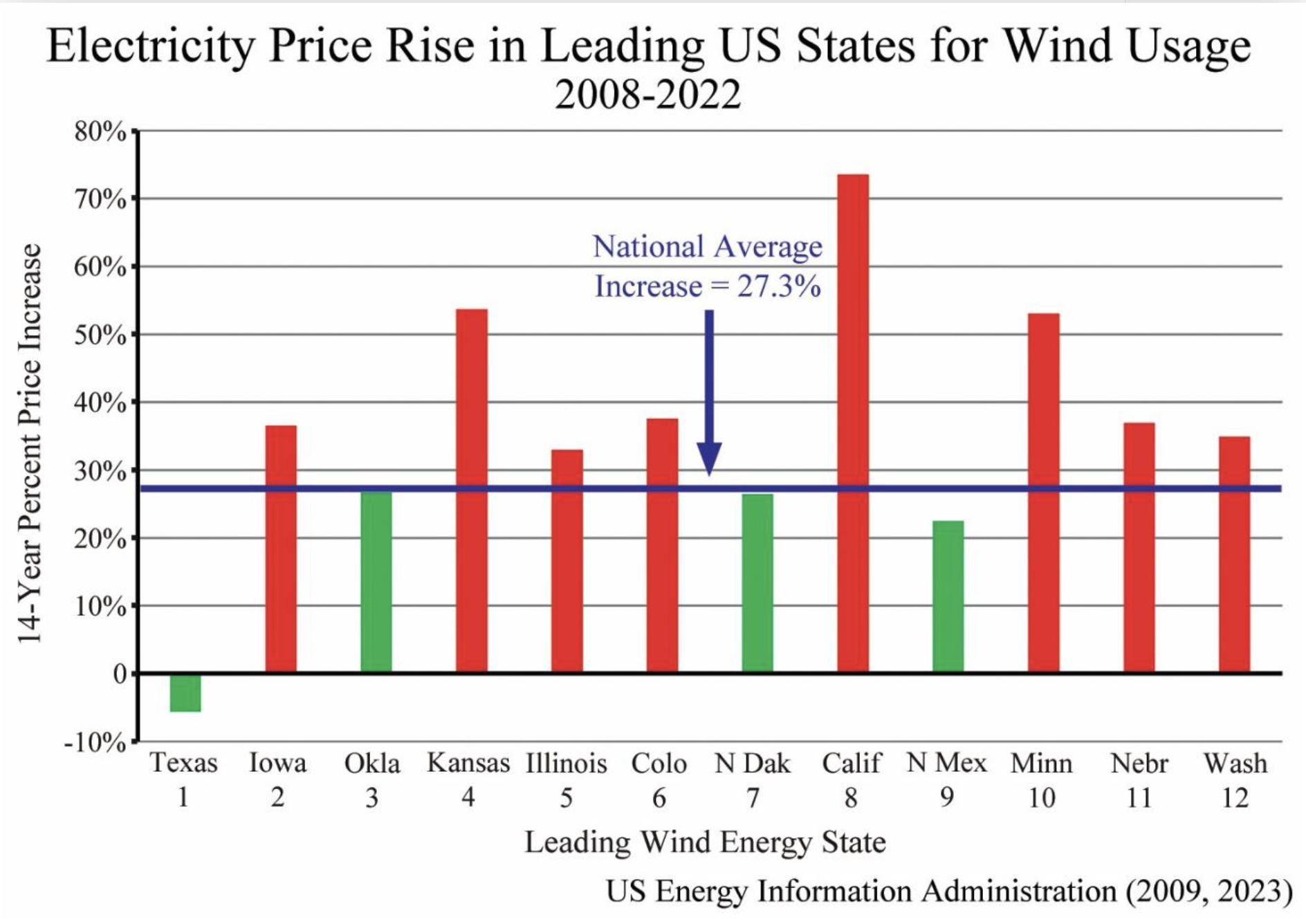

Electricity prices in states with the highest penetration of wind systems are rising faster than the national average.

US average electricity prices rose 27 per cent from 2008 to 2022. But in eight of the top 12 wind states, power prices rose between 33 and 73 per cent over the 14-year period. Prices rose in Iowa (36%), Kansas (54%), Illinois (33%), Colorado (37%), California (73%), Minnesota (53%), Nebraska (37%), and Washington (35%), which are the number 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 12 leading states in terms of electricity generated from wind, respectively. Price increases were lower than average in Texas, Oklahoma, North Dakota, and New Mexico, the other four leading wind states. The data shows that deployments of wind systems produce higher electricity prices.

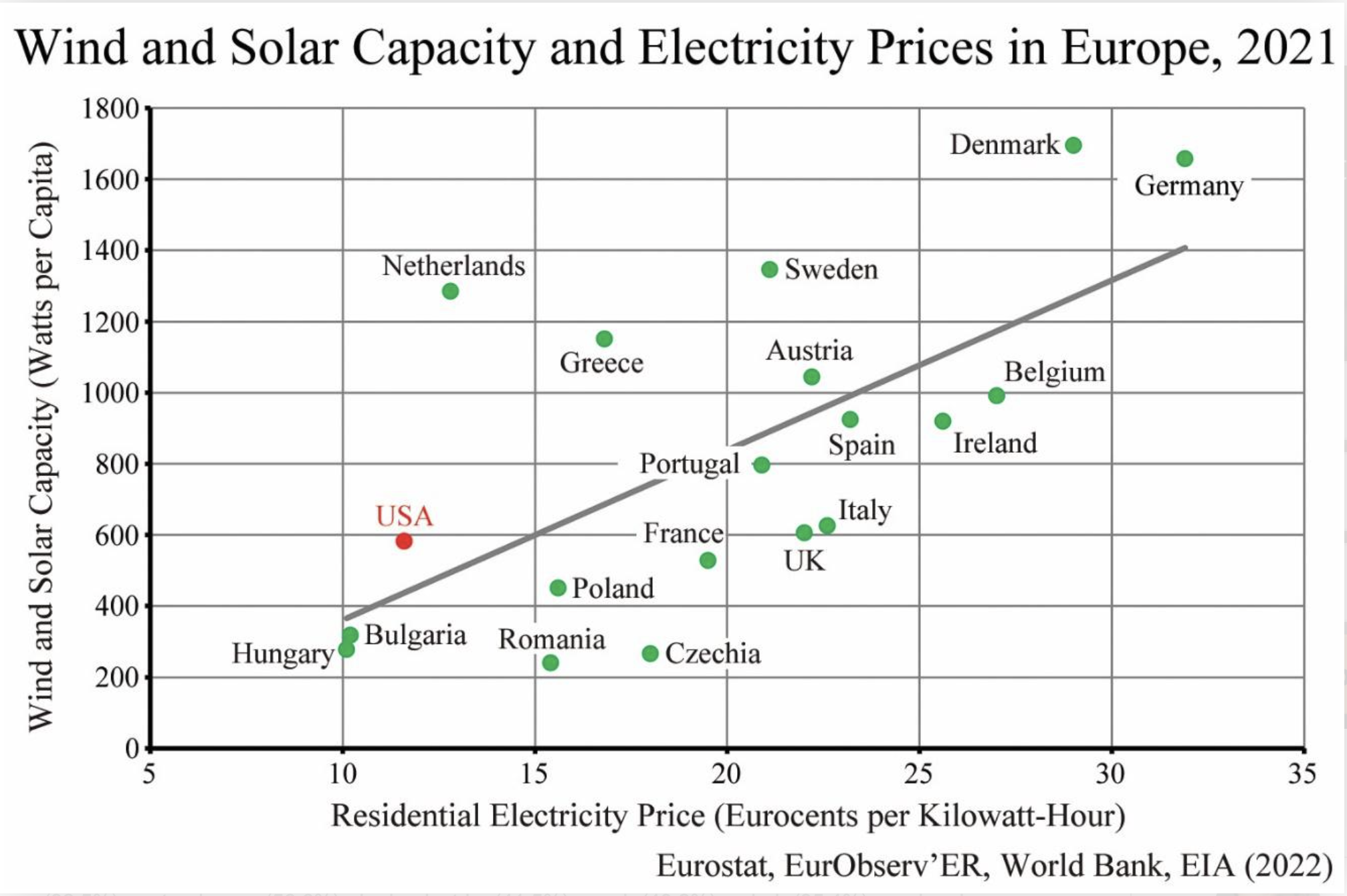

In Europe, the nations with the most wind and solar capacity deployed, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Spain, and Sweden, experience the highest residential electricity prices.

Residents of Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Romania, where few renewables are deployed, pay half as much per kilowatt-hour as the leading renewable countries. Denmark and Germany have deployed over 1,600 watts per person of wind and solar, the highest density in Europe. Electricity prices for Denmark (29 eurocents per kilowatt-hour) and Germany (32 eurocents/kW-hr) are the highest in Europe, and two and one-half times the prices in the US, where renewable penetration remains lower. In Europe, like the US, wind (and solar) deployments raise electricity prices.

Wind systems increase electricity prices in three ways. First, wind intermittency raises power prices. Wind system electricity output can vary between full-rated output to near zero within a period of only a few hours. Wind systems typically produce between 25 per cent and 40 per cent of rated output. In 2020, US power plant utilization levels were nuclear (92.5%), natural gas (56.6%), hydroelectric (41.5%), coal (40.2%), wind (35.4%), and solar photovoltaic (24.9%).

The intermittency of wind and solar means that, if always-on electricity is to be supplied, reliable coal, natural gas, and nuclear generators must be maintained as wind and solar systems are added to the power grid. Power system operators know that up to 90 per cent of the capacity of traditional generators must remain operational to prevent system blackouts. Therefore, addition of renewables boosts both the capacity and the number of needed systems, raising the cost of electricity.

Second, backup coal and natural gas systems must be run at lower utilization rates as operators push for higher percentages of renewable output. The low utilization levels for coal and natural gas systems in 2020 mentioned above are because these systems are scaled back in favour of wind and solar output. Backup systems are not able to operate profitably at low utilization levels, raising system costs and electricity prices.

Third, wind (and solar) systems require more and longer transmission power lines than traditional power plants. Coal, gas, and nuclear plants are located near population centres and tend to be large-capacity plants. These plants can be connected to the grid with relatively short, high-capacity transmission lines. Wind systems tend to be located in remote areas, such as on ridgelines, often far from cities. Wind and solar are spread out over wide areas and require 100 times the land of traditional plants. Longer transmission systems over wide areas need to be deployed for wind and solar, raising system costs and electricity prices.

As more wind systems are added to the power grid, residents should prepare for soaring electricity prices.

Originally published at WND