Table of Contents

Julian Spencer-Churchill

Dr. Julian Spencer-Churchill is associate professor of international relations at Concordia University, and author of Militarization and War (2007) and of Strategic Nuclear Sharing (2014).

It is now a truism that political leaders don’t initiate wars with the expectation that they will be protracted contests of attrition. It is an interesting counter-factual conjecture whether Russian President Vladimir Putin, if he had a crystal ball two or three years into the war in Ukraine, would have still started his war, even without evidence of his defeat.

John Mearsheimer, in his 1984 Conventional Deterrence, has a slew of case studies where failed blitzkrieg offensives transformed themselves into intractable slogs. US journalist William L Shirer reported that Hitler knew of his short war-long war gamble, as he had warned his military staffers that if the ensuing war became protracted, Germany could only hold out for a few years.

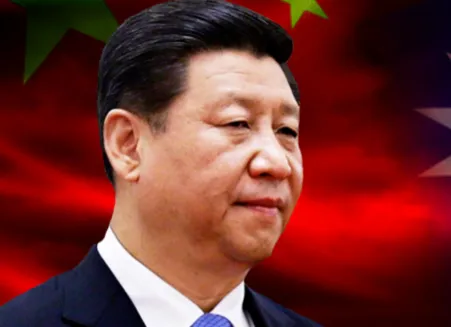

The same consideration applies to Chinese Communist General Secretary Xi Jinping’s conception of the time horizon to complete an invasion of Taiwan. Short wars are of course rational, as a fait accompli would pre-empt any response by a slow-mobilizing US alliance. However, if the lightning attack fails, then Putin and Xi would risk becoming victims of regime change by the extent of the re-organization they would need to impose on their citizens and industry in order to strengthen their respective countries.

The widespread expectations of a short war at the beginning of the 20th century were reasonable given the experience of the destructive firepower of the new rifles and heavy artillery during the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War, and the rationality that no political leader should want to pay the cost of another generationally long French revolution cum Napoleonic struggle (1792–1815). Most of the major power conflicts in 19th-century Europe, with the notable exception of the Crimean War, were concluded within just a few months, primarily for diplomatic reasons. It was also widely believed that the high rate of munitions expenditure in a conventional conflict between NATO and the Warsaw Pact in Europe would have quickly led to a stalemate, negotiations, or use of nuclear weapons. All of the 1965 and 1971 Indo-Pakistan Wars, and the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, were terminated in part due to the unexpectedly high rate of munitions expenditure, especially of artillery rounds.

A small minority of observers, such as Jewish-Polish financier Jan Bloch, and, British Secretary of State Herbert Kitchener, shared a more realistic appraisal of the political impossibility of a short war. Bloch, in his 1898 Future of War, saw that industrialized economies could, and by political dynamics, would be compelled to sustain the mobilization of millions of soldiers through to exhaustion. Kitchener’s pessimism of the first world war was based on his experience of the protracted 1899–1902 Second Boer War. Reagan administration defense official, Fred Charles Ikle, in his 1971 Every War Must End, showed that wars become lengthened because of the empowerment of less compromising governmental officials making greater promises to an increasingly vengeful public as casualties mount.

German author Fritz Sternberg, in his 1938 Germany and a Lightning War (also the book to first mention Blitzkrieg), was one of the few authors to predict in detail the shortcomings of Hitler’s war plan espoused in his 1925 Mein Kampf. Sternberg believed that the scale of USSR’s geography and its matching manufacturing made a quick Nazi victory, or even an eventual triumph, impossible. As an example of the detail of his analysis, Sternberg suggested that Hitler was likely aware that Stalingrad contained a quarter of the USSR’s weapons manufacturing capacity, and was a gateway to Baku, which provided the USSR 80 per cent of its oil, and that therefore it would be a major military objective.

Hungarian professor Ivan Lajos, in his 1939 Germany’s War Chances, confirms Sternberg, adding that Soviet industry was 500 km behind its frontiers, and had a higher output than Germany’s. Both Sternberg and Lajos noted that in German military journals as early as 1936, staff planners discounted the likelihood of a short war or of a miracle weapon to achieve victory, noting the attritional nature of war between industrial powers. Erich von Ludendorff made a similar attritional argument in his 1936 The Total War.

Long wars also risk the loss of allies and the provocation into being of new adversaries. Sternberg argued that Italy would likely abandon Germany, for a second time, given Rome’s economic weakness. For Lajos, even a small risk of alienating the US should have been obvious to Hitler, given that US industrial production outweighed the totals of Germany, Great Britain and France combined. The US manufactured more automobiles than the rest of the world and extracted two-thirds of all of the world’s oil, advantages that were especially decisive in winning the type of armored warfare Germany was embarking on. In fact, Germany’s automobile industry was even behind France.

Sternberg further emphasized that regardless of the inconvenience caused by the Japanese and Italian fleets to commercial lanes, the undefeatable Anglo-US fleets had such a reach that they could ship war materiel from their manufacturing bases to the littoral of any ally on the globe, ultimately defeating their adversaries. Shirer noted that General Thomas, head of the Economic and Armaments Branch of OKW, reported to Commander of the German armed forces under Hitler, Wilhelm Keitel, that Germany lacked the resources and food to fight an Anglo-French coalition that would inevitably result from an invasion of Poland.

Like the first world war, and unlike the second world war, the economic and energy balance between the US and its allies versus the China-Russia axis and its allies is far more even, and therefore likely to produce a protracted attrition war, punctuated by the use of nuclear weapons as one side begins to lose.

2024 World Bank data shows that China accounts for 31.6 per cent of the world’s manufacturing capacity, as compared with 15.9 per cent for the US, and 22 per cent for major US allies in the top ten (Japan, Germany, India, South Korea, Italy, Mexico, and France).

Both South Korea and Indonesia manufacture more than Russia (2.7 and 1.81 versus 1.8 per cent), and Mexico out-produces Frances (1.7 to 1.6 per cent). Brazil has a larger manufacturing base than the UK, Turkey more than Spain, and Iran more than Sweden.

Although China produced far more cars (27 million) than the US (10m), a better surrogate for armored vehicle output is 2022 commercial vehicle manufacturing: U.S. (8.3m), China (3.2m), Morocco (2.9m), Thailand (1.3m) Japan (1.3m), and India (1m).

The US and its NATO allies still account for over 95 per cent of total global aircraft production by valuation, which is a good proxy for technical sophistication. However, by gross tonnage of merchant vessels in 2023, China accounts for 33M, South Korea by 18m, Japan by 10m, and the rest of world by just 4m, which is worrying. The US ranks just ahead of Iran and behind Indonesia, Turkey, Netherlands, and Russia. Most unsettling is that the US ($5.9bn) ranks behind China (27.1bn) in value of machine tools, even if including all of its major state allies (Italy, Germany, Japan, South Korea and India [21.2bn]).

Sternberg was remarkably accurate in his predictions of Hitler’s plans, his reckless diplomacy, and the fact that despite the prevalence of armored warfare, that it was attrition by industrial capacity that would determine victory. However, Sternberg’s aversion to Nazism and his consequent isolation from German sentiment, meant that his predictions of a revolt against Hitler among the soldiers, workers, farmers, middle and factory-owning classes, was not only false, but failed to appreciate the resilience of the Nazi state, and the modern state in general. This is a serious issue for those seeking victory in Ukraine by the overthrow by coup of Russian President Vladimir Putin, or avoiding war over Taiwan by threatening to conjure the same coup threat against the Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping.

Predicting how protracted wars end, like the Russo-Ukraine War, or whether China could seize Taiwan and survive the ensuing naval blockade, what damage North Korea could inflict on its neighbor, and how Iran could seize and if it can be expelled from the Straits of Hormuz, is a very complex technical issue best handled by fine-grained wargaming.

The implications of the short-war illusion is that deterrence by the democracies must always be primed for a demonstration of its capability and credibility. Allegations of long-term planning by Putin and Xi are really just a jumble of short and episodic domestic political maneuvers to stay in power, and Western deterrence must be visible enough to be incorporated into those calculations. The democracies must not pattern the traditional Western complacent practice of allowing the enemy to conduct a surprise attack in order to mobilize its domestic population, like the 1940 Fall of France or the 1941 strike on Pearl Harbor.

During the Cold War, NATO was faced with the dreaded choice of triggering a tactical nuclear war either at the commencement of hostilities along the East German border before most of NATO’s divisions were overrun, or in a last-ditch desperate defense on the Rhine, and it was this uncertainty that held the USSR at bay.

Concurrently, given China’s overwhelming manufacturing capability, which may be sustained by Russia’s energy supplies in the event of a US naval blockade of China’s Middle Eastern oil, requires that NATO must also demonstrate that it has a plan for a protracted years-long conflict. Nuclear deterrence must also be robust enough in the event that imminent failure leads to considerations of a desperate nuclear attack by the Kremlin or Beijing.

One important strategy, given the increasing shift of manufacturing to the developing world, is to cultivate allies by the difficult mission of creating new liberal democracies.

This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.