Table of Contents

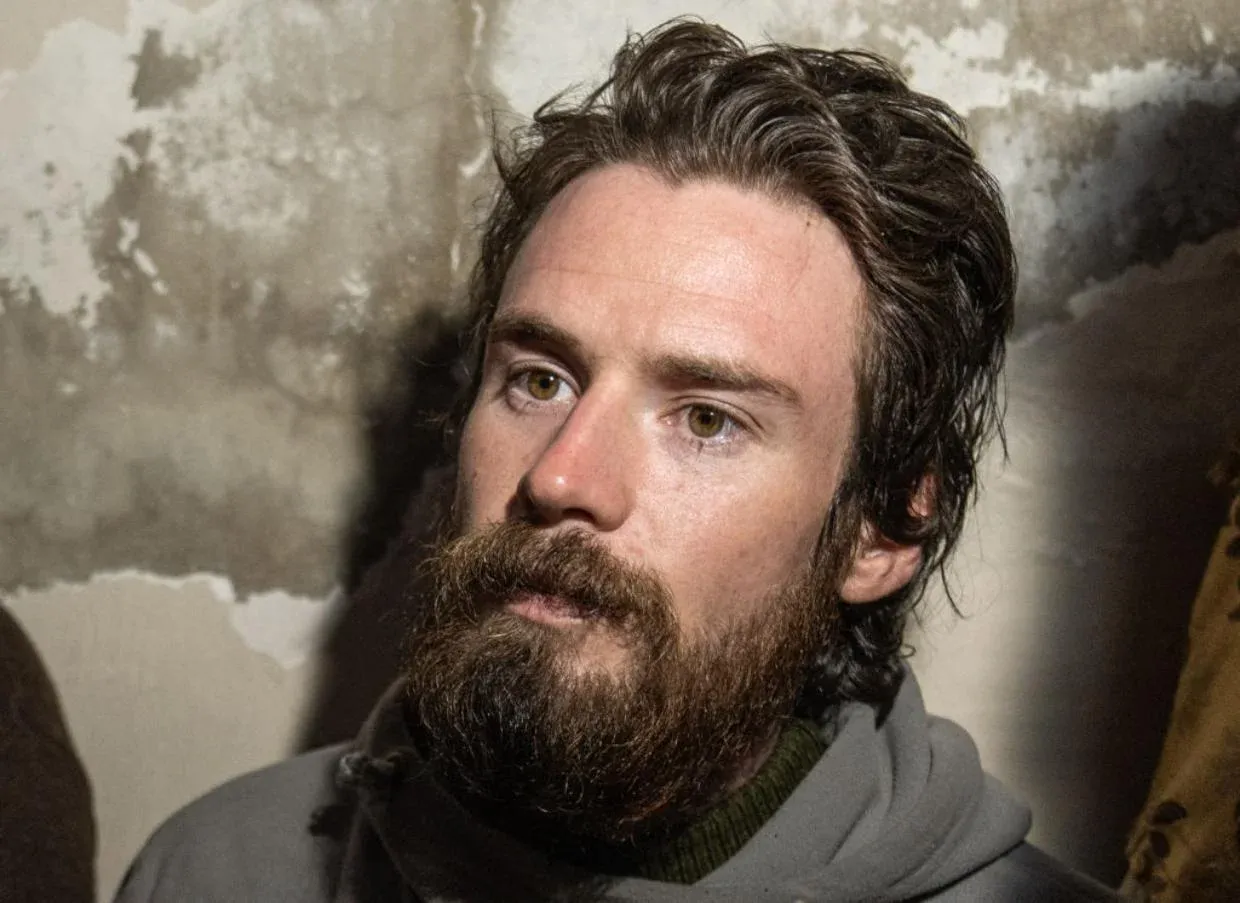

Bruce W. Davidson

Bruce Davidson is professor of humanities at Hokusei Gakuen University in Sapporo, Japan.

After three full years of public masking, Japanese government officials recently declared that people are now allowed to uncover their faces, if they so wish. An international school teacher I know told me that this news prompted her Japanese student to exclaim, “This is the happiest day of my life!” Probably that is an indication of how unhappy the masking has made many children.

In many respects, official policies in regard to Covid impoverished people’s lives. Here I am mostly leaving aside conspicuous, concrete harms, such as the devastating economic damage caused by the lockdowns and the harmful health impact of Covid-related measures. This article will focus on other significant damages to the quality of life in Japan.

I write about these things with no animosity toward Japanese people. In fact, I find Japan attractive in many respects, some of which I explained in a written tribute to modern Japan some years ago. In particular, I very much admire the civility, common expressions of gratitude, and respect for tradition among Japanese people. I would much rather live here than anywhere else. Sadly, some of these qualities are diminishing as a result of the continuing Covid panic. Moreover, negative aspects of Japanese society, once in retreat or relatively benign, are now being exacerbated.

Germ Phobia: Though they are finally free not to wear masks, only a minority are actually availing themselves of this freedom. Most of those still masked have apparently become germaphobes, though some use masks for their allergies or other reasons.

Devotion to hygiene in Japan has often been commendable. Public restrooms here may be the best in the world, and Japan pioneered and developed modern toilets. However, the sometimes obsessive desire to eliminate all dirt and germ contamination leads to extremes of behaviour at times. For example, when they take baths, some people vigorously scrub their skin, which leads to inflammation and skin problems. Furthermore, all the bathing results in a significant number of bath-related accidents and deaths. Around 19,000 bathtub deaths occur in Japan each year.

Now Covid germ-paranoia has led to heightened anxiety about human contact. In addition to masking, people entering buildings and restaurants were directed to disinfect their hands with alcohol. At some hospitals, patients are still interrogated by a nurse before being allowed to enter. Maintenance staff have been continually wiping down all surfaces with alcohol. One doctor in Sapporo changed her clinic location to accommodate patients afraid to ride buses. A former student of mine, a healthy young woman in her twenties, quit her job because she feared having contact with customers. Her case is not at all unusual. Japan is rapidly becoming a nation of Howard Hugheses.

Rude, Inconsiderate Behaviour: The germ phobia led to rude behaviour even in a country famous for civility and politeness. Another cause of this is Covid groupthink, which motivates bullying and rudeness. For example, recently buses and subways have had a “no talking” rule, since talking supposedly spreads Covid. I once observed a bus driver get up from his seat, walk to the back of the bus, and loudly scold a group of chattering high school students. They were not in a classroom; they were riding a bus.

Many hotels, shopping centres, parks, and other places severely restricted or completely removed benches and chairs during the height of the panic. This was certainly a hardship for the handicapped and the elderly. It is quite possible that some suffered heart attacks or other problems from being unable to find a place to sit down when they were weary.

Xenophobia: Somehow Covid became associated with foreigners, despite the fact that the spread of Covid in Japan was well underway at least from the days of the Diamond Princess cruise ship outbreak in February, 2020. At the end of 2021, the Japanese government tried to stop all flights from abroad until the plan prompted a backlash from Japanese people who would have been stranded abroad just before the New Year’s holidays. For several years foreign visitors were not allowed into Japan without irksome, lengthy quarantine requirements.

Ugliness: Japan maintains its reputation as a country with a fine sense of aesthetics. In its architecture, art, and fashions, Japan has excelled, and that has been a very significant aspect of the attraction of Japan. At graduations and other events, Japanese women often wear beautiful kimonos and have their hair specially adorned. However, the Covid religion demands the veiling of the face. Covering much of their faces with masks certainly dampens the aesthetic appeal of those wearing kimonos. In such ways Covid panic has made Japan a less visually attractive place.

Poor Communication: Communication between people can sometimes be difficult in Japan. Japanese often do not explicitly state requests or desires but instead rely on subtle, indirect hints, facial expressions, and gestures to get messages across. This process has been rendered much more difficult by masks and reliance on online meetings. People are much harder to read when their voices are muffled behind masks and their expressions are largely hidden. For children, who are still developing, these communication difficulties are much greater.

Child Abuse: Generally speaking, Japanese people do not abuse children and even show a conspicuous love for children and childhood. Children are often doted on and spoiled —from a traditional Western point of view. My own children were lavished with gifts, money, and attention from friends, neighbours, and total strangers in Japan. For Girls’ Day in March, someone once dressed my little daughter in a kimono and took her photo. One child of mine came home one day with a big jar of candy from an unknown adult at a local playground.

So it is very sad to see such people masking children and forcing on them the dangerous, experimental Covid injections, of which they have no need and which may cause their deaths. Moreover, as is the case elsewhere, children in Japan have been getting the message that they are a threat to the lives of their grandparents. One Okinawa artist created a children’s picture-book to allay such fears, titled (by my loose translation) “Even Without a Mask, You’re a Good Kid.” Along with explaining some health harms of masks, the book also provides data about the kinds of suffering schoolchildren have been experiencing as a consequence of masking, such as bullying by teachers and fellow students.

In January, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida gave a speech expressing worry about Japan’s low birth rate and declining population. However, the Covid panic fostered by government officials and others has probably only compounded this problem. People afraid of human contact and unable to communicate well will likely be discouraged from dating, marrying, and child-bearing. There is no national future in the cultivation of a fearful population.