Table of Contents

EKO

Artist and bookmaker

Recently, the Pentagon cut ties with Harvard. The debate is about politics and funding.

Harvard has older debts than that.

Every documentary starts with the cabin. Every podcast starts with the manifesto. Every true crime book starts with the brother who made the phone call.

Nobody starts in the room on Divinity Avenue.

In the fall of 1959, a 17-year-old boy sat in a chair in a room with a one-way mirror.

Someone taped electrodes to his chest. Three sensors for heart rate. Two on the fingertips for galvanic skin response. A band around his rib cage for respiration.

The week before, they’d asked him to write an essay. The instructions were specific:

Describe your most personal beliefs.Your deepest values.What you think the purpose of human life is.

He wrote about mathematics. About the beauty of logical systems. About nature. The order in the physical world and how it can be apprehended by a mind working alone.

He handed in the essay believing it was a personality assessment.

It was a weapon. They gave it to a law student with a folder and a psychological battle plan.

The law student sat down across from the boy. Opened the folder. Read for a moment. Then looked up.

The next 22 minutes were designed to destroy the boy’s beliefs, his values, and his sense of self. Using his own words as the tools.

The law student read the boy’s phrases back to him, reframed as evidence of pathology.

You wrote about nature because you have nothing else. You eat alone in a dining hall full of people who will run this country. That’s not a philosophy. It’s the diagnosis of a person who can’t get anyone to eat dinner with him.

The sensors recorded everything.

Heart rate up 30 beats. Galvanic skin response at levels the researchers later noted as “consistent with acute psychological distress.”

The boy said four words total.

Behind the glass, a 16mm camera captured the whole thing. And behind the camera sat the man who designed the protocol.

His name was Henry Alexander Murray.

Sixty-six years old. Groton. Harvard. Columbia Medical School.

During the war, Murray served as the chief personality assessment officer for the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime predecessor to the CIA. His job at the OSS was to design methods for evaluating how human beings break under sustained psychological pressure.

What their failure mode looks like.

He brought those methods home to Harvard.

The funding came from the Department of Defense and the Rockefeller Foundation. The study recruited 22 bright, gifted undergraduates. Each one wrote personal essays. Each one sat in the chair. Each one was filmed while a trained adversary took their beliefs apart. Each one was then forced to watch the footage of their own humiliation.

More than 200 hours across three years.

Murray called it “stressful interpersonal disputation.”

The boy was the youngest subject in the study. Enrolled at Harvard at 16. Turned 17 before his first session. His personality, his sense of who he was and what he believed, was still under construction when Murray’s protocol began disassembling it.

He signed a consent form. Nobody reads the fine print at 17.

He was assigned a code name.

The code name was LAWFUL.

When the program was discontinued in 1962, Harvard sealed the records. The data, the consent forms, the researcher’s notes, the 16mm films – all of it locked in a university vault.

Many of the 22 subjects reported lasting effects. A nihilism that arrived one day and never left. An anger that lives in the body and surfaces before the mind can name it. An inability to trust the act of speaking honestly to another person.

The boy with the code name LAWFUL graduated from Harvard the same year the program ended. He was 20 now. His professors described his mind as extraordinary. A mathematical instrument capable of work most of them couldn’t follow.

PhD at Michigan. Won the Sumner Myers Prize. Berkeley hired him at an age no one in their department’s history had matched.

Then he quit. Two words: I quit.

He moved back to his parents’ house. Worked odd jobs at a factory. Then he and his brother bought a small parcel of land outside a town called Lincoln, Montana. One point four acres. Lodgepole pine. A creek.

He built a cabin. Ten feet by 12. An axe from a surplus store. A handsaw from the hardware store. A stove from salvaged sheet metal.

No electricity. No running water. No telephone.

He lived there for 25 years.

During those years, he hunted rabbits and grew potatoes and hauled water in buckets and walked the ridgelines in the long summer evenings. He also filled 40,000 pages of coded journals.

He also built bombs.

Between 1978 and 1995, he killed three people and injured 23. He mailed explosive devices to universities and airlines. He typed a 35,000-word manifesto on a manual typewriter by candlelight – no electricity – arguing that modern technological society destroys human freedom and dignity.

That the system processes people.

That the only response is to destroy the system.

The Washington Post published it in September 1995. His sister-in-law, a philosophy professor, recognized the voice immediately. She’d read it before. In letters her brother-in-law had been sending for years.

Same cadence. Same compression.

Same airtight sentences that left no room for another person’s thought.

His brother called the FBI. The FBI promised confidentiality and no death penalty.

They honored neither condition.

April 3, 1996. Two FBI agents and a forest service officer walked up the path to the cabin dressed like neighbors. Flannel and jeans. He opened the door.

Inside, the FBI inventoried everything. The journals. The bomb-making materials. A completed device, packaged and addressed, ready to mail.

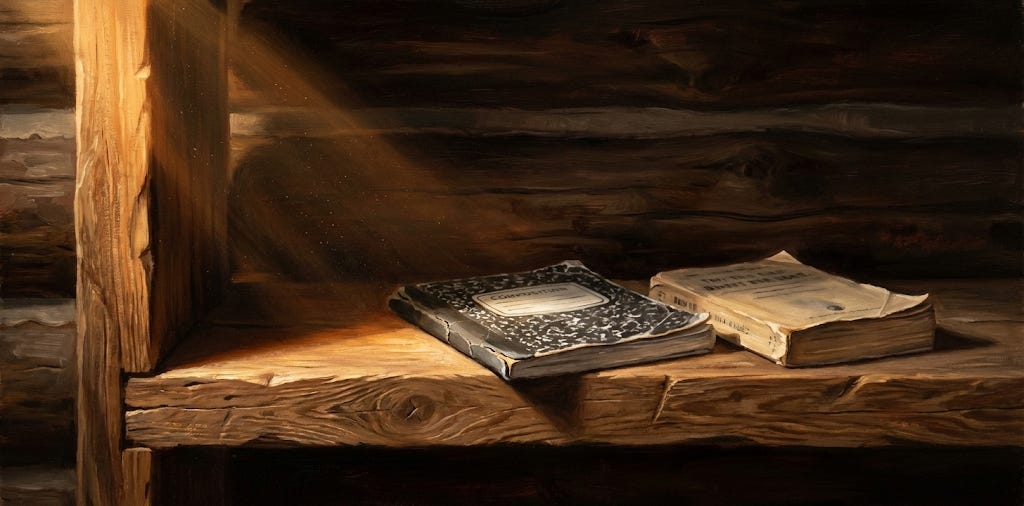

And on the shelf, next to a copy of Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, Murray’s protocol. Studies of Stressful Interpersonal Disputation.

The manual of the experiment.

He had carried it for 34 years. From Harvard to Michigan to Berkeley to his parents’ house to a 10-by-12 cabin in the Montana wilderness.

At trial, his lawyers wanted to argue insanity. He refused.

His logic was airtight, the way it had always been airtight.

If I am mentally ill, the manifesto is a symptom. If I am sane, it is an argument. You are asking me to destroy my own argument to save my own life.

The judge wouldn’t let him represent himself. He couldn’t argue the ideas. He took the plea deal. Four life sentences plus 30 years.

At sentencing, the victims spoke. A woman whose husband lost three fingers threw his own journal entry back at him. You described the results of that experiment as “adequate but no more than adequate.”

Another woman, whose husband was killed by a package next to the Christmas tree: My children are bleeding from their souls.

He read a six-sentence statement from a piece of paper. He did not say he was sorry. He did not look at the victims.

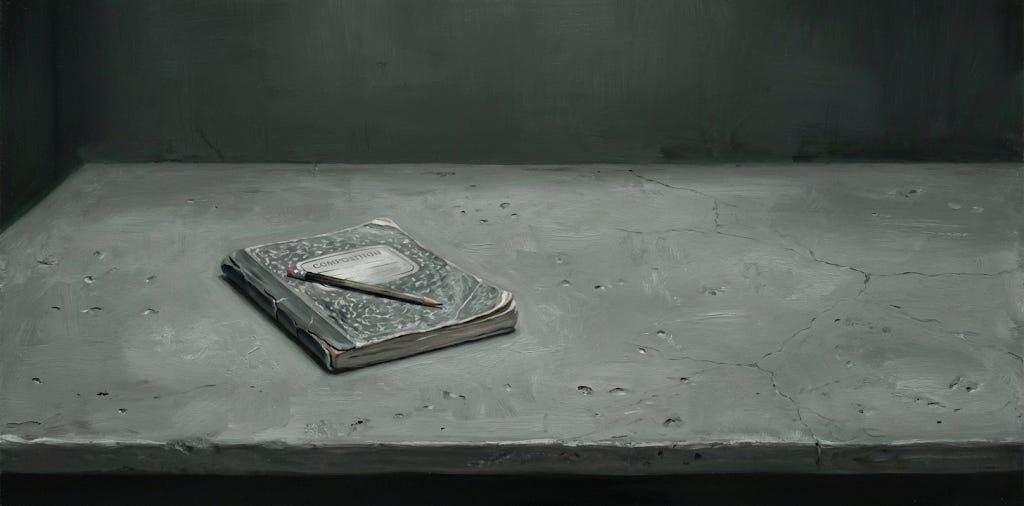

ADX Florence. Seven by 12. A concrete bed. A four-inch window facing a wall. Twenty-two hours a day in the cell.

He wrote. He had always written. He would always write.

His brother wrote to him every year. He never answered once.

On June 10, 2023, Theodore John Kaczynski was found dead in his cell at a federal medical facility in Butner, North Carolina.

Suicide. Eighty-one years old.

On the desk? A notebook.

The last in a series that stretched back 65 years, from a suitcase carried through Johnston Gate to a concrete desk in a federal prison.

Harvard locked the Murray experiment records in a vault in 2000.

They’ve never been opened. No one at the university has been held accountable. No one at the CIA has acknowledged the connection between Murray’s work and the agency’s behavioral research programs.

The experiment ended. The subject was discarded. The files disappeared.

Now our government is cutting ties with Harvard. Good. But the conversation is about funding and ideology. Nobody is asking about the experiments.

The question isn’t about one man in one cabin. It’s about what happens when institutions, the ones with the money and the mirrors and the consent forms nobody reads, put their hands on a child and never take them off.

The room is still there.

Draw your own conclusions.

I wrote a book about this.

If you hate reading on screens, print it out.

The paperback lands on Amazon this Friday.

This article was originally published by EKO Loves You.