Table of Contents

Eliran Arazi

PhD researcher in Anthropology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (Paris).

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The discovery and rescue of four young Indigenous children, 40 days after the aircraft they were travelling in crashed in the remote Colombian rainforest, was hailed in the international press as a “miracle in the jungle”. But as an anthropologist who has spent more than a year living among the Andoque people in the region, conducting ethnographic fieldwork, I cannot simply label this as a miraculous event.

At least, not a miracle in the conventional sense of the word. Rather, the survival and discovery of these children can be attributed to the profound knowledge of the intricate forest and the adaptive skills passed down through generations by Indigenous people.

During the search for the children, I was in contact with Raquel Andoque, an elder maloquera (owner of a ceremonial longhouse), the sister of the children’s great-grandmother. She repeatedly expressed her unwavering belief the children would be found alive, citing the autonomy, astuteness and physical resilience of children in the region.

Even before starting elementary school, children in this area accompany their parents and elder relatives in various activities such as gardening, fishing, navigating rivers, hunting and gathering honey and wild fruits. In this way the children acquire practical skills and knowledge, such as those demonstrated by Lesly, Soleiny, Tien and Cristin during their 40-day ordeal.

Indigenous children typically learn from an early age how to open paths through dense vegetation, how to tell edible from non-edible fruits. They know how to find potable water, build rain shelters and set animal traps. They can identify animal footprints and scents – and avoid predators such as jaguars and snakes lurking in the woods.

Amazonian children typically lack access to the sort of commercialised toys and games that children in the cities grow up with. So they become adept tree climbers and engage in play that teaches them about adult tools made from natural materials, such as oars or axes. This nurtures their understanding of physical activities and helps them learn which plants serve specific purposes.

Activities that most Western children would be shielded from – handling, skinning and butchering game animals, for example – provide invaluable zoology lessons and arguably foster emotional resilience.

Survival skills

When they accompany their parents and relatives on excursions in the jungle, Indigenous children learn how to navigate a forest’s dense vegetation by following the location of the sun in the sky.

Since the large rivers in most parts of the Amazon flow in a direction opposite to that of the sun, people can orient themselves towards those main rivers.

The trail of footprints and objects left by the four children revealed their general progression towards the Apaporis River, where they may have hoped to be spotted.

The children would also have learned from their parents and elders about edible plants and flowers – where they can be found. And also the interrelationship between plants, so that where a certain tree is, you can find mushrooms, or small animals that can be trapped and eaten.

Stories, songs and myths

Knowledge embedded in mythic stories passed down by parents and grandparents is another invaluable resource for navigating the forest. These stories depict animals as fully sentient beings, engaging in seduction, mischief, providing sustenance, or even saving each other’s lives.

While these episodes may seem incomprehensible to non-Indigenous audiences, they actually encapsulate the intricate interrelations among the forest’s countless non-human inhabitants. Indigenous knowledge focuses on the interrelationships between humans, plants and animals and how they can come together to preserve the environment and prevent irreversible ecological harm.

This sophisticated knowledge has been developed over millennia during which Indigenous people not only adapted to their forest territories but actively shaped them. It is deeply ingrained knowledge that local indigenous people are taught from early childhood so that it becomes second nature to them.

It has become part of the culture of cultivating and harvesting crops, something infants and children are introduced to, as well as knowledge of all sort of different food sources and types of bush meat.

Looking after each other

One of the aspects of this “miraculous” story that people in the West have marvelled over is how, after the death of the children’s mother, the 13-year-old Lesly managed to take care of her younger siblings, including Cristin, who was only 11 months old at the time the aircraft went down.

But in Indigenous families, elder sisters are expected to act as surrogate mothers to their younger relatives from an early age. Iris Andoke Macuna, a distant relative of the family, told me:

To some whites [non-Indigenous people], it seems like a bad thing that we take our children to work in the garden, and that we let girls carry their brothers and take care of them. But for us, it’s a good thing, our children are independent, this is why Lesly could take care of her brothers during all this time. It toughened her, and she learned what her brothers need.

The spiritual side

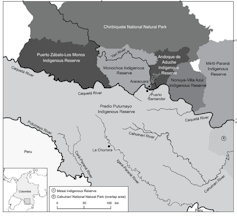

For 40 days and nights, while the four children were lost, elders and shamans performed rituals based on traditional beliefs that involve human relationships with entities known as dueños (owners) in Spanish and by various names in native languages (such as i’bo ño?e, meaning “persons of there” in Andoque).

These owners are believed to be the protective spirits of the plants and animals that live in the forests. Children are introduced to these powerful owners in name-giving ceremonies, which ensure that these spirits recognise and acknowledge relationship to the territory and their entitlement to prosper on it.

During the search for the missing children, elders conducted dialogues and negotiations with these entities in their ceremonial houses (malocas) throughout the Middle Caquetá and in other Indigenous communities that consider the crash site part of their ancestral territory. Raquel explained to me:

The shamans communicate with the sacred sites. They offer coca and tobacco to the spirits and say: “Take this and give me my grandchildren back. They are mine, not yours.”

These beliefs and practices hold significant meaning for my friends in the Middle Caquetá, who firmly attribute the children’s survival to these spiritual processes rather than the technological means employed by the Colombian army rescue teams.

It may be challenging for non-Indigenous people to embrace these traditional ideas. But these beliefs would have instilled in the children the faith and emotional fortitude crucial for persevering in the struggle for survival. And it would have encouraged the Indigenous people searching for them not to give up hope.

The children knew that their fate did not lie in dying in the forest, and that their grandparents and shamans would move heaven and earth to bring them back home alive.

Regrettably, this traditional knowledge that has enabled Indigenous people to not only survive but thrive in the Amazon for millennia is under threat. Increasing land encroachment for agribusiness, mining, and illicit activities as well as state neglect and interventions without Indigenous consent have left these peoples vulnerable.

It is jeopardising the very foundations of life where this knowledge is embedded, the territories that serve as its bedrock, and the people themselves who preserve, develop, and transmit this knowledge.

Preserving this invaluable knowledge and the skills that bring miracles to life is imperative. We must not allow them to wither away.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.