Table of Contents

Giada Ferrucci

Western University

Giada ferrucci is a Ph.D. Candidate in Media Studies at Western University. She holds a BA in Economic Development and International Cooperation from the University of Florence, Italy, where her research focused on the opium trade in Afghanistan and alternative economic development reforms, and an MA in International Relations from Aarhus University in Denmark, where I focused on the human right to water.

After more than 20 years of conflict in Afghanistan, the withdrawal of United States-led forces is causing a humanitarian crisis as the Taliban takes control of the country.

Heroin, morphine, opium, hashish and poppy have mostly benefited the Taliban in recent years, and that likely means destitute Afghans will be dependent on the opium trade for survival.

Afghanistan’s opium boom began in the 1980s as drug traffickers capitalized on the chaos following the invasion by the Soviet Union in 1979.

But Gen. Tommy Franks, who co-ordinated the invasion of Afghanistan by American ground troops, declared in 2002: “We are not a drug task force. This is not our mission.” That was a message to the opium lords not to side with the Taliban because the U.S. had no intention of interfering with production.

Ever since, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has analyzed and monitored Afghan opiates.

The Taliban are drug traffickers as much as they are self-described Islamist militiamen. Following the preaching of the Quran, the Taliban are ostensibly opposed to the consumption and cultivation of drugs. But in her book Seeds of Terror: How Heroin Is Bankrolling the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, author Gretchen Peters explains that the Taliban’s 2001 ban on poppy cultivation was merely tactical. “Afghanistan cannot survive without opium. It is simultaneously killing Afghanistan while also keeping a huge number of people alive,” she has said.

A Taliban Ploy?

In his first news conference, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid pleaded for “international assistance” to provide farmers with alternative crops to poppies. But NATO, nongovernmental organizations and the U.N. have not succeeded in breaking Afghanistan’s reliance on poppy farming.

Mujahid promised that the new government would not turn Afghanistan into a narco-state. Yet these pledges seem simply a ploy by new Taliban leaders to look more moderate. Mujahid has not yet explained how the Islamist group will ban opium, a key resource for them.

In the meantime, the Taliban realize that promising to ban heroin could secure international support, according to Jonathan Goodhand, an expert in international drug trade at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London.

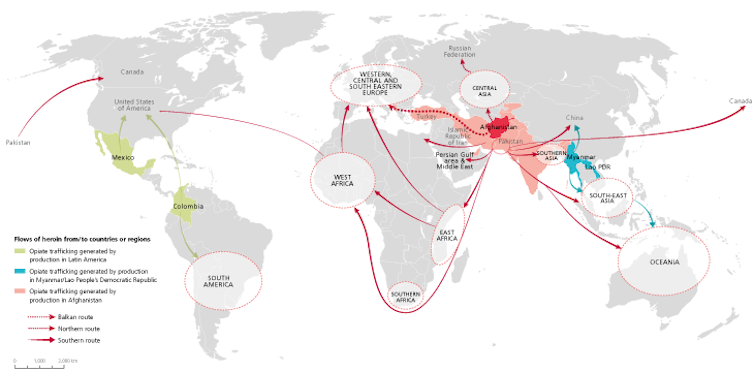

Most likely, Afghanistan will remain a huge illicit opiate supplier, producing more than 90 per cent of the world’s heroin. Controlling the country will also offer the Taliban access to airlines, the state bureaucracy and banks, facilitating the opium trade and money-laundering.

As the Taliban, warlords and corrupt public officials vie for drug profits and power, it will fuel even more instability in the country.

The Reach, Impact of Taliban Heroin

Taliban heroin supplies the Camorra, ‘Ndrangheta and Cosa Nostra drug cartels in Italy, the Russian cartels and most distribution organizations in the U.S.

Recently, traffickers have also discovered that ephedra, a plant commonly found in Afghanistan, can create a crucial component of methamphetamine, also known as “crystal meth.”

Drug addiction in Afghanistan is an ignored but growing epidemic. As the COVID-19 pandemic raged in 2020, poppy cultivation increased by 37 per cent.

Legitimate pharmaceutical companies also buy opium from licensed producers who increasingly buy from Indian companies that source directly from Afghanistan. That means the Taliban plays a role in determining what painkillers, anesthetics and psychiatric drugs are used around the world.

Drug Trafficking, Poverty Link

Opium currently makes up six to 11 per cent of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product. The drug has an impact on governance and economic development leading to insurgency, terrorism, corruption and poor health. The structural drivers of the illicit Afghan drug economy — insecurity, political struggle and a lack of economic alternatives — will likely worsen under the Taliban.

The link between drug trafficking and poverty is the complex byproduct of lack of economic opportunities, access to justice and corruption levels. Bribery, theft and tax evasion are the norm when dealing with the judiciary and police. Yet any attempt to crack down on the opium trade hurts the farmers, not the Taliban.

So how to proceed?

Similarly, efforts to eliminate opium poppy as a crop should remain suspended until peace has been achieved. In the past, airstrikes on suspected heroin labs and efforts to eliminate the crop have stoked anger against the national government in Kabul that implemented these initiatives and its foreign backers.

While initiatives to provide alternative livelihoods to Afghans should support the country’s rural economy, there’s also a need for infrastructure investment and private sector development, as well as improved access to treatments for Afghan drug addicts.

Finally, ensuring human and women’s rights are protected must be a priority for the international community. Its efforts should also target traffickers and drug lords while demanding an adherence to the rule of law. As the country’s former president, Hamid Karzai, said in 2005: “Either Afghanistan destroys opium, or opium will destroy Afghanistan.”

Giada Ferrucci, PhD Candidate, Media Studies, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD.