Table of Contents

It’s a common claim of porch atheists that ‘Hur, hur, Jesus never existed.’ They claim that there’s no evidence of his existence – which is an obvious lie. The evidence may be scant, but it is all the more remarkable that it even exists.

It’s hard for modern minds, saturated with television, radio, newspapers and internet, but for most of human history, the lives of most people went almost completely unrecorded. In Britain, for example, it wasn’t until the 16th century that the crown ordered the keeping of parish records of births, deaths and marriages. The General Register Office wasn’t established until the 1830s.

For millennia, almost the only births, deaths and marriages regularly recorded were those of the elites: nobility, or other prominent people such as generals, priests, scholars and scribes. Certainly the birth and death of a lower-middle-class carpenter in a far-flung province of the Roman empire would have passed without notice – unless he did something extraordinary.

As historian Geoffrey Blainey says, the very fact that we know anything at all about Jesus is remarkable in itself. But what do we know, and how?

Virtually all of the supposed physical evidence, the scattering of ‘relics’, can be discounted. Like the Shroud of Turin, they’re fakes. To paraphrase Martin Luther, Jesus was nailed with three or four nails – and 30 of them are in reliquaries in Europe alone.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are one of the most important discoveries in Biblical archaeology – not least because they were contemporaneous with Jesus’ life.

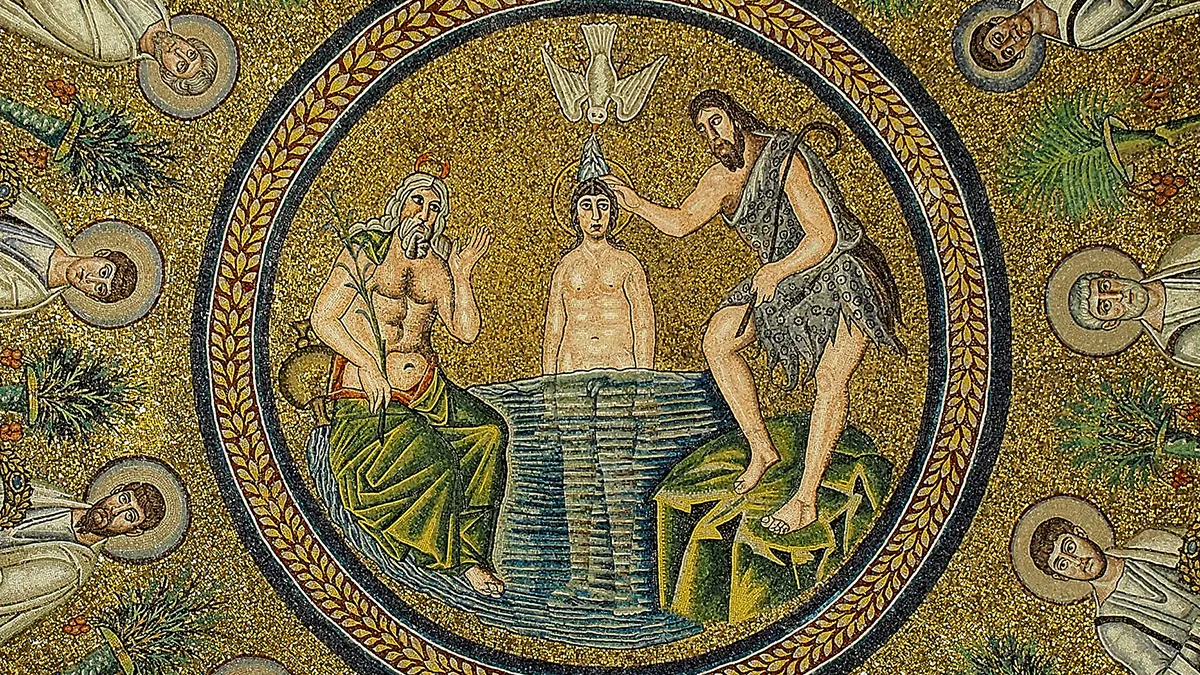

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a vast trove of parchment and papyrus documents found in a cave in Israel in the 1940s, were written sometime between 150 BC and AD 70. In one place, the scrolls refer to a “teacher of righteousness”. Some say that teacher is Jesus. Others argue that he could be anyone.

But the Dead Sea Scrolls are far from the only textual evidence for Jesus’ existence. Roman historians like Suetonius, writing around a century after Jesus’ death, refers to the Christ cult by name. Which is at least proof that a group following the teachings of Jesus quickly gained prominence.

Another historian, born around the time of Jesus’ death, and writing some 30 years later, was the Roman-Jewish Flavius Josephus. A Jewish soldier who first fought against the Romans in Galilee, then joined them, Josephus would naturally be expected to be hostile to what, to him, would have been an heretical cult. Josephus describes such important Christian events and people as Quirinius’ census, Pilate, John the Baptist – and the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James.

Josephus remains one of the earliest literary references to Jesus’ existence – outside of the Bible itself.

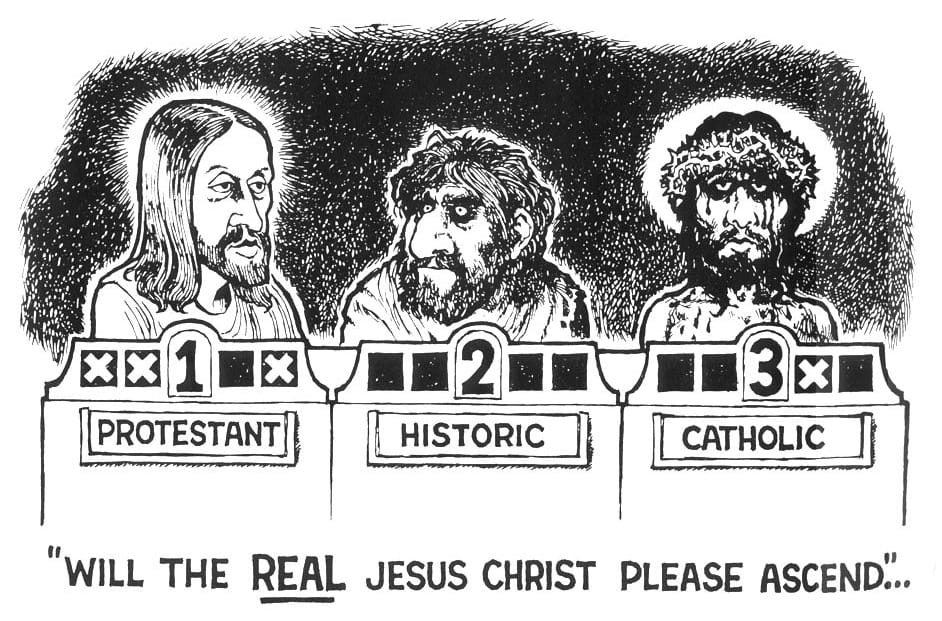

The Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are thought by scholars to have been written by four of Christ’s disciples in the decades after his crucifixion. There are still other Gospels, never canonized but written by near-contemporaries of Jesus all the same. Many details differ between the various accounts of his life and death, but there’s also a great deal of overlap, and through centuries of careful analysis biblical scholars have arrived at a general profile of Jesus, the man.

Several of the gospels bear similarities that led scholars to conclude that they drew from a now-lost document, dubbed “Q” (from the German Quelle, or ‘source’). This document, then, would hypothetically have been written within just years of Jesus’ life, drawing on oral tales, or the memories of survivors who were Jesus’ contemporaries.

“We do know some things about the historical Jesus – less than some Christians think, but more than some skeptics think,” said Marcus Borg, a preeminent Biblical scholar, author and retired professor of religion and culture at Oregon State University. “Though a few books have recently argued that Jesus never existed, the evidence that he did is persuasive to the vast majority of scholars, whether Christian or non-Christian.”

LiveScience

Even if “Q” never existed, the very fact that within just 30 years – living memory, in other words – the life and death of an obscure religious teacher in distant Roman backwater in the first century was thought notable enough to record is a remarkable fact in itself. As Blainey says, “By the standard of the times, his life is astonishingly documented. He did not become well known until the last years of his life, and then only in one small outpost of the Roman Empire.”

And yet, within just a few years, people were recording the teachings and the fact of the existence of this ‘Boy from Galilee’.