Table of Contents

Republished with Permission

Author: Bryce Edwards

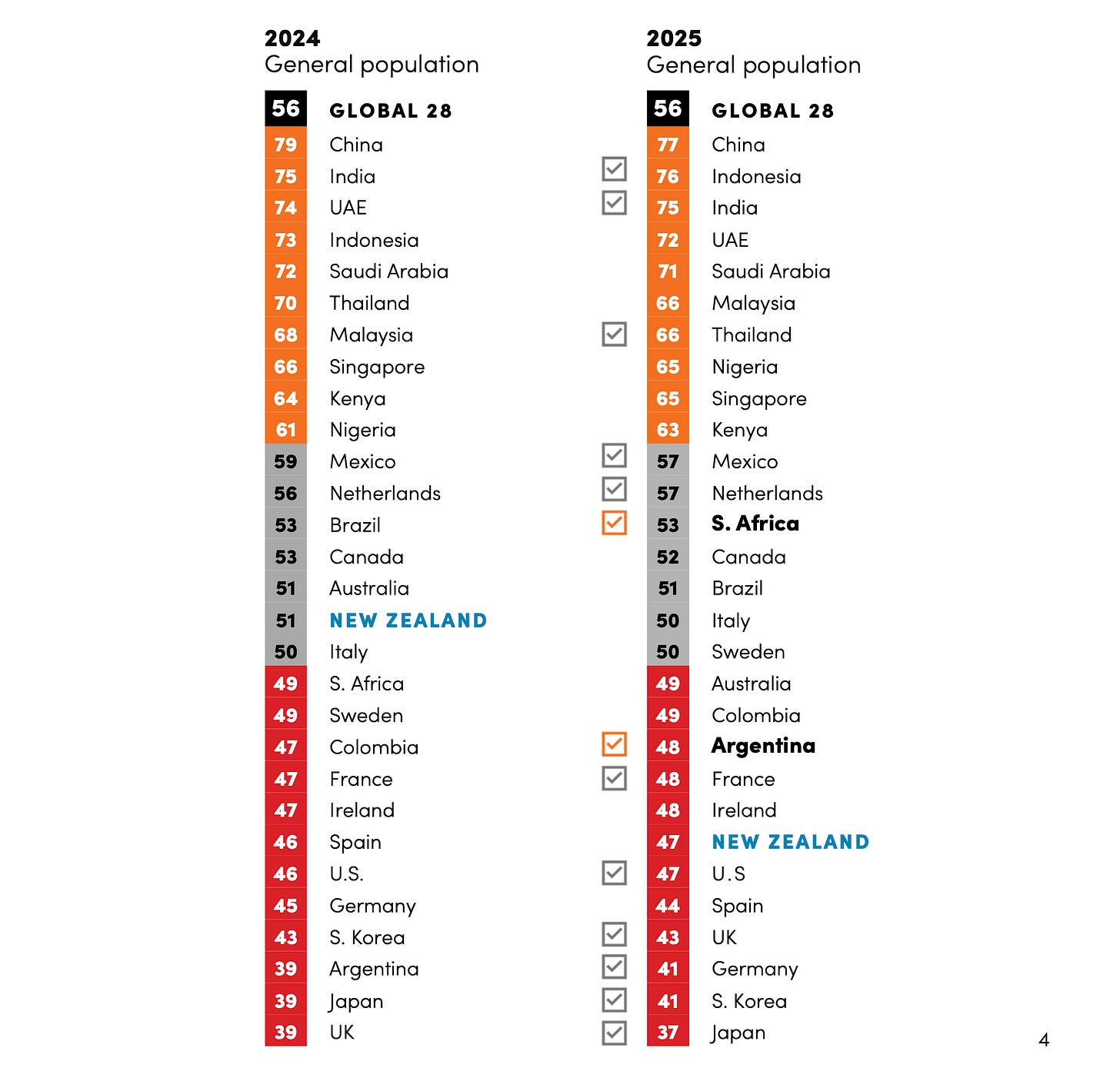

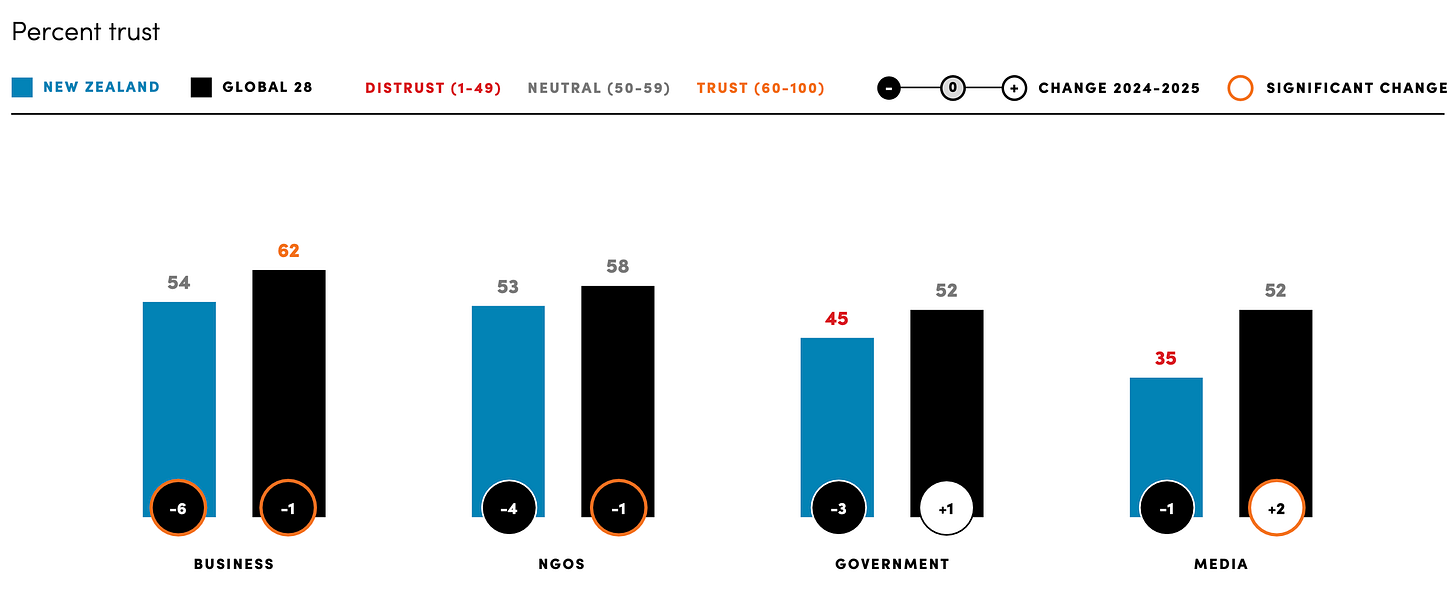

New Zealand is in the throes of a trust crisis. The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer – an annual global survey of confidence in institutions – delivers a stark warning: public faith in the country’s core pillars of society has plummeted. Trust in government is down to 45%, business sits at 54%, and trust in media has collapsed to a mere 35%.

These results were released on Friday, and they are in line with other results that show New Zealanders are increasingly discontented with the status quo, and especially unhappy with the role that the rich are playing in politics and society. You can see the report here: The Acumen Edelman Trust Barometer shows a sense of grievance

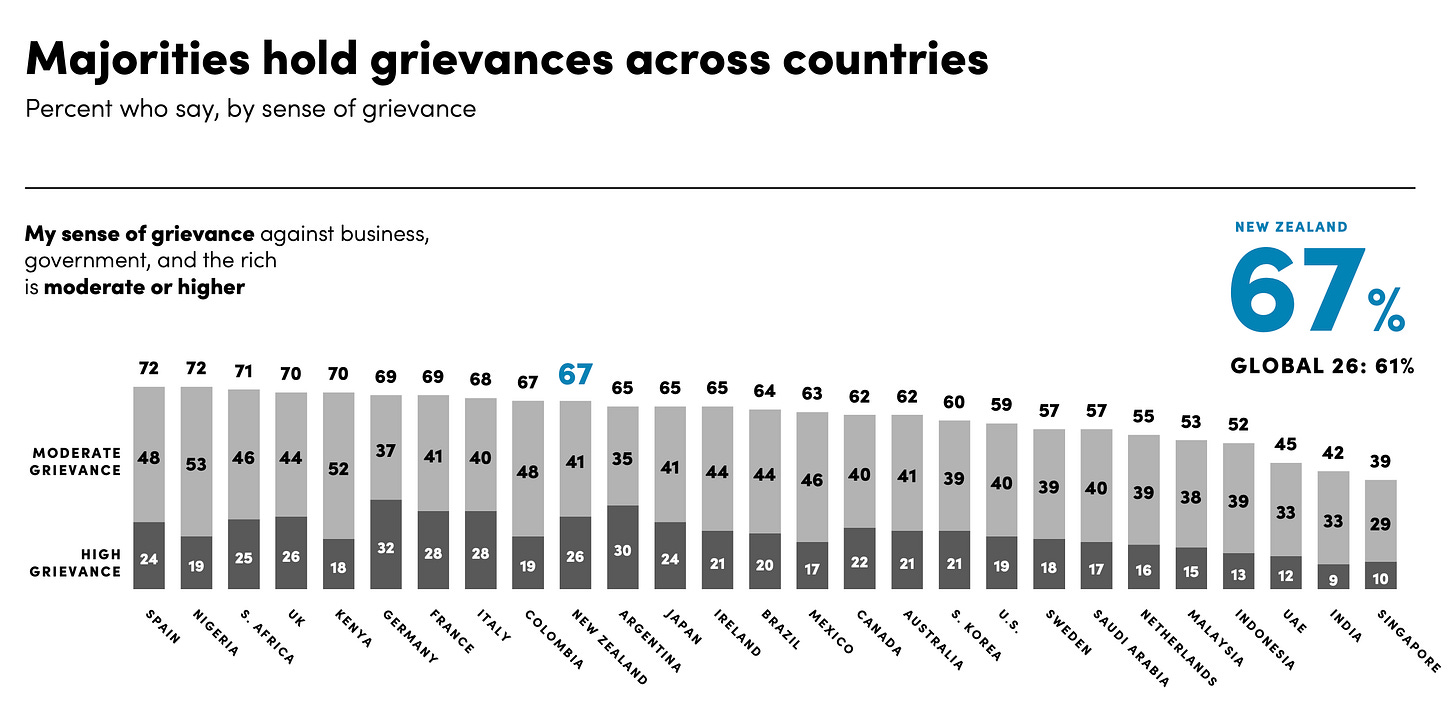

For the first time in the 25 years of the Edelman Trust Barometer being published, New Zealand’s overall trust index has fallen into outright distrust territory – dropping to 47%, below the global average of 56%. Perhaps most telling, a full 67% of New Zealanders report moderate to high levels of grievance toward institutions, believing that government, business and “the wealthy” actively disadvantage ordinary people. Such findings point to a country “divided by mistrust,” where scepticism has deepened into a pervasive sense that the system is rigged in favour of an elite few.

These trends mirror a broader pattern of democratic malaise. Economic anxieties and systemic unfairness have metastasized into what Edelman calls a “Crisis of Grievance,” both in New Zealand and abroad. Adelle Keely, chief executive of the firm’s NZ partner, notes New Zealanders feel “overlooked by those in power and disillusioned as a result”. Business in particular is on a downward trajectory, with a significant 6-point drop in trust over the past year. Keely warns the 2025 results “should be a major wake-up call to all leaders”, as Kiwis demand far more from institutions that are seen to be failing them.

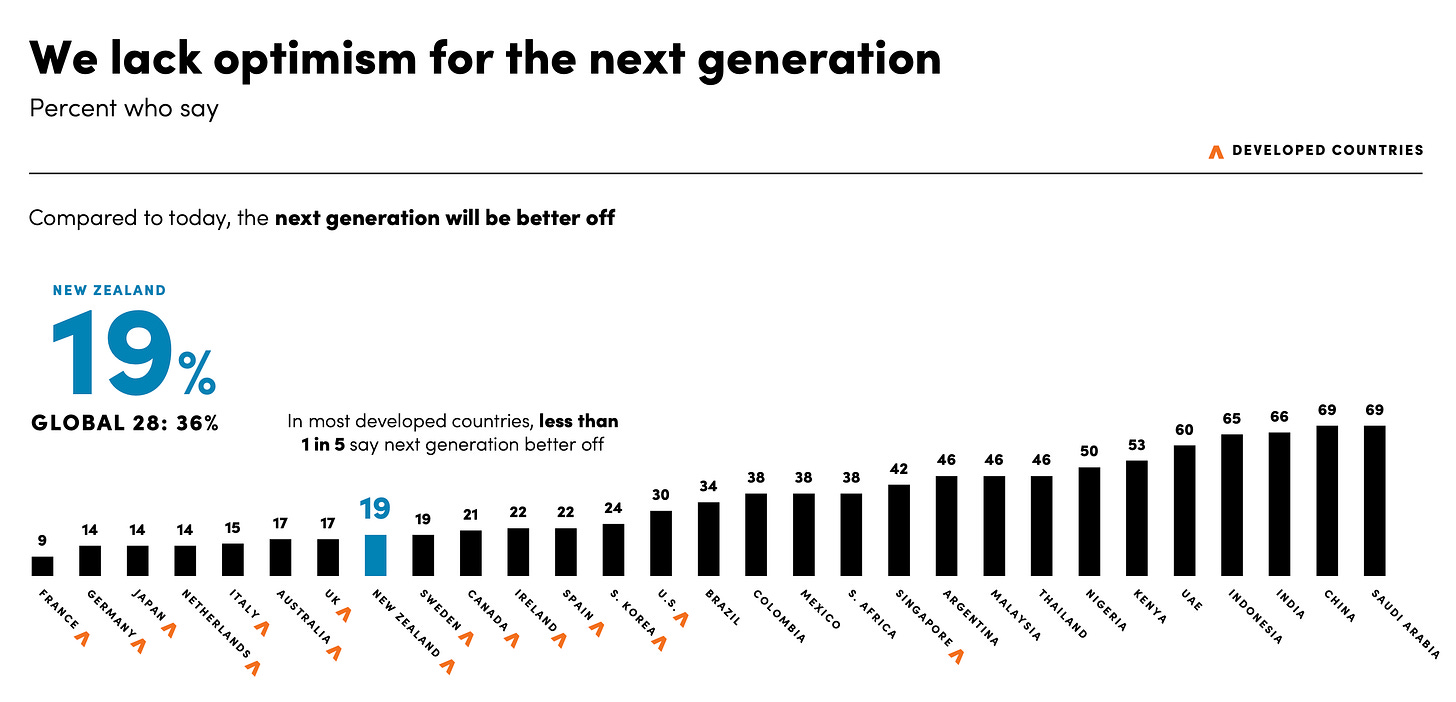

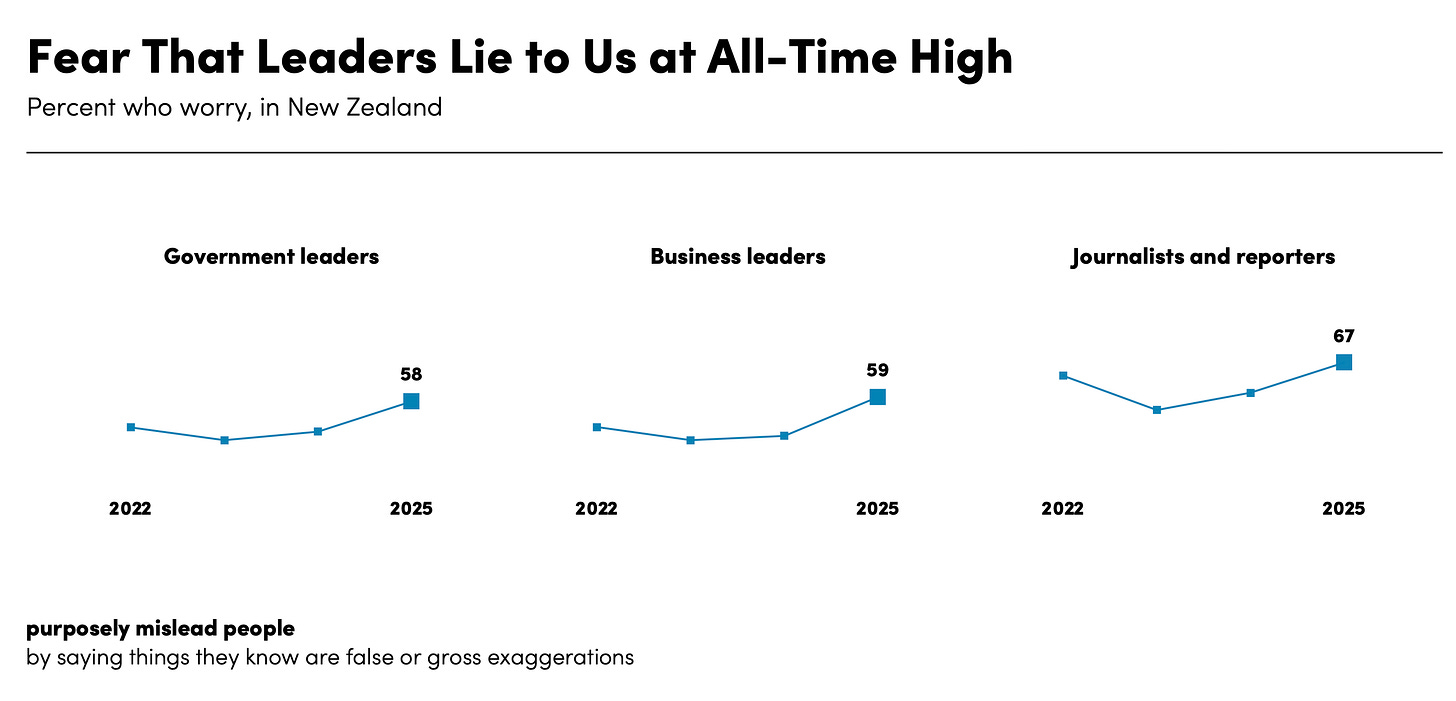

Three psychosocial factors accompany the wave of grievance, she says: a lack of hope for the next generation, a lack of trust in leaders, and a worry that leaders are wilfully lying to the public. Indeed, the data shows only 19% of New Zealanders believe today’s youth will be better off in the future (versus 36% globally), and 61% worry that officials and business leaders are purposely misleading the public. A striking 68% also feel it’s becoming harder to tell whether news comes from reputable sources or those trying to deceive. In short, Kiwis are losing confidence not just in what leaders say, but in the very integrity of the institutions those leaders represent.

A Long time coming: Trust erodes amid inequality

While the Edelman Barometer shines a spotlight on 2025, New Zealand’s discontent has deeper roots. Other recent surveys echo these findings and give historical context. Political scientists Jack Vowles and Mona Krewel of Victoria University have observed that public dissatisfaction in New Zealand tends to spike whenever governments are seen as too cozy with wealthy business interests. Over recent decades, however, New Zealand had paradoxically been one of the few developed nations to experience some long-term growth in trust – building off its traditions of egalitarianism and good governance. This makes the current freefall in confidence all the more alarming, though perhaps not yet irreversible.

The warning signs have been accumulating: by the 2023 election, voter turnout was notably low and cynicism high. As I noted at the time of 2023 election, many citizens had simply “turned off” from the uninspiring campaign – surveys showed voters were not very enamoured by any would-be prime minister, and parties were failing to inspire people with solutions to the country’s problems. I explained then that mainstream politicians weren’t sufficiently addressing the big issues that worry New Zealanders – be it housing affordability, cost of living, or inequality – causing many to tune out of the political process in disgust.

Beneath this political disengagement lies a widening chasm of economic and social inequality. New Zealand perceives itself as a land of fair play, but public opinion suggests many see that ideal slipping away. A 2024 Ipsos poll found nearly two-thirds (65%) of New Zealanders believe the economy is “rigged to advantage the rich and powerful.” Only a scant 17% disagreed with that statement. Similarly, 63% agreed that “the political and economic elite don’t care about hard-working people,” and 55% felt that traditional politicians “don’t care about people like me.”

Similarly, a new report to be released this week by the Helen Clark Foundation has some similar survey evidence. Reporting on this in the Herald today, Jamie Morton writes: “Only 42% of respondents believed the Government acted in people’s best interests most or all of the time” – see: Australians happier, less divided than New Zealanders – Helen Clark Foundation report (paywalled)

Such views point to a collapse in institutional legitimacy: a majority feel shut out and ignored by both government and business elites. It’s notable that these figures are almost identical to global averages in the Ipsos “Populism” survey – New Zealanders are no outliers in their cynicism, but part of a worldwide wave of frustration.

Public anger is also fed by visible inequities. In the latest Edelman poll, Kiwis overwhelmingly agree that wealthy people are not paying their fair share of tax – a sentiment reinforced by an official Inland Revenue study showing the country’s 311 richest individuals often pay effective tax rates less than half that of ordinary workers. Stories of a booming wealthy elite – profiting from soaring property prices, stock market gains, and generous tax loopholes – alongside statistics that one in five children lives in poverty paint a stark picture. As has been frequently noted, New Zealand’s wealth gap has been widening, with 70% of wealth held by the top 20% of households.

The Edelman data also underscore this sense of unfairness: New Zealanders score higher than average on the belief that the “system” is stacked against them. The common thread is a demand for fairness and accountability: most New Zealanders believe the status quo favours an entrenched elite, and they want that to change.

Grievance politics or a democratic reawakening?

As trust in institutions declines, New Zealand’s public discourse is splitting in two directions. On one side are calls to address the “crisis of grievance” head on – to treat rising public discontent and distrust as a rational response to real problems, and to channel it into positive change. On the other side are attempts to downplay or divert the discontent, sometimes by blaming it on misinformation or by dismissing public anger as misplaced. Business columnist Roger Partridge, who chairs the New Zealand Initiative – a group representing big business – warns that an excessive focus on grievance can become “grievance politics” – a blame game that polarises society without solving anything.

Writing for the NZ Herald on Friday, Partridge argues that instead of fixating on what divides (for example, finger-pointing at “the rich”), New Zealand must “find common ground” – see: Beyond grievance politics: New Zealand’s search for common ground (paywalled)

He urges a pivot back to practical solutions on issues like housing, education and productivity – areas where tangible policy action could improve people’s lives and, presumably, rebuild trust. In his view, indulging in anger toward elites or other groups risks entrenching cynicism and getting us nowhere. Some commentators have indeed tried to wave away the Edelman findings, chalking up public frustration to either reflexive tall-poppy resentment of “the rich” or to bigoted scapegoating of minorities. But such glib explanations ignore the genuine structural causes driving disillusionment.

Those structural issues are hard to deny. Critics note that wealthy interests wield significant behind-the-scenes influence in New Zealand’s politics – influence that is often opaque to the public. As I’ve documented before, the lobbying industry is entirely unregulated, operating with very little transparency or oversight. This lack of rules means corporate lobbyists and ex-politicians-turned-fixers can exert pressure on policy without the public ever knowing.

Compounding the issue, political donations remain large and sometimes hidden, with weak disclosure rules enabling corporations, trusts or wealthy individuals to pour money into party coffers semi-anonymously. New Zealand, once proud of its clean governance, has thus grown vulnerable to government capture and undue influence, eroding the average citizen’s voice. When big money speaks louder than voters, it’s no wonder people begin to see an emerging oligarchy at odds with democratic ideals. With such vulnerabilities, economic inequality has grown and voter participation has decreased. In this light, public grievance starts to look less like petty envy or ignorance and more like a legitimate alarm sounding about the state of our democracy.

Not all consequences of collapsing trust are constructive, however. According to the Edelman survey, significant numbers now condone spreading disinformation, threats, or even violence as legitimate tools for change, which is a sign of how deeply alienated some have become. The new report says that about one in eight New Zealanders (12%) believe violence (or threats of it) is a viable way to achieve societal change. The challenge, then, is preventing righteous grievance from mutating into destructive cynicism. The silver lining in today’s discontent is that people are wide awake to issues of inequality and unaccountable power. The risk for leaders in New Zealand is that if they don’t respond, this energy could curdle into something more dangerous.

A Global wave of distrust and anger

This phenomenon is not unique to New Zealand – it’s part of a broader crisis shaking numerous democracies. Many Western democracies now cluster at the bottom of the trust rankings, reflecting widespread cynicism. Australia, the United States, the UK, France, Germany, and Japan all register low overall trust (scores under 50) in business, government, media and NGOs.

In the United States, the land of the American Dream, distrust in institutions has reached profound levels – especially among the young. A Gallup global poll highlighted by the Financial Times this month shows that less than one-third of Americans under 30 trust their own government, one of the worst rates in the developed world. By some measures, young Americans’ confidence in government is at a record low, rivalling levels seen in countries like Greece and Italy that have faced severe crises. Such disillusionment reflects not only recent political turmoil but decades of growing inequality and stalled social mobility. It’s telling that many Americans now feel they have lost personal agency – a record 31% of young people in the US say they lack freedom to control their lives, a sobering statistic for a country that prides itself on liberty.

In the UK too, trust has plummeted after years of Brexit acrimony, pandemic struggles, and economic stagnation. Britain’s Trust Index sits in the low 40s, and public discourse frequently returns to the theme that a privileged few are reaping rewards while others bear the sacrifices. The Edelman Trust Barometer globally found that six in ten respondents across 28 countries feel a moderate to high sense of grievance, agreeing that “the system is deliberately stacked against regular people.” From South Africa to France to Japan, people are voicing versions of the same complaint: our leaders have failed us, and we no longer trust them.

This global zeitgeist has given rise to a new class of political figures and movements who openly challenge “the oligarchy” and vow to restore power to the people. Few voices embody this more than Bernie Sanders in the United States. The veteran senator has spent years railing against the “billionaire class” and warning that the US is “moving rapidly into an oligarchic form of society”. Dismissed as an outlier a decade ago, Sanders’ message now resonates with huge crowds. He points to facts like the wealth of a few dozen billionaires eclipsing that of the bottom half of society, or the flood of big money into elections, as evidence that democracy is being subverted by plutocracy. “We can’t go around the world saying, ‘Oh, Putin has an oligarchy.’ Well, we’ve got our oligarchy here too,” Sanders quips, in reference to America’s own power elite. In a recent interview during his nationwide “Fight Oligarchy” tour, Sanders put it bluntly: “You’ve gotta be kind of blind not to understand that you have a government of the billionaire class, for the billionaire class, by the billionaire class.”

His rhetoric taps into a palpable anger that spans partisan lines – an anger at Wall Street, at tech moguls, at politicians in hock to donors. It’s no coincidence that similar language is heard in the UK from figures like Jeremy Corbyn (with his slogan of “for the many, not the few”) and even from moderate centrists decrying “the elite” when scandals erupt.

The sentiment is not about left or right in ideology; it’s about bottom vs top in the social hierarchy. And the Edelman data suggest that this bottom-up frustration has reached a boiling point in many countries. Even Establishment insiders are acknowledging it: Richard Edelman himself, the PR mogul behind the Trust Barometer, told the Davos elite this year that public trust is “plummeting” and the world faces a “descent into grievance” unless leaders change course. When a professional advisor to business and government sounds such an alarm, it’s a sign that popular discontent can no longer be ignored by those in power.

Restoring trust: Rebuilding democracy from the ground up

New Zealand’s surge of public discontent may feel destabilising, but it also carries the seeds of democratic renewal. In the past, periods of crisis and low trust have often precipitated positive reforms. The Progressive era in the early 20th century, for instance, was born out of disgust at America’s Gilded Age oligarchs – it led to antitrust laws, income taxes on the rich, and greater social protections.

Similarly, New Zealand’s own history shows a pattern of public backlash spurring change. The uproar in the late 1980s and 90s over unaccountable, market-driven politics paved the way for electoral reform (MMP) and a reassertion of social safety nets. Today’s public anger can play a similar role, if it is constructively harnessed. The fact that New Zealanders are now highly attuned to issues of inequality, fairness, and elite influence is, in itself, a positive development. It means voters are looking beyond surface-level politics and questioning who really holds power.

As I have argued previously, some trust deficits reflect a justified scepticism towards unaccountable power structures. In other words, a healthy democracy needs its citizens to be critical of elites – to demand transparency and accountability – rather than placing blind faith in institutions that may be failing in their duties. The current mood of scepticism could be the jolt that New Zealand’s Establishment needs to re-engage with the public and prove it serves the public interest, not just its own interests.

What might that re-engagement look like? Experts and commentators, including those at Edelman, are effectively urging a reorientation of New Zealand’s leadership culture. It starts with transparency – implementing far stronger requirements for openness around lobbying, political donations, and decision-making processes. Reforms like a public searchable registry of lobbying activities, tighter rules for disclosing who funds political parties, have all been suggested as ways to clean up the system. Such measures would make it harder for vested interests to operate in the shadows and could help restore integrity in the eyes of the public.

There is also talk of revisiting stalled legislation to regulate lobbying, an earlier attempt at a lobbying transparency bill failed, but political finance scholars Maria Armoudian and Timothy Kuhner have argued it could be “redesigned and resubmitted if citizens demand it.” The key phrase here is “if citizens demand it” – which is precisely why rising public awareness and frustration is crucial. Without public pressure, politicians have little incentive to reform the very system that elevated them. With pressure, however, even reluctant leaders can be convinced that their legitimacy (and re-election prospects) depend on embracing changes that bolster trust.

Beyond transparency, addressing economic grievances is essential. The data is unambiguous that many New Zealanders feel left behind; thus, policies to reduce inequality will be central to rebuilding trust. This could include revisiting the tax system to ensure the wealthy pay their fair share – a conversation already begun after the IRD’s revelations of the tax paid by the ultra-rich.

Politicians are likely to face louder calls for wealth taxes or capital gains taxes to tackle the perception (and reality) of an unbalanced tax burden. Likewise, tackling the housing affordability crisis, which has locked a generation out of home ownership, would signal that leaders are finally heeding public despair about the future. Edelman’s finding that only 1 in 5 Kiwis think the next generation will be better off should ring in the ears of every MP. To restore hope, bold action on intergenerational issues – from housing to climate resilience to stable jobs – will be needed. Rebuilding trust means delivering results, not just rhetoric.

Crucially, reconciling with the public will also demand a change in tone and mindset from those at the top. The era of “we know best” paternalism is over. In an environment where 67% feel ignored or harmed by those in charge, leaders must show humility and a willingness to listen. That might entail more direct public engagement – from citizens’ assemblies to binding referendums on major issues – to give people a greater sense of agency (recall that 57% of New Zealanders, and even more young people, favour more direct democracy in decision-making).

It also means being honest and transparent about challenges: part of restoring trust is candidly admitting mistakes and failures. As the saying goes, trust arrives on foot but leaves on horseback – it will take time and consistent effort to win back the confidence that has been lost. Every instance of honesty, accountability, and responsiveness can help slowly rebuild the foundation.

At the same time, citizens themselves have a role. The current wave of discontent, if channelled constructively, could reinvigorate civil society. Already we see grassroots movements, community organisers, and independent media trying to hold the powerful to account and present alternative visions. The rise in scepticism towards traditional media (with trust in mainstream media at just 35%) has a double edge: it can fuel conspiracies, but it also pushes people to seek out new sources of information and demand higher standards of journalism. The public’s challenge is to maintain engaged vigilance – to push for change without sliding into nihilism or accepting misinformation.

In many ways, the fact that people are angry is a sign they care; apathy would be a far more dangerous foe. As long as that anger stays tethered to facts and focused on improvement, it can be the lifeblood of a more participatory democracy.

Conclusion: Towards an accountable future

New Zealand’s rising public discontent with “oligarchy” – with a society seen to be run by and for the wealthy and powerful – is a dramatic development, but it should not be viewed only in a negative light. Yes, the collapse in trust is troubling, and yes, the sense of grievance is sky-high. But embedded in these attitudes is a clarion call for structural change and greater accountability. It is a demand that the country live up to its democratic promise. The alternative – a populace that suffers in silence while inequality and cynicism grow – would be far worse.

As I have argued before, a certain amount of scepticism toward elites may be healthy, but it must be met with genuine reforms: re-engage citizens by rebuilding credibility in core democratic institutions or risk a deeper fracture in society. New Zealand in 2025 stands at a crossroads much like other democracies: one path leads toward further alienation, the other toward renewal through reform.

There are signs that politicians are beginning to get the message. In recent years politicians have initiated plans to review lobbying rules, and opposition parties have started talking more about the “squeezed middle” and unfairness in the tax system – rhetoric seemingly lifted from the public’s own complaints. But words will not be enough. Action is the only antidote to mistrust.

As citizens, the onus is on us to keep the pressure on, ensuring that this spike in political awareness does not fade. We should remember that throughout history, periods of popular anger have often precipitated progress – from the extension of voting rights, to anti-corruption laws, to social safety nets – if that energy is directed into the political process constructively. The current moment, turbulent as it is, contains the potential for a more equitable and accountable future.

In the end, trust in institutions is not restored by exhortation; it is earned through justice, fairness, and performance. New Zealanders are effectively telling their leaders that trust will have to be “proven” by deeds, not assumed. The rising scepticism is a public insistence on seeing results: a fairer economy, a transparent government, a media that holds the powerful to account without bias, and business leaders who uphold ethics.

Meeting these expectations will not be easy for the elite – it may require them to relinquish some privilege and embrace oversight – but it is necessary for the long-term health of our democracy. The alternative is a continued slide into grievance and estrangement that serves no one well, not even the wealthy in their gated communities. In the words of an old proverb, “the fish rots from the head” – if our leaders don’t demonstrate integrity, the system fails. Conversely, with genuine leadership and structural change, trust can be rebuilt from the ground up.

New Zealand’s popular discontent today is therefore best seen not as a threat, but as a corrective force. It is a sign of a society waking up and refusing to accept “business as usual” if that means oligarchy. As Bernie Sanders and others around the world remind us, the fight against oligarchy is ultimately a fight for democracy – for a government and economy that serve the many.

That fight is now underway in New Zealand, in town halls, on talkback radio, across social media, and in everyday conversations. It’s messy and fraught, but it signals an engaged citizenry. In raising their voices, New Zealanders are asserting ownership of their democracy. This rising political awareness and demand for change may be just what the country needs to renew its social contract – to ensure New Zealand remains not a playground for the wealthy few, but a society where everyone has a stake and a say. The path forward is clear: heed the calls for reform, address the grievances, and in doing so, begin to restore the trust that is so vital for a healthy, functioning democracy.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of The Integrity Institute

Previous items on this topic of trust:

Bryce Edwards: An age of growing discontent in New Zealand

Bryce Edwards: What’s to blame for the public’s plummeting trust in the media?

Bryce Edwards: Serious populist discontent is bubbling up in New Zealand

Bryce Edwards: New Zealand’s social cohesion is being torn apart

Bryce Edwards: Who does the public trust in 2019?

Bryce Edwards: The Battle for Trust in NZ politics

Bryce Edwards: New Zealand's revolting masses