Table of Contents

Michelle Smith

Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies

Although several of his best-known children’s books were first published in the 1960s, Roald Dahl is among the most popular authors for young people today. The recent decision by publisher Puffin, in conjunction with The Roald Dahl Story Company, to make several hundred revisions to new editions of his novels has been described as censorship by Salman Rushdie and attracted widespread criticism.

The changes, recommended by sensitivity readers, include removing or replacing words describing the appearance of characters, and adding gender-neutral language in places. For instance, Augustus Gloop in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is no longer “fat” but “enormous”. Mrs Twit, from The Twits, has become “beastly” rather than “ugly and beastly”. In Matilda, the protagonist no longer reads the works of Rudyard Kipling but Jane Austen.

While the term “cancel culture” has also been used to describe these editorial changes, there is actually a long history of altering books to meet contemporary expectations of what young people should read.

Should we consider children’s literature on a par with adult literature, where altering the author’s original words is roundly condemned? Or do we accept that children’s fiction should be treated differently because it has a role in inducting them into the contemporary world?

Bowdlerising literature

Thomas Bowdler’s The Family Shakespeare was published in 1807 and contained twenty of the author’s plays. It removed “words and expressions … which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family”, specifically in front of women and children.

“Bowdlerising” has since come to refer to the process of altering literary works on moral grounds, and bowdlerised editions of Shakespeare continued to be used in schools throughout the 20th century.

While Shakespeare’s works were not intended specifically for children, the fiction of Enid Blyton is a more recent example of bowdlerisation of works regarded as classics of children’s literature. There have been several waves of changes made to her books in the past four decades, including to The Faraway Tree and The Famous Five series.

While Blyton’s fiction is often regarded as formulaic and devoid of literary value, attempts to modernise names and remove references to corporal punishment, for example, nevertheless upset adults who were nostalgic for the books and wished to share them with children and grandchildren.

How is children’s literature different?

Children’s literature implicitly shapes the minds of child readers by presenting particular social and cultural values as normal and natural. The term we use for this process within the study of children’s literature is “socialisation”.

People do not view literature for adults as directly forming how they think in this way, even if certain books might be seen as obscene or morally repugnant.

While many people are outraged at the overt censorship of Dahl’s novels, there are several layers of covert censorship that impact on the production of all children’s books.

Children’s authors know that certain content and language will prevent their book from being published. Publishers are aware that controversial topics, such as sex and gender identity, may see books excluded from libraries and school curriculums, or targeted for protest. Librarians and teachers may select, or refuse to select, books because of the potential for complaint, or because of their own political beliefs.

Several of Dahl’s books have previously been the subject of adult attempts to rewrite or ban them. Most notably, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) was partially rewritten by Dahl in 1973 after pressure from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and children’s literature professionals.

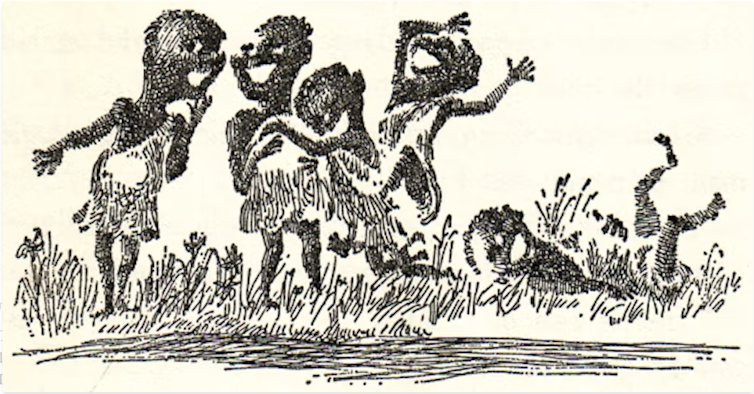

Dahl’s original Oompa Loompas were “a tribe of tiny miniature pygmies” whom Willy Wonka “discovered” and “brought over from Africa” to work in his factory for no payment other than cacao beans.

While Dahl vehemently denied that the novel depicted Black people negatively, he revised the book. The Oompa Loompas then became residents of “Loompaland” with “golden-brown hair” and “rosy-white skin”.

Historical children’s books today

Children’s literature scholar Phil Nel suggests in Was the Cat in the Hat Black? The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature and the Need for Diverse Books that we have three options when deciding how to treat books containing language and ideas that would not appear in titles published today.

First, we can consider these books as “cultural artefacts” with historical significance, but which we discourage children from reading. This option works as a covert form of censorship, given the power adults hold over what books children can access.

Second, we can permit children only to read bowdlerised versions of these books, like those recently issued by Dahl’s publisher. This undermines the principle that literary works are valuable cultural objects, which must remain unchanged. In addition, revising occasional words will usually not shift the values now regarded as outdated in the text, only make it harder to identify and question them.

Third, we can allow children to read any version of a book, original or bowdlerised. This option allows for the possibility of child readers who might resist the book’s intended meaning.

It also enables discussion of topics such as racism and sexism with parents and educators, more easily achieved if the original language remains intact. While Nel favours this approach, he also acknowledges that refusing to alter texts may still be troubling for segments of the readership (for example, Black children reading editions of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn in which the N-word has not been removed).

Dahl’s novel Matilda emphasises the power of books to enrich and transform the lives of children, while also acknowledging their intelligence as readers.

Although many aspects of the fictional past do not accord with the ideal version of the world we might wish to present to children, as adults we can help them to navigate that history, rather than hoping we can rewrite it.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.