Table of Contents

Karl D. Stephan

mercatornet.com

Karl D. Stephan received a B S in Engineering from the California Institute of Technology in 1976. Following a year of graduate study at Cornell, he received a Master of Engineering degree in 1977 and was employed by Motorola, Inc. and Scientific-Atlanta as an RF development engineer.

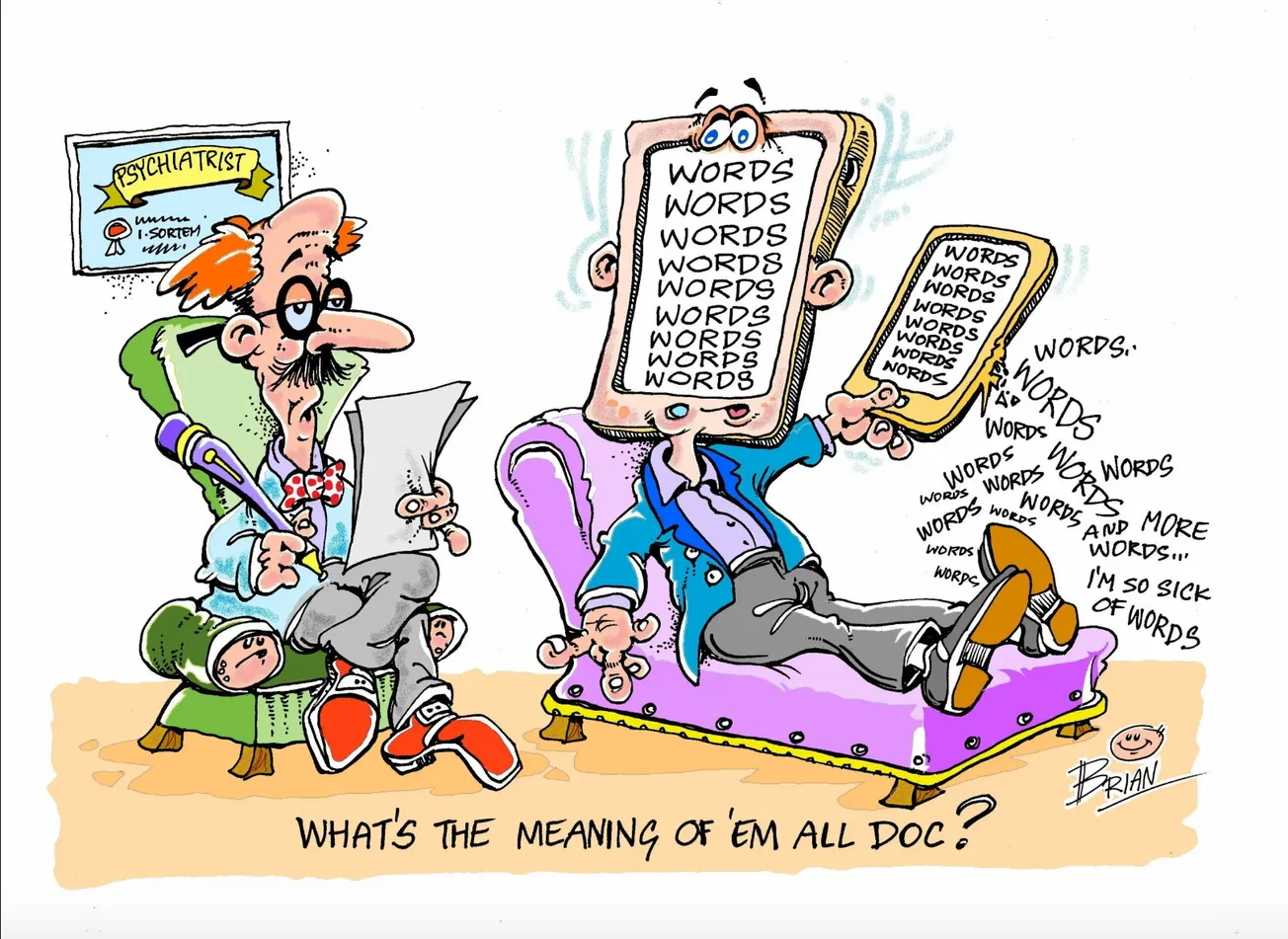

Writing in the Spring 2022 issue of The New Atlantis, British author Kit Wilson wonders if the internet is endangering our mental health by metaphorically burying us in words.

In support of this conclusion, he cites some statistics. For example, a report that the prestigious management-consulting firm McKinsey & Company published in 2012 stated that the average time Americans spent reading or writing each day was between one and two hours from 1900 all the way up to 1990.

But when the internet came along and was joined by text messaging, that number rose to around four to five hours a day – almost a third of a person’s disposable free time (that is, when you’re not doing something like eating or going to the bathroom – and I’m sure some people read while doing those things too).

Information overload

But nobody reads the internet like you would read War and Peace, and therein lies the problem.

He also found a journalist who claims that your average person browsing the internet as part of their daily routine may expose themselves to as many as 490,000 words a day, which approaches the length of Tolstoy’s War and Peace (600,000 words, according to Wikipedia’s “List of Longest Novels”).

Have we exploited digital technology’s amazing ability to multiply words practically without end to flood cyberspace with an ocean of words that threaten to drown us?

My title is something of a conundrum. Being unable to read is what illiteracy means, but what is the measure of reading too much? We have all known the so-called bookworm type who seems to prefer the library to the clubroom or the bar. That isn’t the problem here, because there were bookworms before the internet.

Virtual reality

For his part, Wilson seems to be concerned that as we deal with the world more and more as it is mediated to us in the form of words, we will lose track of what reality is really like and begin to treat it as an abstraction that words adequately describe. The overarching theme of this issue of The New Atlantis is expressed by the somewhat grim cover title “Reality: A Post-Mortem”.

I think it’s a little premature to write reality’s obituary just yet, but I have to admit a general sense of creepiness remains with me after reading it.

The problem we face was captured neatly by C S Lewis in his 1946 sci-fi novel That Hideous Strength, which involves a young sociologist named Mark Studdock who gradually becomes embroiled in some sinister doings as a part of his new job with the National Institute for Coordinated Experiments (N. I. C. E.). Mark was already in a bad way with regard to reality even before he took on his new job. As Lewis points out:

“ … his education had had the curious effect of making things that he read and wrote more real to him than things he saw. Statistics about agricultural labourers were the substance; any real ditcher, ploughman or farmer’s boy was the shadow.”

So the tendency has been with us longer than the internet to take the written word more seriously than the reality that it attempts (always incompletely) to describe. As Lewis shows later in the novel, this habit allows wicked people to do heinous things with the stroke of a pen – after all, the only direct contact a manager might have with the consequences of his order to liquidate thousands of people will be the alteration in some columns of population figures.

Self-control

Having access to more words than ever isn’t all bad. When evil is exposed to the light, it can lead to good people fighting it more effectively. The internet makes keeping secrets much harder, especially if they are secrets about evil things done in public.

I may not be the best person to write about this problem, because whether out of old habits or laziness or something else, I think I am on the low end of Wilson’s estimates of how much time people spend reading stuff on the internet. While I will admit to the occasional lapse of falling down a rabbit hole out of random curiosity, I try to be in charge whenever I’m browsing and attempt to keep my destination in mind. If you know what you want before you go into the store, you’ll probably spend less time (and money) there, and the same thing is true of the internet.

If there’s a specific problem caused by the superabundance of words on the internet, it consists in what it’s done to our reading habits. Back when it took a person half a bottle of ink and an hour to write a three-page letter, the recipient felt obliged at least to read every word and maybe some parts over more than once.

But now that words are so cheap and easily multiplied, we just zip through paragraphs like kids hunting for Easter eggs on the lawn – who needs all this grass? Get to the good part. But what if the good part won’t emerge unless you read the whole thing?

If you’ve done me the good turn to read every word I’ve written down to this point, you have my thanks and appreciation. But you are probably the exception. Nobody can pay that kind of close attention to 490,000 words a day, nor should they.

The best we can do is to be a lot more selective about the stuff we look for and favour sites that are well-curated (the term used to be “edited”) and which allow in only material that is truly worth our attention Because attention is what we bring to the table, or the screen, and, because it’s so limited, we should treat it as the valuable commodity that it is, for our own good and for the good of society as well.

This article has been republished from Engineering Ethics with permission.