Table of Contents

For going on a century and a half, the Ripper murders have exercised a continuous fascination on Western culture. Dozens of movies, hundreds of books and even pop songs have been inspired by the 19th-century serial killer. Not for nothing does the Ripper fictionally declare, in Alan Moore’s From Hell: “One day men will look back and say that I gave birth to the 20th century.”

No doubt, no small part of the fascination is the fact that the identity of the killer has steadfastly eluded detectives, then and now. All manner of suspects have been posited, from a Polish-Jewish barber to a Post-Impressionist painter, from Queen Victoria’s surgeon to the second-in-line to the throne itself. Another recent claim pointed the finger at a Victorian-era female double-murderer. Freemasonry, the Royal Family… the conspiracy theories are never-ending: even Alice in Wonderland author Lewis Carroll has been improbably named as a suspect.

A 2017 book claims that a mysterious “diary” that emerged in 1992, is in fact the real deal: that it is indeed the diary of Jack the Ripper, aka Liverpool cotton merchant, James Maybrick.

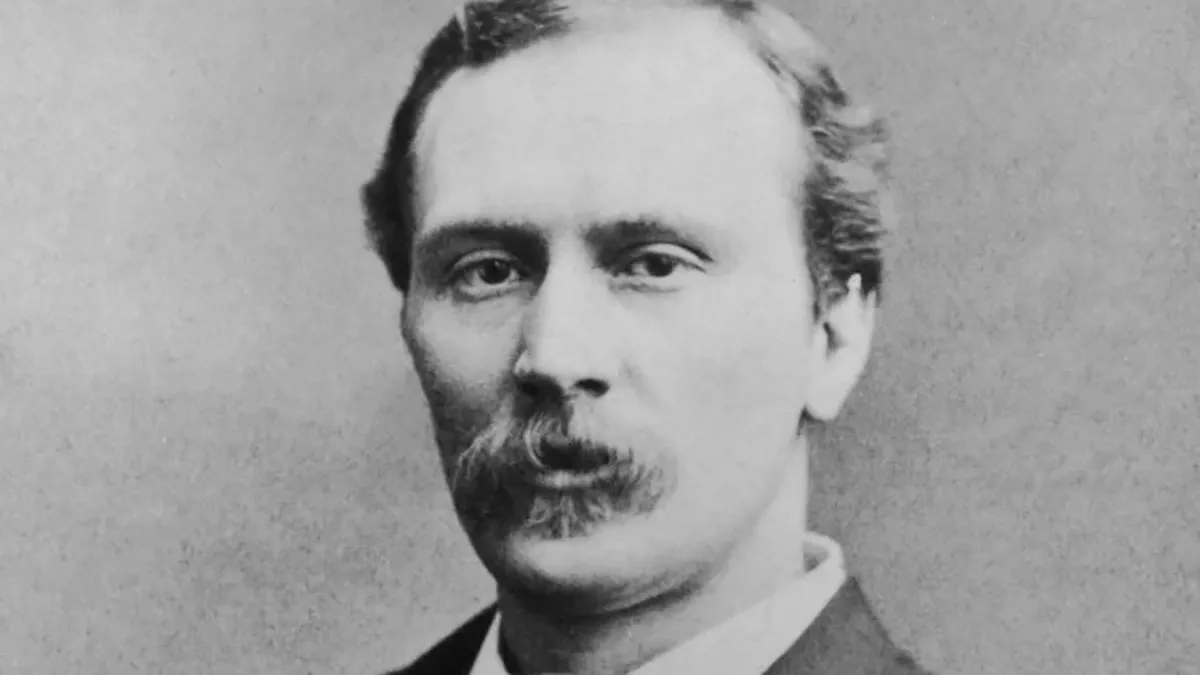

James Maybrick was born in Liverpool in 1838. A successful international cotton merchant, he met a young American woman named Florence Chandler while traveling for work and, although she was 23 years his junior at 18 years old, they married in 1881. The couple had two children, the Liverpool Echo reports.

While little is known about Maybrick’s life, it’s believed that he regularly self-medicated with arsenic and other drugs and that he had an unhappy marriage, with both Maybrick and Florence supposedly engaging in extramarital affairs.

Maybrick suddenly fell ill and died in May 1889 – tantalisingly six months after the last known Ripper murder. At the time, his wife Florence was accused of poisoning her husband. While initially convicted, she was released in 1904.

Fast-forward 88 years.

In 1992, a former scrap metal merchant from Liverpool named Michael Barrett claimed he had found a diary belonging to James Maybrick – and that it provided evidence that Maybrick was Jack the Ripper.

The 9,000-word diary indeed contains clear confessions to the five murders credited to Jack the Ripper, as well as two others. The author signs off with the following words, reports The Telegraph:

“I give my name that all know of me, so history do tell, what love can do to a gentleman born. Yours Truly, Jack The Ripper.”

The diary also reportedly shares details of the killings many experts say only the true murderer could have known. However, the author never reveals his real name, leaving room for the possibility that it didn’t belong to James Maybrick – though certain references in the diary are consistent with details of Maybrick’s life.

According to the diary, the Ripper was spurred to his murderous rampage by catching his wife cheating on him in Whitechapel, the site of the murders. The diary is dated 3 May, 1889, after the murder spree finished and just days before Maybrick’s sudden death.

Less convincingly, some have claimed that one of the few surviving police photographs of a Ripper murder scene, the horrific butchery of Mary Kelly, the Ripper’s final murder, shows the initials “FM” (i.e., Florence Maybrick) written on the walls in blood.

But is the diary genuine?

The question is muddied by Barrett’s differing stories of how he came by it. Publisher and current owner of the diary, Robert Smith, claims that Barrett’s evasiveness is explained by the manner in which he acquired it.

In 2017, Robert Smith’s research claimed to have proven that the diary was actually found in James Maybrick’s former home in Aigburth and that it was written by Maybrick himself in 1889.

Smith, the diary’s publisher and current owner, referred to job timesheets from 1992 to outline how electricians working on the former Maybrick home found the diary underneath the floorboards on March 9, 1992. The workers then gave it to Barrett in hopes that he could sell it to a publisher […]

“I have never been in any doubt that the diary is a genuine document written in 1888 and 1889. The new and indisputable evidence, that on 9th March 1992, the diary was removed from under the floorboards of the room that had been James Maybrick’s bedroom in 1889, and offered later on the very same day to a London literary agent, overrides any other considerations regarding its authenticity. It follows that James Maybrick is its most likely author. Was he Jack the Ripper? He now has to be a prime suspect, but the disputes over the Ripper’s identity may well rage for another century at least.”

All That’s Interesting

What does the scientific evidence say? Extensive testing has ruled out that the diary is a recent forgery. The ink appears to be consistent with the period, and the book is a genuine Victorian scrapbook. The fact that 20 pages were torn from the front of the book might suggest that an old scrapbook was used to perpetrate the fraud and an historical-documents expert claims to have found handwriting inconsistencies.

Adding to the evidence against Maybrick is the 1993 discovery of a gentleman’s pocket-watch bearing mysterious engravings on the inside cover: “J. Maybrick,” “I am Jack,” and the initials of the five victims: Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly.

Electron microscope scans of the engravings found that they indicate a substantial age, “at least several tens of years”. If they were faked, according to Dr Stephen Turgoose of the Corrosion and Protection Centre at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, then they were done so with “considerable skill and scientific awareness”. Another scientist concurred that, “in my opinion it is unlikely that anyone would have sufficient expertise to implant aged, brass particles into the base of the engravings”.

So, for now at least, the identity of Jack the Ripper remains a secret lost to time.