Table of Contents

As I wrote recently, deep-sea mining is fast moving out of the realm of science fiction. While the Deepwater Horizon disaster has put the brakes on undersea oil drilling, oil is far from the only resource to be found in plenty on the ocean floor. Of critical importance in the current geopolitical climate are rare earth minerals.

Rare earths are a group of 15 elements in the periodic table known as the lanthanide series. They are critical in components in many modern technologies, especially batteries. Rare earths are at the core of everything from smart phones to EVs. They are also used in future-facing applications such as robotics and home automation.

Currently, China has a global stranglehold on rare earths. Consequently, other countries, including the US and Australia, are scrambling to develop their own sources. Japan, on the other hand, is scarce in such resources on land – so it’s turning to the sea, instead.

Japan recently launched the world’s first test to extract rare earths from deep-sea mud. The test was apparently a success.

Japan’s government said on Monday that it has successfully retrieved rare-earth-rich seabed mud for the first time from depths of around six km (four miles) during a test mission.

A Japanese scientific drill ship departed on January 12 for the remote Minamitori Island to explore rare-earth-rich mud deposits.

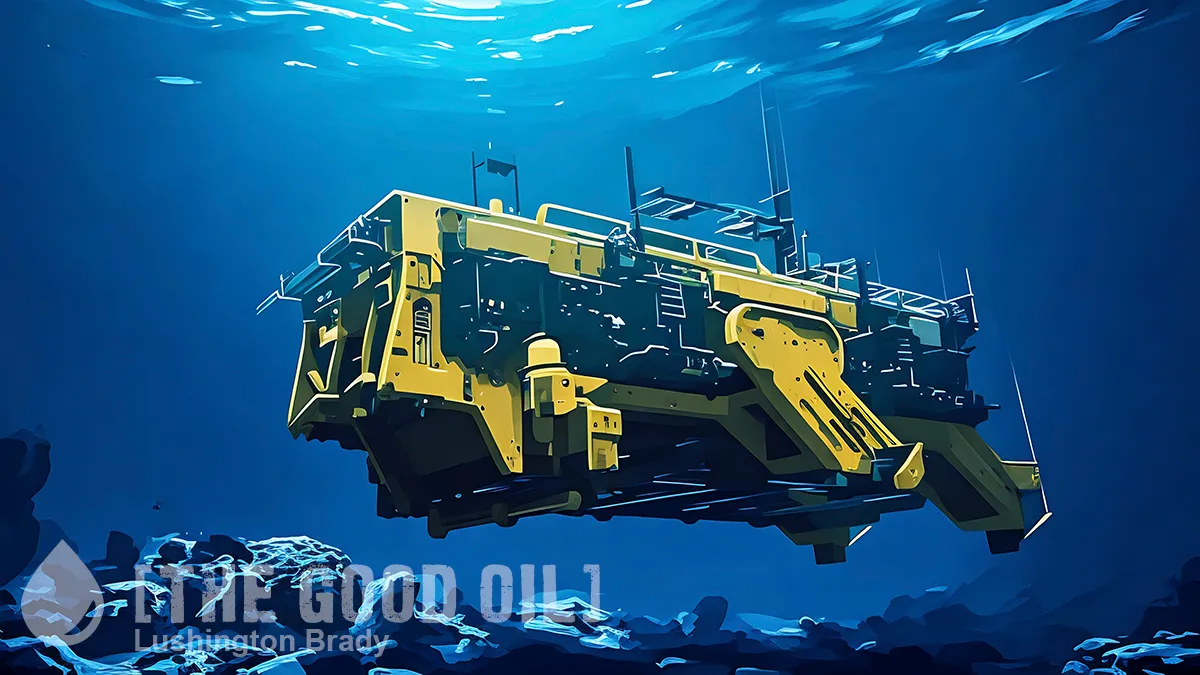

The technology works by remote-controlled robotic vehicles essentially ‘hoovering’ the deep-sea mud, at depths of four to six kilometres below the surface. Other techniques use robotic arms to pick up polymetallic nodules: essentially, lumps of metals-rich rocks lying on the seabed. The material gathered is lifted to the surface, to be processed on the ships operating the robots.

The month-long mission by the test vessel Chikyu near Minamitori Island, about 1,900 km (1,200 miles) southeast of Tokyo, marks the world’s first attempt to continuously lift rare-earth-bearing seabed mud from such depths to a ship.

After arriving at the site on January 17, the vessel began recovery operations on January 30 and confirmed the first successful retrieval of rare-earth mud on February 1, according to the cabinet office’s national platform for innovative ocean development.

Recovery operations had been completed at three locations by Monday, said Ayumi Yoshimatsu, a spokesperson for the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), which operates the vessel.

What, exactly, they’ve hauled up is yet to be precisely determined.

Analysis of the recovered material, including its volume and mineral content, will be conducted after the ship returns to Shimizu port in central Japan on February 15, Yoshimatsu said.

The mud is believed to contain dysprosium and neodymium, used in electric vehicle motor magnets, as well as gadolinium and terbium, which are used in a range of high-tech products.

Japan is not the only nation looking to secure its independence from China for supplies of rare earths. US President Donald Trump is launching a strategic critical-minerals stockpile.

First reported by Bloomberg News, the venture, Project Vault, will combine private funding with a $US10 billion loan from EXIM to acquire and stockpile the minerals for automakers, technology companies and other manufacturers […]

The project has attracted interest from a wide range of American auto and technology companies.

Commodities trading firms Hartree Partners, Traxys North America and Mercuria Energy Group would manage the procurement of raw materials for the stockpile, the official told Reuters.

The stockpile is expected to include both rare earths and critical minerals as well as other strategically important elements that are subject to volatile prices.

Project Vault is intended to help the American auto industry while letting companies keep the risk off their balance sheets, the official said, comparing the logistics of the project to a Costco membership that allows for buying in large volumes.

Another goal is to allow for a 60-day supply of minerals for emergency use, the official said, noting mineral stockpiling is already underway.

And, as an added bonus, this puts even more pressure on a weakening Chinese economy. Beijing has used its dominance of the resources to manipulate prices to its advantage. Losing its control of the global rare earths market will be a strategic and economic blow, following as it does shortly after China’s loss of its Venezuelan oil access, and an explosion at a port in Iran cutting off exports of cheap, embargoed oil from that country to China, its sole buyer.