Table of Contents

You can purchase Nieuw Zeeland An English-Speaking Polynesian Country With A Dutch Name: A Humorous History of New Zealand by Geoffrey Corfield from Amazon today.

Land Ownership In New Zealand

The problems in New Zealand after 1840 between the British and the Maori, were mainly due to two peoples having two completely different ideas about land ownership.

The Maori approach to land is complicated. Land has tribal boundaries and belongs to a tribe unless taken from them. But even lands possessed and not used, or occupied by others, are still considered to be in the original tribe’s possession, and they can demand their rights to it, or payment from it, at any time, even if they don’t live on it, as long as they could enforce it. So displaced tribes always felt that the lands they were displaced from were still theirs. The wars between the Maori had confused everything. Lots of lands were in the possession of one tribe but claimed by another.

There was no ownership of land by individual Maori. Everything was tribally held. So tying down land to who actually had a stake in it, was not only difficult, but almost impossible. Some Maori wanted to sell land to settlers in order to have them living nearby, providing protection for them from enemy Maori, and supplying them with the trade goods they wanted. They expected to be in control over the foreigners and to use them for their own purposes: “You belong to me”. Other Maori of course, did not want to give up land to anybody, Maori or otherwise.

The British on the other hand only recognised the buying and selling of land to individuals or a known ownership group. Land was surveyed, identified by location, and recorded in a land deed related to a plot plan. Ownership was listed on the deed. Everything was black and white. The land on the ground related to the land on the paper. The Maori of course didn’t understand this, they just wanted the goods traded for: “How could I help it when so many muskets and blankets were put before me?” They also didn’t understand it when land was offered for sale but not accepted. It was a collision of two very different ideas of land ownership.

And so you had a complicated and chaotic situation. Surveying could never keep up. Land deals were made by and with the Maori for undetermined areas. Squatters arrived. Settlers arrived. Who represented the Maori? Missionaries bought land for the church, to hold in trust for the Maori, and for themselves. Displaced Maori returned to lands occupied by other Maori. The Maori disagreed amongst themselves. Settlers took what they thought was theirs. All of this was now the responsibility of a new colonial government system that struggled to cope.

There are land policies, land purchases, land sales, land auctions, land taxes, land confiscations, land Acts, land courts, land commissioners, land surveyors, land claims; even genealogical charts are drawn up to help determine Maori tribal land ownership. But land remains the main reason for the British-Maori Wars.

Britain hopes the New Zealand colonies will be self-supporting. They’re not. The New Zealand Company starts four colonies and is involved with two more, and then goes bankrupt in 1847 leaving the British government to take over. It inherits 9,000 colonists, little employment, unsurveyed land, and some poor prospects for agriculture.

Then the New Zealand government goes bankrupt too. By 1853 it has bought 48% of the land area of the country. There is no law and order and another new Governor, trade and farming has stalled, attracting settlers is difficult; and the British-Maori Wars have started (“evil is increasing, the love of many grows cold”). There is trouble everywhere. Well, almost everywhere.

New Plymouth (1841)

Things are relatively quiet at New Plymouth. When The New Zealand Company arrived there were only 55 Maori living there, the rest had either been killed or abandoned the area during the tribal wars. There were no problems buying land. Lots of it (100 square miles), and lots of it was good for agriculture. But the peaceful start didn’t last. When the Maori who had been displaced begin returning, they mix with the settlers, and the Maori who had moved in, and New Plymouth and Taranaki becomes one of the main trouble spots over land during the second round of the British-Maori Wars.

Auckland (1840)

Auckland is relatively quiet too. There are few Maori left living there. But at one time Auckland was a very important place for the Maori, and they fought over it regularly when they had no guns and only themselves to fight with. They levelled off the tops of some 50 volcanic cones and built hilltop fortresses on top of them (One Tree Hill was the largest, once having a population of 4,000).

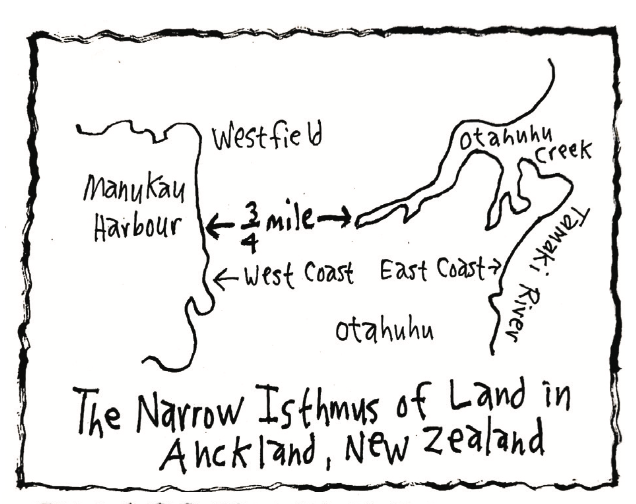

Auckland not only had a fine harbour, but a narrow isthmus of land 3/4 of a mile wide that separates the Northern Peninsula from the rest of the island, and the east coast from the west. Control this land bridge and you control movement up and down the island.

However, when the new small but energetic government of New Zealand moves there, there are few Maori around, and unlike the other towns planned by The New Zealand Company, Auckland had no plan. It just started out with tents and wooden buildings in Albert Park and marked out lots here and there as needed. All the new settlers got 40 acres each. Other than the government people, there were other transplants from The Bay of Islands, Scots from Scotland, Scots from other parts of New Zealand, 90 boys from the Point Puer Boys’ Prison in Tasmania, and discharged soldiers.

You can purchase Nieuw Zeeland An English-Speaking Polynesian Country With A Dutch Name: A Humorous History of New Zealand from Amazon today.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.