Table of Contents

Lawrence W Reed

Lawrence W Reed is FEE’s President Emeritus, Humphreys Family Senior Fellow and Ron Manners Global Ambassador for Liberty, having served for nearly 11 years as FEE’s president (2008-2019). He is author of the 2020 book, Was Jesus a Socialist? as well as Real Heroes: Incredible True Stories of Courage, Character and Conviction and Excuse Me, Professor: Challenging the Myths of Progressivism. Follow on LinkedIn and like his public figure page on Facebook. His website is www.lawrencewreed.com.

Sixty years ago, Beatlemania was rocking the world of music. Writing in the Atlantic, Colin Fleming refers to 1963 as “that magical and formative year for the band”, “the year the Beatles found their voice”, and “the band’s annus mirabilis”. It set the stage for their fabled first visit to America in February 1964.

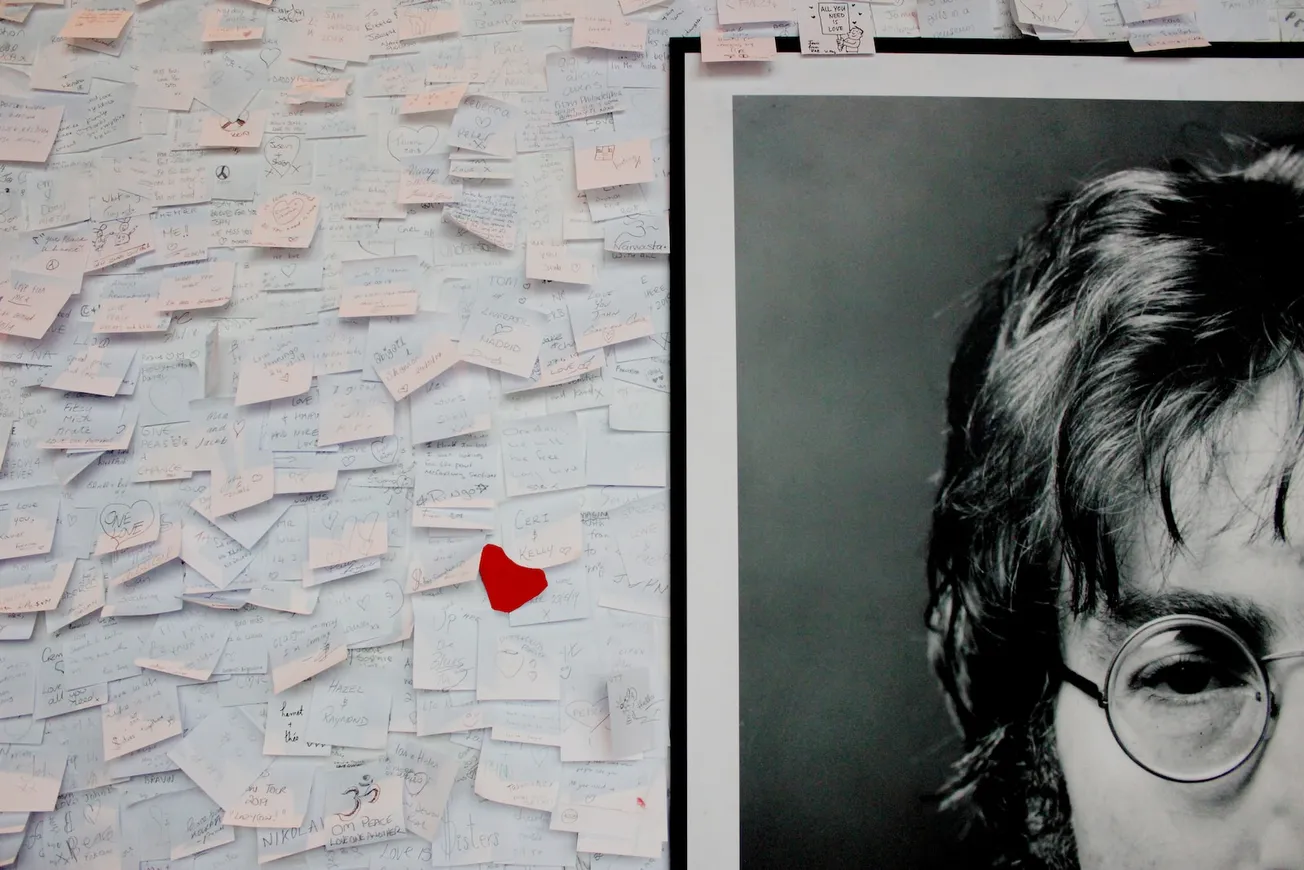

I was 10 years old in 1963 but I well remember black-and-white newscasts of large British audiences screaming adulation at Beatles performances. Particular attention, it seemed, fell upon their founder, co-lead vocalist and guitarist John Lennon. In time, he came to be idolized as a peace activist with a streak of mystical guru in him. His assassination in 1980 canonized him in the minds of all too many.

Stop the John Lennon worship, please. The guy was a fool, a wife beater, a hypocrite, a serial liar, a homewrecker, a drug abuser and an awful father. He even enjoyed making fun of people with disabilities, mocking and bullying them time and again.

As one of the Beatles, he wrote some memorable songs to be sure. But he also wrote (or co-wrote) some of the worst lyrics that ever spilled from a pen.

The tyrant and killer Fidel Castro came to idolize Lennon, which says a lot. In 2000, Castro named a park in Havana, Cuba after him, stuck a shiny bronze statue of the singer in it and sponsored a concert in honour of the man from Liverpool.

In the 42-plus years since Lennon’s death, the glorification continues. Young people are told by oldsters who should know better that Lennon was an icon of peace and love, and that life in the world has somehow never been the same since he was shot in December 1980. Biographies that tell the unvarnished truth about him, such as Albert Goldman’s The Lives of John Lennon, are on the market but instead of reading them, the Lennon worshipers prefer to wallow in the very dream world that the singer often drugged himself into.

Lennon was notorious for abusing his first wife Cynthia. He slapped her hard in the face, in public, multiple times. After years of domestic violence, numerous adulterous relationships with other women and a son (Julian) whom John largely ignored, the six-year marriage dissolved in 1968. Man of peace and love? Count me as a sceptic.

In 1969, Lennon married Japanese multimedia artist and peace advocate Yoko Ono. The pair collaborated on musical and left-wing political causes and later produced a son (Sean). They separated in 1973, allowing John to pursue an 18-month love interest with music executive May Pang. John and Yoko later reconciled.

After his death in 1980, Yoko focused on polishing John’s legacy through her public engagements and musical releases. Domiciled for five decades in New York City, she announced last month (February 2023) at the age of 90 that she was departing the Big Apple for the family’s farm in the Catskills.

One of Yoko’s post-John projects played out in 1990. Its purpose was to note what would have been her late husband’s 50th birthday. It took the form of a synchronous, worldwide broadcast of the popular song she co-wrote with John in 1971, “Imagine”.

The first time the song caught my attention was when it appeared in the final minutes of the 1984 film The Killing Fields, based on the experiences of two journalists, American Sydney Schanberg and Cambodian Dith Pran, during the Khmer Rouge communists’ reign of terror in Cambodia, 1975-79. Upwards of two million people died (roughly a quarter of the country’s population) at the hands of the regime. In the movie, Dith Pran was played by Dr Haing S Ngor, a Cambodian who himself endured torment and torture until his escape in 1979. He won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his portrayal.

Dr Ngor became a personal friend of mine shortly after the movie’s debut. We spent hours together talking about his experiences as well as the film. When he believed it was safe enough for him to visit Cambodia in 1989, for the first time since his escape a decade before, he asked me to accompany him, along with a small group of other friends.

I asked Haing Ngor what he thought of “Imagine” and its role in the movie. He acknowledged the mesmerizing, even haunting, melody but expressed no sympathies for the message of its essentially Marxist lyrics. What John and Yoko asked listeners to “imagine,” Ngor had barely survived to tell the world about. He didn’t have to “imagine” the song’s utopian horror; he personally endured it.

Sadly, the song has suckered millions over the years. Its seductive and devilish allure regularly puts it in the ranks of British favourites. At udiscovermusic.com, Lennon apologist Martin Chilton recently wrote:

John Lennon described the song as “an ad campaign for peace”, and it is no surprise that his moving anthem is such a beacon for those who long for global harmony. “Imagine”, written in March 1971 during the Vietnam War, has become a permanent protest song and a lasting emblem of hope.

Consider the vision that John and Yoko ask us in the song to embrace, starting with “Imagine there’s no Heaven; It’s easy if you try; No Hell below us; Above us only sky.”

In plain language, that suggests we should pretend humanity is just an accident. No Creator, no afterlife, no ultimate justice or accountability, simply the here-and-now and that’s it. That’s been the formula for the worst tyrannies and mass murders in world history, and Khmer Rouge Cambodia was the quintessential example. In urging listeners to imagine neither Heaven nor religion (and therefore no Creator), the song defies what science is increasingly debunking, namely, that everything evolved out of nothing and has neither a beginner or a beginning.

“Imagine all the people living for today,” the song urges. That’s what they do in North Korea today and that’s what life was reduced to under the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Don’t plan for your future because the dictator will plan it for you. In a free society, living as though tomorrow matters is a powerful incentive to live right today. It’s also the reason people save, invest, have children and build homes and lives. But not in the utopia John and Yoko dreamed about.

“Nothing to kill or die for,” the song intones. That’s actually one of the features of Heaven, a place the Lennons imagined away a few lines before. On Earth, I can think of a few things that are often worth killing or dying for: self-defense, saving loved ones, ending or preventing slavery, to name a few.

“Imagine no possessions,” the lyrics urge. Now there’s a winning idea. It’s not yours, even if you worked for it, created it, sacrificed for it, bought it or received it as a gift. It belongs to others, or the fictional “everybody”. This was famously “imagined” by Pol Pot in Cambodia and Mao Zedong in China. This is not some ‘ideal’: it’s a barbarous, Stone Age relic. It’s a prescription for mass impoverishment.

“Living life in peace,” we’re asked to imagine. But how peaceful do you think a society would be if we don’t let people keep their stuff? And how do you make sure they don’t have “possessions” in the first place? By asking them politely not to acquire any? Good luck.

Now you know why the violent despot Fidel Castro had a soft spot in his heart for John Lennon. If Cuban communism is a Disney-like park, “Imagine” is its theme, the counterpart to the annoying “It’s a Small World” that some people can never get out of their heads.

At the end of the dreary dystopian nightmare of “Imagine,” John and Yoko utter, “You may say I’m a dreamer”. That would be a rather charitable statement, given the song’s stupidity. Decent people should want no part of their evil dreams.

This article was reprinted with permission from The American Spectator.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.