Table of Contents

Even thousands of years after they were created, and after centuries of scientific study, the relics of Ancient Egypt are still revealing surprising secrets.

When we look at the elaborate reliefs and paintings decorating Egyptian tombs, its perhaps natural to think of craftsmen painstakingly labouring with delicate precision. Yet, a study of one set of inscriptions shows the thickness of paint periodically thinning and then starting afresh: in other words, an artisan rapidly jotting down hieroglyphs, stopping to dip his brush in a pot of paint, and then carrying on.

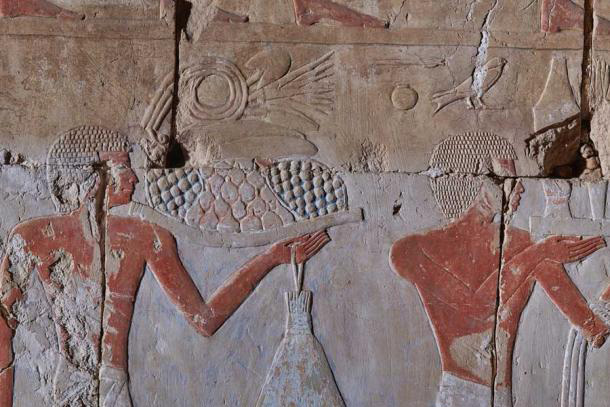

New research on the “Red Chapel” at the Temple of Hatsepshut is shedding light on the working relationship between master and apprentice in Ancient Egypt.

Lead researcher Dr. Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska explains: “The chapel’s soft limestone is a very promising material for study, as it preserves traces of various carving activities, from preparing the wall surface to the master sculptor’s final touches”.

Whereas we are accustomed to praising the genius of the individual artist, the ancient Egyptians made practically no claims of authorship. Egyptian artists worked in communal workshops, which prevented the development of individual styles. Studying the remnant traces of the work of creating the massive relief in the Red Chapel has revealed a seven-step process in operation.

Smoothing the wall and plastering of defects in the stone and joints between blocks.

Division of the wall surface into sections and application of a square grid.

Drawing a preliminary sketch in red paint, copied from a pre-prepared drawing.

Correction of the sketch by a master artist, who also added details in black paint.

Inscribing any text that accompanied the images.

On completion of outlining, sculptors set to work, following the black lines.

Whitewashing and colouring the finished relief.

Similar to the workshops of the Rennaissance Great Masters, apprentices would be set to work on easier sections, like torsos and limbs. More experienced artists worked on details such as faces, and correcting any mistakes on the apprentices’ work. Then both would work on the wigs, allowing the less-experienced to learn from their masters in collaboration.

For example, side-by-side comparison shows that the wig on one figure appears half-finished and rendered with considerably less skill than its neighbour.

Although the reliefs display remarkable homogeneity, indicating that artists worked towards an established style, minor, apparently inadvertent differences occasionally emerge. In another section, hieroglyphic inscriptions near sculpted work perhaps indicates that the sculptors set to work before the full preparatory work had been finished.

Anyone who’s ever worked on a building site can well imagine the shouting match that ensued.

Please share this article so that others can discover The BFD