Table of Contents

Jean Francois Marie de Surville is a French explorer (all French explorers have long names). He is looking for a fabled rich Pacific Island in 1769 (Tahiti), when he goes south from the Solomon Islands, becomes caught in a storm, and decides to try to find Tasman’s squiggly line of Van Diemen’s Land in order to seek food, water and sanctuary for his ships and crew (60 of which have already died from scurvy).

He continues south but instead of finding Tasmania sights the northwest coast of the North Island of New Zealand in the vicinity of Hokianga Harbour (12 December 1769). He goes north around the North Cape and anchors in Doubtless Bay (16 December).

After living peacefully together with the Maori for 14 days (the Maori call the French the “wee- wees” because the most common sound they hear the French make is “oui, oui”), there is trouble between them. The Maori find and keep a small French boat that drifted away. The French want it back. The Maori will not give it back (under the law of “finders-keepers”). The French burn some Maori huts, kidnap a chief, and sail away to South America.

The Maori chief dies three months later of scurvy, and de Surville dies in 1770 when he is drowned attempting to land in Peru in a small boat. (Three anchors from de Surville’s ships are found in Doubtless Bay in 1974 and 1982.)

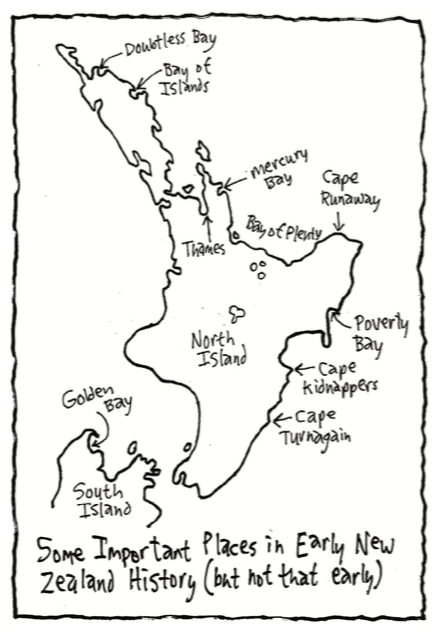

Eight days before de Surville puts into Doubtless Bay, Lieutenant James Cook of the British Royal Navy sails past it 50 miles to the north and names it Doubtless Bay (not knowing if the northern peninsula was a peninsula or an island, he guesses this part of the coast is “Doubtless, a bay”). But Cook had already found Nieu Zeeland himself two months earlier.

The British discover the island of Tahiti in 1767. The British Royal Society (the one for science, not the one that organizes society tea parties with royalty), wants to observe the transit of the planet Venus in 1769, and decides that Tahiti would make a dandy spot to observe it from (one of many). The Royal Navy wants to keep exploring in this part of the Southern Ocean, and so they combine the two expeditions and put Master Seaman James Cook in charge. Cook is promoted to Lieutenant (1768), Commander (1772), and Captain (1775); but he does all his famous discovering of New Zealand and Australia as a Lieutenant. He’s a good navigator, seaman and mapmaker, and he likes science. So he’s the perfect man for the job. The right choice in the right place at the right time. It doesn’t always happen that way. Cook goes on to become one of the most famous people in the history of the world. An incredible story.

Arriving in Tahiti on 13 April 1769, Cook does the scientific experiments, maps the Society Islands, and then on 9 August, following secret instructions and with a Tahitian and his son along as interpreters, he sails south to 40oS latitude (as instructed), turns right and heads west. Cook knows that out there somewhere are a number of incomplete squiggly lines as mapped by the Dutch. One is Australia, one is Tasman’s Van Diemen’s Land, and the closest in the vicinity of 171oE longitude and 42oS latitude is Tasman’s Nieu Zeeland. Because of the Dutch, Cook knows that there is something out there to look for.

He is tacking up and down around the 40oS latitude line looking for land, when on 6 October 1769 seaman Nicholas Young spots it. It’s Young Nick’s Head on the south side of Poverty Bay in the North Island of New Zealand (approximate location 178oE longitude, 39oS latitude). Cook has found the other side of Tasman’s Nieu Zeeland squiggly line of 1642.

Cook goes ashore in New Zealand for the first time on the east side of the Turanganni River in Poverty Bay (now Gisborne), where he sees houses, canoes and people on the west side of the river (7 October 1769). He crosses the river, but the people run away. While the British are looking at the Maori houses however, four Maori attack the men left guarding the boat. The British escape, but one Maori is shot and killed. When the rest of the Maori run away again, Cook goes to look at the body of the dead man. It’s the first meeting of Maori and white turnips for 126 years, but it’s turned out just as violent as the last time.

The next day Cook goes ashore again on the one side of the river, and is met by a hostile crowd on the other side. When the Tahitian talks to them however, they seem to understand, and 20-30 of them swim across the river. The British give them presents, but the Maori try to take their muskets. More Maori cross the river. The situation is getting dangerous again and another Maori is shot and killed and the rest swim back across the river.

Diplomacy is not going well and Cook feels badly about the shootings, but these people cannot be trusted. When trying to talk to them again in their canoes from the ship, they attack the ship and several more are shot and killed and three young Maori boys taken prisoner. The boys seem friendly though and do not want to go back to shore because they say they will be eaten, but they are returned anyway, and Cook leaves Poverty Bay (11 October, “it afforded us no one thing we wanted”).

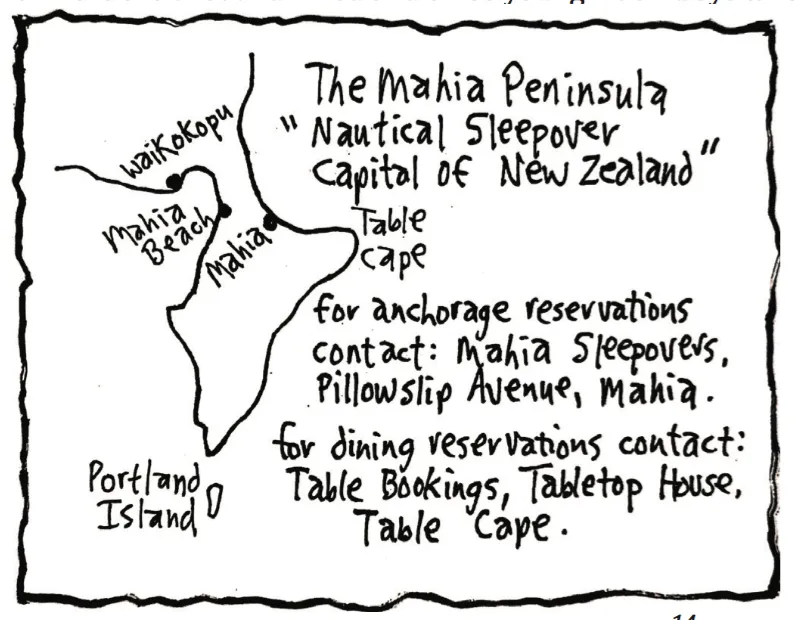

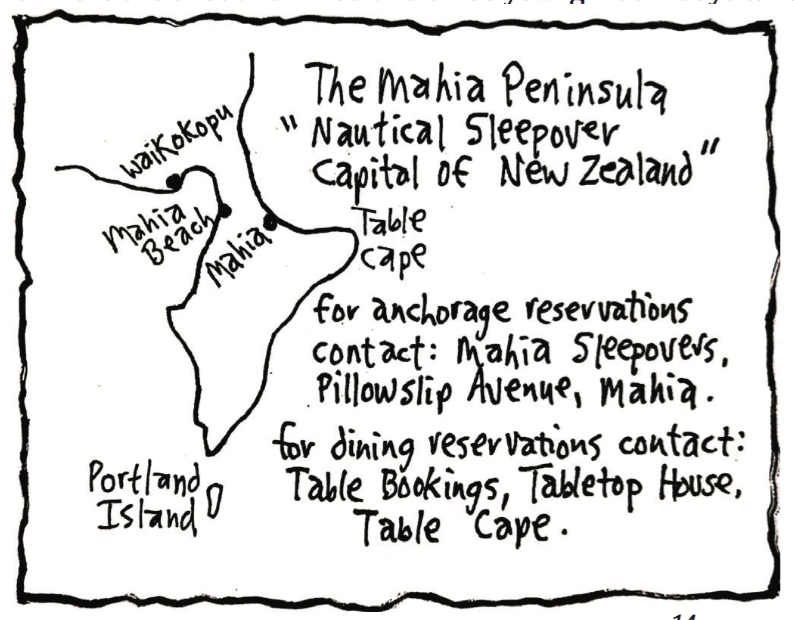

Sailing south, hostile Maori canoes keep coming out at them, but at Table Cape some Maori come aboard peacefully, trade paddles for cloth, and three stay overnight, thus holding the first ever sleepover in New Zealand (12 October 1769).

From Portland Island and around Hawke’s Bay, Cook keeps looking for a harbour with fresh water, but hostile canoes keep coming out and threatening to attack them, so he sails on without landing.

At Cape Kidnappers some Maori paddle out and seem friendly and willing to trade, but then take what’s offered them, give nothing in return, and leave. This doesn’t sit well with the British. When the Maori come back out again they try to kidnap the Tahitian boy, who escapes, and several more Maori are shot and killed. Reaching Cape Turnagain and seeing no potential harbour south on this coast, Cook turns north again (17 October).

Off the Mahia Peninsula five Maori paddle out to his ship, seem friendly and stay for a sleepover, the news of the popularity of the sleepover having spread since Cook was last in this area one week ago (the Mahia Peninsula becomes “The Nautical Sleepover Capital of New Zealand”).

At Gable End Foreland several promising bays are spotted which could offer the possibility of fresh water, and they land first in Tolaga Bay. Here they find water, wood, “scurvy grass”, wild celery, and friendly not so wild people who talk to the Tahitians (the celery is boiled in a pot with portable soup cakes and oatmeal to make “a great Antiscorbutick”). Cook fixes an exact location; climbs hills to look at the country; sketches; trades cloth and nails for fish, sweet potatoes and “curiosities”; and admires the Maori gardens. A little farther up the coast at Anaura Bay they also land and trade for food (19 October).

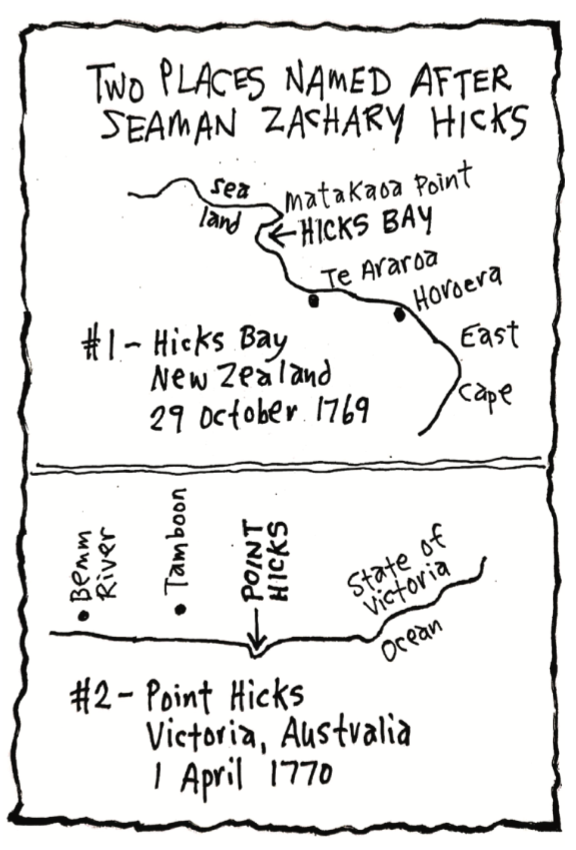

Rounding East Cape Cook guesses (correctly) that this is the most easterly part of this land, and names Hicks Bay after seaman Zachary Hicks, who will later be the first to sight Australia and have Point Hicks, Victoria named after him as well.

If you enjoyed this BFD article please consider sharing it with your friends.

- Chapter One Part one: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter One Part two: A Humorous History of NZ

- Chapter Two Part one: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Two Part two: NZ is Formed

- Chapter Three Part One: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Three Part Two: People Come to NZ

- Chapter Four Part One: The Maori of New Zealand

- Chapter Four Part Two: The Maori of New Zealand

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part One

- The Dutch in NZ: Chapter Five Part Two