Table of Contents

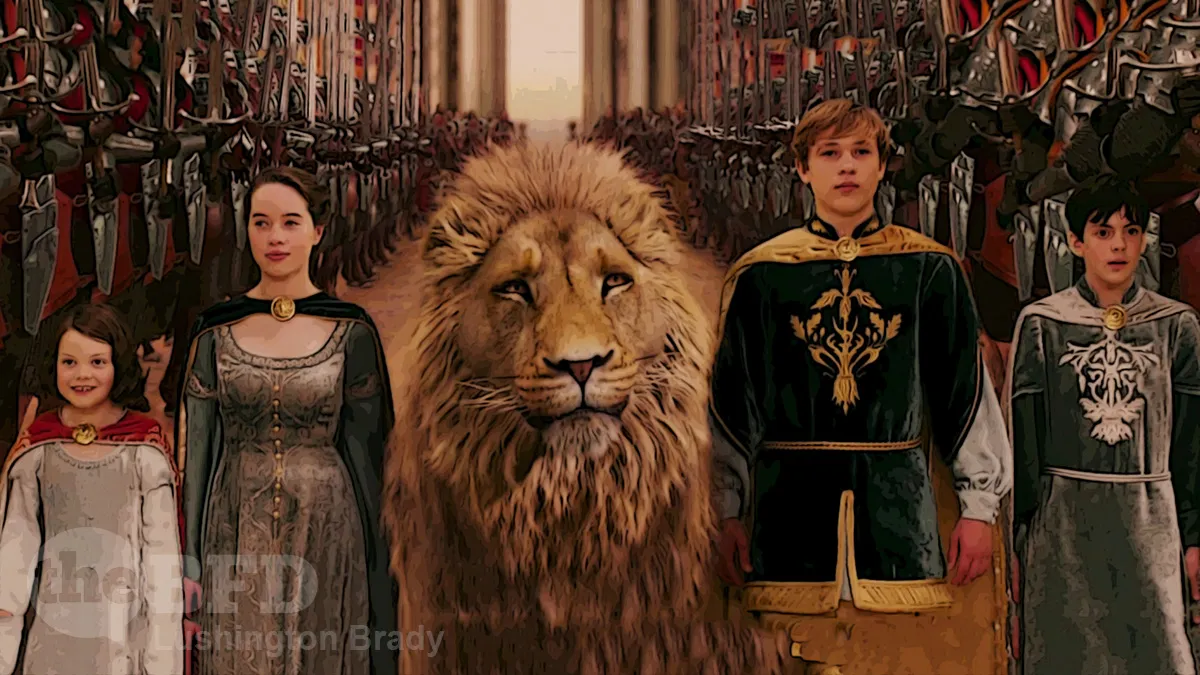

It’s a commonplace that C. S. Lewis’ Narnia stories “are a Christian allegory”. Which, at a cursory glance, most of us assume even as children. Once the penny drops that Aslan is Jesus, it all seems to fall into place. The idea of Narnia-as-allegory has such wide currency that it’s repeated as a given in textbooks and criticism.

But is it true?

The short answer is that it’s not. For any doubters, Lewis himself came straight out and said so.

The Christian allegory argument only enjoys the currency it does because modern readers tend to be less well-educated in what words such as allegory actually mean. Most people, even literary critics, seem to think “allegory” is the same as “metaphor” or “simile”. This simply isn’t true. As Lewis said, in a true allegory, the story is a code and the true meaning of the symbols is the key to unlocking the code. A strict allegory, Lewis said, is like a puzzle with a solution.

Understood in that respect, it becomes obvious that the Narnia-as-allegory claim just can’t hold.

First of all there aren’t really many one-to-one parallels in the book besides the obvious bits about Aslan, which we’ll get to later. Most of the similarities we see are just that: they’re similarities. Peter is kind of like St Peter, and Lucy is kind of like Mary Magdalene, and Susan is kind of like Mary’s sister Martha — but not exactly, and there’s really an important reason for that.

If you read classics of true allegory, like The Pilgrim’s Progress, they don’t read like stories in modern literature.

Instead of rich, well-rounded, realistic characters the characters are usually pretty flat, and they don’t always act realistically, because that’s not their purpose. Their behavior is constrained because it’s tied directly to the object that they represent […]

Another thing about allegories is that the stories themselves aren’t really all that great. I mean sure there’s value in what you’re reading and the lessons learned can be very compelling, but there’s usually not much of a story arc, let alone plot twists and character development, or foreshadowing, or any of the other literary devices that we are so used to reading in our modern stories. That’s because in allegories the main point is to inform not to entertain. The stories take a backseat to the underlying message.

So, if Narnia isn’t an allegory, what is it? Lewis said it’s a “supposal” — which is something much richer and more rewarding.

Lewis asked the question what if there was another world that needed saving. I did not say to myself let us represent Jesus as he really is in our world by a lion in Narnia. I said, let us suppose that there was a land like Narnia, and that the Son of God, as he became a man in our world, became a lion there. And then imagine what would happen.

So, in Narnia, Aslan is not a symbol for Jesus, Aslan is Jesus.

Indeed, as Aslan explains to Lucy in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader:

“In your world I have another name. You must learn to know me by it. That was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia: that by by knowing me here for a little you may know me better there.” And you know, Aslan reveals another secret here: it,s the reason that we readers were brought to Narnia as well. So that we could know these truths the truth better in our world too, and not just know, but really know. our hearts and our minds connect with these stories, in a way that an allegory or a book of systematic theology never could.

When you read Narnia as a supposal instead of an allegory you stop spending your time trying to decipher a code and instead you join in on this incredible, limitless quest to discover the answer to the question What if? And that’s the question that makes all the difference, because, as Lewis explains, there is immense power in great stories.

Lewis, who called himself “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England,” realised that there was a power in stories like Narnia that “could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralyzed much of my own religion in childhood”.

By casting all of these things into an imaginary world stripping them of their stained glass and Sunday school associations one, can make them appear for the first time in their real potency […]

Above all else the Narnian stories were meant to be enjoyed they were meant to transport you into another realm, to take you places you’ve only dreamed of, to introduce you to people you’ll never forget, and to send you on journeys that will leave you forever changed.

Into the Wardrobe

As a literature professor of the 70s noted, if he’d tried to teach his students a course in Christian apologetics, they’d have instantly rebelled. But, teach a course on The Lord of the Rings, (by Lewis’ close literary friend, and, indeed the man who’d converted him to Christianity, Tolkien), and they lapped it up.

As Lewis put it so aptly: Sometimes fairy stories may say best what’s to be said.